Eritrean Economy: Transportation Crisis And Turf War

A turf war has surfaced and it involves the Eritrean ministry of transportation and the economic arm of the ruling party. The squabble is expected to escalate further. Informants indicated that “a few other ministries are also awakening to the unfettered monopoly of the national economy by the ruling party.”

The ruling People’s Front for Justice and Democracy (PFDJ), the only legal party allowed to operate in Eritrea, owns many companies and monopolizes all sectors of the national economy.

An observer commented, “the frustration is natural because ministers are limited to the role of coordinators between the government and the party’s economic arm with no say on affairs that their ministries should administer.”

It’s possible that the serious transportation crisis that is killing the already crippled Eritrean economy and hurting the people could have triggered the the minister’s sheepish reaction.

Over the last five years, the PFDJ government has boasted about the hundreds of buses it imported from China, and the many new roads that it built, while the state-owned television showed an impressive caravan of buses driving up the escarpments to Asmara. But the transportation crisis continued unabated.

The bright pink, yellow, and blue buses didn’t alleviate the transportation problems that have disrupted trade and travel in the country. But every bus or machinery imported to the country, including Bisha mine equipment, that the state parades in the streets of the capital city as an exhibit of its development efforts, has remained an illusion with no impact on the lives of the people, and didn’t ease the deplorable state of the transportation crisis.

At least one of the bus shipments belonged to the Sudan after it arrived through the Eritrean port of Massawa. The PFDJ paraded the buses in the streets of Asmara seeing them off to their destination in Sudan through the border town of Tessenei.

Queuing PFDJ Style

Long queues of people waiting for a bus in the major bus terminals are too common in the major cities. Capricious station managers whimsically set the bus schedules and assignment them to different destinations, but many people in the countryside still depend on pack animals, or travel long distances on foot. .

Usually waiting for a bus at the terminals extends for many hours, though securing a seat may prove to be difficult even for people traveling a few hours distance to closer destinations. The absence of fixed bus schedules, and their haphazard dispatching , are the source of frustration for travelers .

To avoid standing in waiting under the elements for hours, Eritreans have improvised a convention to keep their turn in queues by putting rocks, cans, and cartons, to secure their places and watch it from a distance.

Oftentimes, the waiting extends to the late hours of the night with no bus provided. The travelers will have to return the next day for the same grueling experience.

Uneven competition by PFDJ owned companies has chocked private transportation companies out of business. Yet, the well-funded ruling party companies that own the buses and trucks have failed to provide efficient transportation services, despite the cheap fuel subsidized fuel they obtain at 40% less than the market price.

The PFDJ companies provide disorganized and corrupt transportation services managed by inept station managers who whimsically dictate bus destinations.

A traveler explained, “we waited for a bus for six-hours and when it finally arrived, the driver refused to go to our town because he insisted he wanted to go to his town in a different location for the night.” He added, “The station manager switched the destination of the bus to appease the driver and he drove the bus to his town with a half empty bus; they told us to return the next day.”

According to travelers, bribing and corruption is rampant in the bus terminals, “the official price of a ticket could be 30 Nakfa but the managers watch it silently while it is being sold for 50 Nakfa by their subordinates.”

The trucking business is not different. In a strange dictate, trucks are not allowed to carry goods worth more than 2500 Nakfa. Violation of that dictate may result in heavy fines, often leading to the confiscation of the loaded goods, mainly food items.”

Such directives are supposedly invented to curb contraband trade and maximize tax revenues. And to remain compliant with the directive, “a truck with a payload of 30 quintals carries only two quintals of sugar, the driver is forced to carry only a fraction of the full capacity.”

Despite all the draconian rules, “a big portion of Eritrean commerce is still rely on contraband goods, including coffee that is smuggled from Ethiopia through Sudan.”

The PFDJ’s Inefficient and ineffective transportation monopoly haa put an extra burden on the economy and it has crippled the entire transportation industry.

The economic arm of the ruling party owns most of the buses and trucks operating in Eritrea.

A Pact of Two Political Lepers

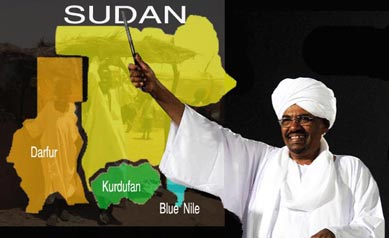

The West has treated Sudan as a pariah state since 1993 when the USA bombed targets in Khartoum. In 2003, in the wake of the Darfur crisis where hundreds of thousands fled their homes while many were massacred by Janjaweed forces supported by the government, the West tightened the trade sanctions against Sudan. Recently, Donald Trump has put Sudan on a six-month review period before considering the easing of the trade sanctions.

In an arrangement that an Eritrean writer described as “a pact of two political lepers”, Sudan uses the Eritrean port of Massawa to import goods camouflaged as Eritrean imports. Eritrea is also under a strict UN sanctions regime, but the sanctions do not include a ban on civilian imports.

Senior Eritrean and Sudanese officials who operate from Eastern Sudan supply most of the contraband fuel, sugar, oils and other edible consumer items to the Eritrean markets. In the last decade, sleepy villages around the border of the two countries have become bustling commercial centers exchanging supplies from the local Sudanese market and imports arriving through the Port of Massawa, a port that receives one ship every now and then. Once the lone ship leaves the berth, the port serves as a mooring berth for the small fishing boats that dock there.

In addition to Massawa, Eritrea has another major port close to the southern mouth of the Red Sea, Assab. However, the port of Assab has become insignificant since the Eritrean-Ethiopian border war of 1998-2000. Until the war erupted, Assab used to handle a big chunk of the Ethiopian import and export trade. However, since the beginning of 2016, Assab has become a closed military region reportedly serving the UAE and Saudi Arabia in their war efforts to defeat the Houthi rebellion in Yemen.

Awate Forum