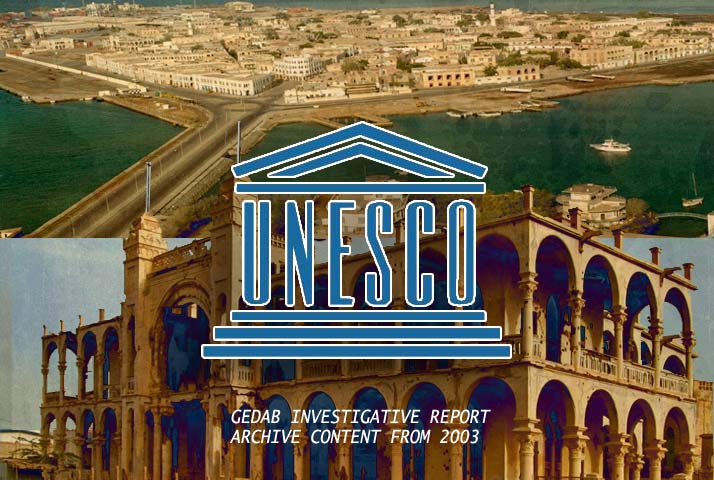

Massawa’s Cultural Heritage: Through the Prism of PFDJ

This investigative report was published on June 23, 2003. Two days ago, Asmara, Eritrea’s capital city was designated a “World Heritage site” for its buildings that were built by Mussolini’s Italian Fascist colonizers less than a century ago, and are affectionately promoted as “Art Deco”. Nothing indigenous about it. The 2003 Gedab investigative report focused on Massawa whose heritage was (and still is) in dire need for attention. The investigative report aimed at creating awareness—it didn’t, particularly with Eritrean intellectuals and friends of Eritrea who we hoped will show some interest. We decided to republish the 2003 report to put the designation of Asmara in perspective.

…with its labyrinthine streets and its hodge-podge of interesting houses, hotels, squares and religious buildings. In the side-streets opposite the harbour you’ll find a 17th-century coral-block house, coral having once been the traditional building material for Massawan abodes, as well as the ancient Ottoman-style houses of Mahmoud Mohammed Nahari and Abu Hamdan. Hidden elsewhere in the precinct are several old covered markets, the 500-year-old Sheikh Hanafi Mosque, with its stuccowork and stunning Murano chandelier, and the visually splendid Campo, a large square lined with houses that boast Turkish and Egyptian wood-carved facades…

The above excerpt describing Massawa, which is derived from lonely planet, is a fitting description that lives in the memory of Massawans. Now with its buildings in serious disrepair, its cultural heritage endangered and a government whose every move is shrouded in secrecy, some Eritreans—particularly the indigenous Massawans—are beginning to question the government’s motives. Is it a case of pro-growth vs pro-conservation? Is it a case of cultural bias? Is it a case of highly centralized decision-making process? This is the scope of Gedab Investigative Report on Massawa’s Endangered Cultural Heritage.

Given the absence of civil liberties in Eritrea and the government’s history of arresting citizens on flimsy suspicions, we hope readers will understand that Gedab’s investigative report of the issue will not include extensive quotes or on-the-record interviews. Via e-mail, Gedab News attempted to speak to government officials to get their side of the story–they did not respond.

The History of Massawa

The historic Adulis or Azzuli as the Semharites call it, was an African gateway to Egypt, Persia, Mesopotamia and Indian civilizations. In the 7th century, after nine hundred years of vitality, Adulis’s civilization, closely linked to Axumite Kingdom, faded. Massawans consider their town, only 30 miles north of Adulis, the rightful heir to its civilization.

Massawa’s island status (the causeway was built by the Egyptians only in the last quarter of the nineteenth century) protected it from the incessant political and military upheavals of the interior, although Hirgigo, which served as the island’s outpost on the mainland, was frequently subjected to attacks by various marauding armies.

Arab rule was established over the Dahlak Islands in the 8th century when the representative of the Ummayads in Jiddah decided to obtain anchorage on both sides of the Red Sea. By the ninth century, an autonomous sultanate had been formed in the Dahlak Islands which extended its sovereignty over Massawa and parts of the coastland. The high level of cultural development of the Dahlaki Sultantate is attested to by the exceptionally beautiful and elaborate Arabic inscriptions in the stylized Kufic ductus which have been found in the Dahlak burial grounds. The sultanate moved its center to Massawa at some point, and some of its cultural and artistic influence remain evident on the island.

