An Open Letter to My Friend

This story revolves around the early memories of my upbringing that shaped my identity. In all conscience, it is neither a riveting story nor based on exaggerated psychological self-assessment of my past; it is just a modest soul-searching endeavour accompanied by some indulgence in retrospection.

Why do I find it important to write about this rather quirky story of my past and my old neighbourhood in this era when dreams are being shattered, lives devastated and souls fractured in Eritrea?

The answer is simple. Weaving my childhood memories into a story does not only help me to contextualise my roots but it also helps me to assess the journey of my adult life. In other words, it is a form of juxtaposition of Eritrea’s past history to its current quandaries via my personal diaries.

What’s more, I find rooting through old relics of my past very therapeutic. But more importantly, this exercise helps me to depict the profile of an old friend with whom we do not see eye to eye anymore over what has become of Eritrea. I can say we were once brothers, but somehow ‘Eritrean Independence’ got between us.

The Maibela Neighbourhood

My childhood memories are formed in Asmara, in general, and the Maibela area, in particular. Life was simple in the old neighbourhood. On the whole, I can say it was the age of innocence. Who would have thought that Eritreans were going to be forced to choose between conformity and exile decades later during the ‘independence’ era?

Our neighbourhood was fenced by Paradiso, the former Aba Mechal Police Station, Ambagagliano, Mr. Sunabara’s SATAE Garage across the Maibela River, and the former Ethiopian Army garrison mostly known as Forto, short form of Forte Baldissera – a fort built on a plateau overlooking the valley of Maibela. Before the City built the Teachers Training Institute and the Stadium in the middle of our neighbourhood, we had the entire area to ourselves.

We, the neighbourhood children, called ourselves ‘deqi-maibela’ (the Maibela Children) as if we owned the polluted river that split Asmara into two. Actually, we hardly knew where the Maibela water rushed after St Joseph’s Catholic Church and Villaggio Genio, let alone understand the role it played in the development of the city. BTW, the Villaggio Genio quarters (Villaggio Indigeno) were lodgings for the local populations built behind the Forto army base. But as far as we were concerned, the Maibela River was ours, notwithstanding the facts.

The river has a long history in the development of Asmara; but as the city population grew by leaps and bounds it turned into a whiffy sewage system. Years later, during the Haregot-Abay mayorship (6os), it was covered by building roads over it throughout the city. And Maibela was no more.

The features that stood out the most of that era were, comparatively speaking, life was less stressful then; family values used to guide and mould our lives; there was coherence and interdependence among community members; the communities took care of themselves and their own affairs; there was enough food to go around; there was no lack of fuel, electricity and water supplies; and there were ample jobs to go around in the private sector.

The Old Gang

Our neighbourhood was at the centre of our world. Aboy Semere was the de facto mayor of our community. Life revolved around his dignified existence and his grocery shop. Families with limited disposable income could use the ‘booklet system’ to buy groceries from his shop – kind of a promissory note to settle amount owed until pay-day. It was all based on trust and kindness – with no interest charged. Basically, the community relied on Aboy Semere for many things.

We, the neighbourhood kids, used to assemble in front of the shop to exchange our daily escapades. Many a times we played football around the shop without proper balls – balls made out of layered old socks. We played hide and seek, banditi (cops and bandits), salvati (tag games) in our backstreets as if there was no tomorrow. We also played marbles until dusk. To this day I wonder why we had to spit-shine them again and again … spit-shining them did not help us a bit to win more games.

Another favourite game of ours was the Akat game (spinning top). We would insert a nail into a sizeable Akat seed (the inner kernel of the Doum Nut) and then set it in motion by briskly pulling a thin rope tightly coiled around the body. The amount of work that went into making the Akat spinning top is literally indescribable.

When bored, we would lie down on the surrounding meadows to watch the clouds pass by; and when in mood we would chase butterflies with tree branches during the sweltering midday sun.

During the rainy season the quick and heavy downpours transformed the nature around our neighbourhood. We would play out in the rain and then wait for the rainbow to spruce up the sky. We had fun; and we thought childhood would never end.