Situated as it was at the cross-roads of various civilizations, Massawa flourished—but it was also plunged into conflict and chaos throughout its history. Since 1420, successive Axumite kings, including Isaac, raided and plundered the Massawa region, conquered the traditional rulers, imposed their religious order and levied taxes. Unable to endure the harsh environment, they would leave—only to return and plunder some more. In the mid-16th century, the then Axumite Prince (later Emperor), Lebne Dengel and his Mother Queen, Helena, invited Portugese crusaders to assist in countering the expansion of Muslims on the coast. This clash between Axum and Adulis would culminate in a battle between the Axumite Gelawdios “Atnaf Seged” (Amharic for “The Horizon Leveler”) and Harari Prince Ahmed Ibrahim AlGhazi or Mohammed “Gragn” (Amharic for “The Left Handed”), whose northbound Muslim conquest had expanded to the coastal regions.

Unable to withstand the assault by the Axumite emperors and the Portugese, the coastal area rulers of Massawa, Zeilae, Suakin and Dahlak appealed to the Ottoman rulers in Yemen for protection. In 1557, Ozdemir Pasha, a Mamluk commander in the service of the Ottoman Sultan defeated the Portugese army. He built a garrison in the region and seized control of the island and expanded inland to other parts of modern day Eritrea; southwards to the Ethiopian region of Harrer and westward to Kassala in the Sudan. Massawa was integrated into the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans appointed a local family to serve as their viceroy (Naibs), a status they retained well into the nineteenth century. In 1846, the Ottoman sultan leased control of Massawa and its hinterland to the Egyptians, and in 1865 they were permanently incorporated into the Egyptian Sudan. Ottoman and Egyptian influences blended with the existing architectural and artistic styles of Massawa to give it a distinctive cultural heritage that is at the heart of this report.

By the time the Italians arrived in the late 19th century, Massawa, was a long-established town with a distinct civilization. The city could boast of an architectural heritage that included Missjid Abu Hanafi, built in 1203 by Nu’iman Thabet of Mesopotamia; Misjid Sheikh Mudui, built in 1503 by Hergigo’s Sheikh Mudui; Missjid Hamal, built in 1543 by Sheikh Omar Ibn Sadiq AlAnsari; as well as the equally old Misjid Ghafi, built by Sheikh Ahmed Idris Almasri.

As the only urban center of any significance that can trace its existence before the advent of the Italians, Massawa served as the capital city of the Italian colonial administration until the turn of the twentieth century, when it was relocated to Asmara. The rest of the modern Eritrean cities were built by the Italians around a military network of highways and interests that belonged to the occupational Italian community.

Today Massawa is a city that is fast losing its historical identity. Its merchant community that catered to the needs of the whole population around the area is now non-existent and totally replaced by the PFDJ conglomerate. Most of the houses were either destroyed or damaged during the war of liberation, particularly in 1979 and 1990, when the Ethiopian Derg regime bombarded the city indiscriminately. The Eritrean government has made known its intent to create a commercial enterprise zone, as well as to convert the port into a military base. The complaint is that the pro-growth agenda does not give consideration to Massawa’s unique culture and that reckless measures taken now would be irreversible. Out of this concern, a Diaspora citizens group named the Eritrean Heritage Society (EHS) is stepping in to make the case for protecting Eritrea’s architectural heritage.

Massawa’s Culture & Its Preservation in Post Independent Eritrea

In 1991, Mr. Tageadin AlMoulaye, who is a long time EPLF veteran with a strong personal and professional interest in preserving the historical sites of Massawa, became the first director of the Eritrean National Museum. He was instrumental in reopening the museum and advocating for the preservation and restoration of Eritrea’s heritage. In the mid-1990s, the PFDJ formed the Cultural Heritage Project (CHP). Headed by Dr. Naigzy Gebremedhin, a retired former UN employee, CHP has no clearly defined structure. Although a board was set up to oversee its function, it was not given a clear mandate and support from the government, which has effectively constrained its ability to proceed with its stated projects.

In 1995, for the first time since independence, the government started working with the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO.) That year, UNESCO prepared a “Draft Proclamation for the Protection and Conservation of the Heritage of Eritrea” (Restricted Technical Report, RP/1994-1995/IIA.III; Serial No. FMR/CLT/Ch/95/111). The document was prepared by Mr Richard Crewson and was an effort by UNESCO to assist the Eritrean Government in preparing legislation for the safeguarding of the cultural heritage of Eritrea. The draft legislation attempted to, “reflect and incorporate all the various concerns and proposals” made at a workshop held in Asmara from 20 to 24 March 1995.