To name a few members that made up the Maibela squad, Ismail, Bereket, Armando, Hans, Fessehaie, Alem, Mohamed , Berhane ChaliQue, Mikiel Forma , my brother Yosief and of course, Asmellash, the quietest of us all.

Ismail was our best footballer, Bereket was the cleverest, Berhane was the funniest and Hans was the story teller. Lucky Hans used to go to the cinema every week; he would then tell us endless stories of Tarzan, Django, Maciste – the Hercules-like figure – and more. It was an era of Westerns, and John Wayne was king. BTW, except in Cinema Roma, most cinemas in Asmara used to show movies in Italian – American movies were dubbed into Italian.

To put it in simple terms, in the end the future caught up with us. As the Eritrean youth were struck by the ‘liberation’ bug, neighbourhoods began to fragment, and the Maibela squad simply dispersed. Years later, we came to realise that the future and that very liberation drive did not hold much for us. Of course, except for Asmellash.

No one thought that Eritrea would create an emotional entanglement in us and become a contradiction in terms. We dreamed big and the dreams simply frittered away after the armed struggle came to an end. Yes, we never imagined that Eritrea would suffer from chronic relapses after liberation. ‘Liberation’ was supposed to help us realise our dreams, and not contribute to a situation worse off than the Haileselassie and Dergue eras.

Eritrea’s affliction manifested itself as the unelected president began to posture as if the country ‘needed’ him more than democracy. It soon became apparent that President Isaias Afwerki could not ‘afford’ to leave the democratic process to elections. He could not leave elections to the ordinary people because he sensed he could be voted out of office. That is why he, together with his abettors, hijacked the outcome of the costly struggle by creating numerous pretexts and contrived contexts. Unfortunately, my friend Asmellash has been there with him all along.

My friend Asmellash Abraha Woldu

Often times I think about the whereabouts of the old gang. Sadly, most of the Maibela kids left the country, some were martyred in the battlefields of Eritrea, one died in a car accident, and I believe the only one still living in Asmara is Asmellash.

Asmellash and I became good friends during our teenage years. Bereket was also close but he did not hang around much with us for he was too busy in his family’s business.

Asmellash was a quiet booklover who was ahead of everyone in every sense of the word. He read and read, and read some more. He loved to read so much he would stay up all night to read serious books while I was still fiddling with lighter reading.

His reading habits started with American comic books. We had plenty of reading material in the city because the American GIs and their dependents would read and discard comic books, magazines, books and newspapers. The local street vendors would collect them from the house boys and girls (employed by the military personnel and their dependents) and sell them to us. Che, a big and tall street vendor, was one of our main suppliers.

Asmellash was hooked on Marvel Comics. Stan Lee was his favourite writer/editor/producer who was best known for the Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, the Incredible Hulk, the Avengers, Daredevil, and the X-Men. He loved them all dearly. His most favourite comic book was ‘Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos’ – an elite special unit that fought missions during WWII. He also read MAD, a brainy humour magazine, which published satire on all aspects of American life and popular culture, politics, entertainment, and public figures. One can say that Asmellash had acquired a good grasp of the Western way of life, particularly American, without leaving Asmara.

In my adult life, whenever my mind strolls down memory lane, it always finds its way back to the old neighbourhood. There I find Asmellash flipping through pages of Boris Karloff’s tales of mystery, Ripleys Believe it or Not, which featured horror stories and odd facts from around the world respectively. Moreover, I see him leafing through Alfred Hitchcock’s stories and images. Alfred Hitchcock was one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of cinema.

I do not remember Asmellash, like many of us, ever exhibiting any nationalist tendencies, or ever dreaming of joining the liberation front; it just happened. He did not dream of becoming a media man during and after the armed struggle; I am sure it just happened. He was so well-read I always thought he was going to embark on a collegiate journey; and as far as I was concerned, he was supposed to produce great literary works. I can say he neither intended nor envisaged of putting himself at the service of the greatest dictator Eritrea has ever seen; I guess that just happened too.