On July 1996, Eritrea attended UNESCO’s Second Global Strategy Meeting that was held in Addis Ababa. The themes of the meeting were: African heritage, archaeological heritage, historical heritage, human settlements and living cultures, religious places, places of technical production, etc. Representative from seven African countries (Chad, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, Niger and Uganda) presented reports on major cultural heritage in their respective countries. The Strategy Meeting recommend, among other things, that the World Heritage Convention should take into account a nation’s spiritual and sacred heritage and its physical supports. (Reference Document WHC-96/CONF.201/INF.7.)

By 1999, the task of cultural preservation was diffused among various ministries including the Ministry of Tourism. On February 5, 1999, Ahmed Haj Ali, Minister of Tourism, wrote a letter to Abraha Asfeha, Minister of Public Works, to inform him that, “the Ministry of Tourism has taken the liberty of drafting a sample for a National Heritage Project and Development Board (NHPD),” and asking for comments and feedback before the Ministry proceeded further.

On October 31, 2001, 10 years after independence, Eritrea became the 167th country to sign the Convention Concerning The Protection Of The World Cultural And Natural Heritage. In welcoming Eritrea, Mr. Mounir Bouchenaki, UNESCO’s Assistant Director-General for Culture, stated “this achievement of near universality proved that the world attached special importance to the conservation of natural and cultural heritage.”

The Government’s Decision, Omission

The government of Eritrea has nominated the ancient Quohaito and Mettera as World Heritage Sites, under UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention. From Massawa, Eritrea’s Cultural Heritage Project (CHP) has identified three architectural sites: the Royal Palace Building, the Covered Walkway and the Banco di Roma Building (Bank of Rome). As far as religious buildings are concerned, the Steering Committee of the CHP has listed only two: the Debre-Bizen Monastery,which was built by Abuna Filipos in 1361, and the 200-years-old Kidane Mehret Church in Senafe.

The glaring omissions are striking. None of Massawa’s four grand and old mosques were identified as part of Eritrea’s cultural heritage worthy of restoration. There were no submissions of ruins from the Sahel, Dahlak or even Adulis.

Why is there such imbalance in the recommendations of the government in recognizing Eritrea’s diverse cultural heritage? A recently formed citizens group, Eritrean Heritage Society EritreanHS@yahoo.com, is asking the same question. Based on our research, there are three possible explanations for this discrepancy: (1) the super-centralized decision-making process within the government of Eritrea; (2) Scholarship compromised by politics and lack of diversity and (3) the absence of an influential constituency and lobbying group.

(1) The decision-making process within the government of Eritrea:

When it comes to macro-economic issues and development projects, the cases are managed directly by the President of the State of Eritrea, Mr. Isaias Afwerki. Literally, the president’s office holds the files for all major development projects and, from planning to execution, the president personally manages the entire process. His development project includes turning “Massawa into the Dubai of East Africa,” a tax-free transit and export center. The commercialization of Massawa, which includes development of infrastructure, as well as the tourism/hospitality industry—including restaurants, hotels and casinos—occasionally conflicts with other priorities, such as preservation. When that happens, there is no mechanism for arbitrating competing interests: what the president wants, the president gets.

Unfortunately, implementing the “Massawa into the Dubai of East Africa” dream is a nightmare for some citizens: midnight knocks on the doors and a visit by camouflaged security personnel to arrest dissenters who express unfavorable views about the vision is all too common. In pre-dawn raids, brazen agents of the regime have awakened people in Massawa and ordered them to move to makeshift tents on the other side of the city.

The decision-making process also discourages public servants from engaging in honest debate, weighing the pros and cons of specific issues because they understand the futility of taking advocacy positions contrary to that of the president’s. By all accounts, for example, Mr. Tageadin AlMoulaye was considered a committed public servant who was passionate about the preservation issue. But his service to the nation was met by continuous stonewalling and he has since retired to private life.