At Comboni College

Asmellash, in the late 60s and early 70s, was a serious student at Comboni College – secondary school setup by Italian Catholics Church. I remember that he was fond of Father Rossi, a frail science teacher whose voice was barely audible. He would mimic Father Rossi playfully while going over lesson plans. He was also fond of Father Menegati, a stocky, energetic English/Geography teacher who rode around the city in his motorbike. Father Menegati ran the school library; and I can say he was the one who instilled the love of the English language into Asmellash.

In secondary school, Asmellash’s friends were Prince, Haile, Ali Bafeghi and some seminarians (fratelli from La Salle). He was not much of a football player but he loved to play volleyball with them. In fact, he was very good at it. Asmellash could nail the ball and at times, he would dare to block Prince’s smashes which were not easily stoppable.

From the school staff who had the most impact on Asmellash was Father Charles, the indomitable head teacher who kept students on their toes. Asmellash looked up to Father Charles. Essentially, the inspiration of the head teacher was what taught Asmellash fine manners, studiousness and diligence. In other words, the Catholic School was crucial in raising him and shaping the qualities and traits of his character.

I am sure, in his solemn moments, Asmellash revisits his youth to have a heartfelt chat with his former mentors at Comboni College. What I am not sure of is whether he is capable to strike up a candid conversation with Father Charles at all. Would Asmellash be able to answer questions regarding the illicit stripping away, closures and seizures of the Catholic Church institutions by the regime?

Asmellash, being a principal constituent of the regime, must have looked the other way when the very institution that taught him decency and the right principles of human conduct was ripped to pieces. I guess it is not wrong when they say that politics makes strange bedfellows.

Every time I see Asmellash on ERI-TV I kind of wince, unable to fathom how we will face each other after Eritrea’s ordeal comes to an end. Will my heart be forgiving enough to welcome him after leading a life of an activist for decades? Will he be forgiving enough to welcome me as an old friend knowing full well I opposed the illegitimate government he served all those years? Will we frankly discuss why many Eritreans have fallen by the wayside while others, the few who usurped power, are frolicking? Will we discuss why many Eritreans are living with their scars and many more are still sailing through their troubles?

Actually I am not too concerned about how we would react towards each other for I realise there is a price to pay for what we do and for what we become in life. Since I am not done with reminiscing about the good old days in the Maibela neighbourhood, let me add a couple of recollections that describe my friend Asmellash.

A Fleeting Glance at Eritrea’s Raging Past

During the Dergue era (military rule) Asmellash travelled to the Soviet Union on an Ethiopian government scholarship. I travelled to Italy to join my mother. A couple of years later I heard that Asmellash had joined the front to take part in the armed struggle. I quite admired him for his courage and that very leap of faith.

The Eritrean armed struggle (1961-1991) was a very brutal conflict. The freedom fighters fought the occupying Ethiopian forces using very daring and gruesome guerrilla warfare such as hit and run ambush tactics, booby traps, and even sending human waves of young fighters at encampments. The armed struggle was so intense it consumed a generation of young lives.

The effect of the armed struggle on Eritrean society was profound. The duration of the punishing struggle, the friction and division between the two antagonistic factions within the same struggle, the unimaginable human and material losses, the relentless displacements of the population and the sacrifices the civilians made to support the cause completely changed the demography, social makeup, attitudes and standpoints within the society. After a generation of Eritreans had given their blood, sweat, and tears to the cause, Eritrea won its independence in May 1991. Independence brought joy and relief to Eritreans in and out of the country. I was relieved to learn that Asmellash had returned safely to Asmara with the victorious freedom fighters.

In early 1992, when I met Asmellash in Asmara, that is after independence, my mind went straight back to the days when we were boys. I noticed the changes in him right away. We did not communicate in the language that we were used to – to ‘jive talk’ in mixed Tigrinya and English. I noticed his conversation was mostly confined to hyping ‘sewra’, the revolution, and how the enemy took a battering in the battlefields. It was implicitly understood the combatants did also take a battering which was not part of the banter.

The first thing that came to mind was silly things such as the A.B.C. Murders – a work of a detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, featuring her characters Hercule Poirot, Arthur Hastings and Chief Inspector Japp. My friend was so fond of Poirot I thought I heard him mimic him by saying “It is the little grey cells, n’est-ce pas, mon ami?” That was all in my imagination; instead, he was mimicking Wuchu’s phrases – full of bluster and bravado. The late Wuchu was a gallant ex-fighter who turned into a notorious general after independence.