Similarly, when Musa Naib was the Mayor of Massawa, he attempted to conform Massawa’s skyline so that the minaret of Massawa’s Grand Mosque would prominently feature even after Massawa’s growth. But in 2000, Isaias Afwerki, overruling the decision of Massawa’s Municipality, personally approved Getachew Bekele’s architectural design for the Twin Towers. In 2000, Eritrea’s Cultural Heritage Project (CHP) was highly critical of the twin towers: in an article entitled “Conserving the Built Environment” and appearing in the “Pearl of the Red Sea” publication to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Massawa’s liberation, CHP wrote:

“the building of the twin towers for the Port Authority located at the edge of the historic old town has changed Massawa’s urban form dramatically. All these changes have taken place almost precipitously, before anyone had a chance to examine critically other alternatives for creating urgently needed new office and residential space.”

The article went on to point out that one of the main purposes of the project is:

“to conserve the unique architectural heritage of Asmara, Massawa and other cities. It will see selective renovations by developing public/private partnerships through ‘custodial assignments,’ conditioned upon the preparation of sensitive restoration plans.”

But the words of the CHP were too little, too late. Almost all “big projects” bear the handiwork of President Isaias Afwerki and nobody else. The issue of converting Massawa into Dubai, much like the earlier (and now abandoned) effort of converting “Dahlak into Monte Carlo” (which contributed to the Eritrea-Yemen skirmish of 1996), has not undergone any debate or serious scrutiny. Although Massawa has a deep-sea harbor, the small number of the berths (only 4) and its limited access due to the conditions of the roads makes the issue of its capacity to accommodate modern cargo ships highly questionable. As many countries in the region have learned, it is ill-advised to rely on centuries-old port facility designed for old technology (dhows and Senbuk) to accommodate current and future capacity (supertankers, cargo and passenger ships.) In 1997, Eritrea’s other port, Assab, was a major beneficiary of the World Bank’s funding for repairing and upgrading its facilities. Yet, the port remains a ghost town and is likely to remain so for as long as the Ethiopian government makes its use conditional on removal of the Eritrean government.

(2) Scholarship Compromised by Politics and Lack of Diversity

Despite Eritrea’s pluralism, Eritrea’s policy formulating elite tends to reflect a uniform political, geographic, religious, political, cultural background. The case of the Steering Committee of Eritrea’s Cultural Heritage Society is reflective of this bias. Chaired by Dr. Naigzy Gebremehdin, it includes the following members:

- Naigzy Gebremehdin, Chairman, Steering Committee on Cultural Heritage

- Eritros Abraham, Office of the President

- Yohannes Tecle Haimanot, Municipality of Asmara

- Alemseged Tesfai, Oral History Project (PFDJ)

- Zemhret Yohannes, PFDJ member in charge of research and cultural affairs

- Azeib Tewelde, Director of the Research and Documentation Center

- Solomon Tsehaye, Cultural Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Education

- Yosef Libsikel, National Museums of Eritrea

- Kidane Solomon, Ministry of Tourism.

- Daniel Tesfalidet, Ministry of Finance

- Kesete Abraha, Steering Committee on Cultural Heritage, Secretariat

The eleven members of Eritrea’s CHP are all PFDJ ideologues. Excepting for one member, all male. Not surprisingly, they tend to view all issues from the same perspective thereby severely limiting discussions and debate, which is a requisite for any type of scholarly endeavor.

To understand how the narrow background and orientation of Eritrea’s policy elite affects all facets of Eritrea, including its history and perception of heritage, consider what Mr. Araya Tessagi, General Director of the Port Authority of Massawa had to say in a publicly available brochure, where he claims that “Massawa is one of the main Port of Eritrea, and was constructed between 1885-1941.” Anyone who visited Massawa can easily tell that the ancient buildings of Massawa certainly were not built in the last one hundred years. So, why the egregious distortions? Is Mr. Araya Tessagi, who presumably lives in Massawa, ignorant of this basic historical fact?

Does the above distortion suggest that some of Eritrea’s occupiers (and their contributions to Eritrea) are prized more than others? Mr. Hailemichael Misgina, a retired UNESCO employee, seems to suggest so. In 1997, at the Conference on Languages held in Asmara, he was interviewed by a South African reporter. The paper states that: “Although the statue of the Ethiopian emperor was determinedly pulled down and Selassie’s palace (both structures at the port city of Massawa) is being left a ‘triumphant’ ruin with gaping holes in its dome and walls, the Italian-style Art Deco buildings of Asmara are conserved with pride – as are some of the trenches and the underground hospitals and other constructions built during and because of the war.”

This goes to the heart of finding a just arbiter of Eritrean legacy, which should be the work of scholars, working independently from the calls of politics. In addition to the uniformity of values, the denial of scholarly rigor is further limited by the PFDJ’s unique prescription of nationalism, which tends to find as much meaning in elevating Eritrean art as it does in denying Ethiopia’s. A case in point is that of Eritrea’s Museum Director, Dr. Yosef Libsekal, an Eritrean who lived all his life in Ethiopia. He went to Paris on scholarship during the Mengistu regime to complete his doctoral studies in the history of Gonder. In 1999, while constructing the Sembel Housing Project, some archaeological ruins were found, and the preliminary findings suggested that they predated those in Axum, Ethiopia. Archeological findings or new theories of that sort are normally published in a scholarly journal first to go through scientific scrutiny. In a “patriotic” fervor, while Eritrea was in a middle of a war with Ethiopia, Dr. Yosef Lebeskal held a press conference to announce that his findings mean that Eritrea’s civilization predates that of Ethiopia, (after all, the region of the Aksumite civilization was primarily modern Eritrea, much more so than even Tigray, let alone modern Ethiopia) thereby shunning scholarship and choosing to be a part of the governments propaganda wars. The results were disastrous. In the May 2000 offensives, when Ethiopia was able to penetrate deep into Eritrea, it rampaged Mettera and Qohaito, some of Eritrea’s most prized archaeological possessions. While the destruction of Mettera and Quohaito is solely the responsibility of the Ethiopian government, Dr. Yosef Libesekal’s provocations were helpful neither to scholarship nor to Mettera and Qohaito.

(3) Absence of an effective Eritrean Lobby Group

The Banco Di Roma in Massawa, built by Mussolini and now housing the National Bank, was slated for demolishing in 1995 to accommodate a planned Housing and Commercial Bank. This proposal faced a strong protest by the Italian Community and worldwide lovers of Art Deco. Consequently, the building was named a cultural heritage and spared and the planned Housing and Commerical Bank was built at Adebabay Square.

While it is true that all Eritreans, unlike some powerful foreign powers, have no mechanism to influence their own government, the case of indigenous Massawans is even more pronounced because a disproportionate percentage of them live in exile and are considered “political enemies” of the Eritrean government. Very few of indigenous Massawans who were exiled have returned, most discouraged by the Eritrean government’s demand for property taxes in arrears for property they abandoned during the Derg occupation era—properties they had neither lived in nor derived revenues from. Consequently, the most articulate defenders of Massawa’s heritage are exiled and marginalized by the government.

Since the 1970s, the demography of Massawa has undergone a major change and, to the majority of its current residents, the old Massawa mosques have no emotional or sentimental value and are no more than old buildings.

Conclusion

Despite the efforts of several concerned citizens and individuals both within and outside the Eritrean Government, no comprehensive list of buildings and sites that could be designated as either “Historic Landmarks,” or part of Eritrea’s “Cultural Heritage” has yet been prepared. In the absence of such a list and a legal framework to protect them, the arbitrary and super-centralized manner of decision-making in Eritrea is leading to a reckless endangerment of the nation’s cultural inheritance.

All fair-minded persons understand that Eritrea’s limited resources must be allocated equitably and fairly to preserve all Eritrean heritage and not just selective locations that promote the PFDJ’s version of history. Yet, due to various reasons—including those cited above–the Eritrean government seems to be following a reckless path in its self-defined role as arbiter of Eritrean heritage. It should be noted that not all the people who are involved in the projects are accomplices of the regime’s recklessness. As a matter of fact, in some cases, it was the very committees appointed by Isaias Afwerki that publicly questioned his wisdom.

The case of Massawa’s heritage is not the only case of the government’s double standards and insensitivity when dealing with delicate issues that are of great importance to Eritreans. The case was chosen for this report because it is one of the most easily demonstrable cases of the government’s recklessness. Eritrea’s history and heritage must not be politicized and the government must find a mechanism to take proactive measures to reach out to citizen groups and Diaspora Eritreans to receive an input that reflects Eritrea’s diversity. This could be a perfectly suitable role for the recently appointed Commissioner of Diaspora Affairs, who can hold public meetings and solicit papers from interested parties. The Commissioner would find a willing and constructive partner in the Eritrean Heritage Society (EHS), a citizen group with the knowledge base and resources to help the government, assuming it has the good will to address this important issue. EHS can be reached at EritreanHS@yahoo.com

[1] Colonia Eritrean: The Regional Commissariat of Massaua to the 1 January 1910. Monography of the Knight Dante Odorizzi, Asmara: Printing office Fioretti and Beltrami, 1911.

Awate Forum