No mention was made of books, childhood recollections, or where the country was heading. But my mind refused to let go of the insatiable appetite he used to have for reading and learning.

I was there when Asmellash developed his intellect and transitioned from reading straightforward books to sophisticated ones during the early days. I remember when he put aside the Hardy Boys, Agatha Christie books and started reading bestsellers such as the Anatomy of a Murder (by Robert Traver), Leon Uris’ Exodus, The Day of the Jackal, a thriller by Frederick Forsyth and more. He understood the parable about the seagull in Jonathan Livingston Seagull, written by Richard Bach while I couldn’t make heads or tails of that book.

In the story, Jonathan Livingston Seagull is no ordinary bird; the story models courage in breaking away from the small-minded control freaks and the discovering of the limitless nature of the mind and the spirit. The gull longs to be in control of his own life. I wonder how Asmellash would feel now had he had the opportunity to re-read his favourite book of his teenage years.

Looking back, I can confidently say that Asmellash knew more about the Pentagon Papers and the Watergate scandal than any local journalist in the country at the time. I would like to remind the reader that Asmellash was just a youngster then living in a remote part of Africa. Pentagon Papers dealt with the secret bombings by the US in Indochina; and Watergate was President Nixon’s political scandal that took place from 1972 to 1974, which eventually led to his resignation.

Again, Asmellash could discuss the activities of J. Edgar Hoover, the all too powerful FBI director of the time who was accused of violating civil liberties for the sake of national security and who always exaggerated the threat of communism to suit his disposition.

Frankly, those unique curiosities Asmellash exhibited were mumbo jumbo to me then. He was just a teenager who was keen on exploring the other side of the world. He was even interested in exchanging letters with his American pen pals – an undertaking which was one-off back then. I remember sitting on the stairs that led to his house reading all the replies he had received from his friends. He used to receive more letters than he could handle; then again, it was fun reading them.

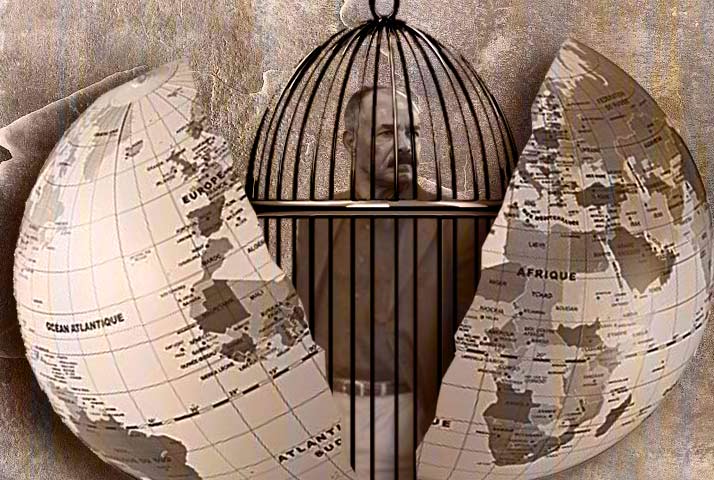

Sometimes I stop and think about those memories just in case they lose their meaning to me as I grow older. However, I cannot understand why I am finding it difficult to put the images of the old and the new Asmellash side by side for the sake of comparison. How can a free-spirited youngster like him embrace a straitjacketed lifestyle in his adult life?

With his practical wisdom, temperance, justice, and the other ethical virtues, I can say that Asmellash was adequately equipped to live a life of thought and discussion; he could have lived a life of a philosopher. I believe his current political life, as the director of ERI-TV, has a major defect, because life within the PFDJ (the government’s party) is a life devoid of contemplation, philosophical understanding and activity.

I have always wanted to ask my friend whether my supposition regarding complicity is right, and whether it applies to all of us. They say: “If you see fraud and do not say fraud, you are a fraud.” The ominous pretence and booming silence will one day come back to haunt us when our lives will be aligned.

Awate Forum