From Martini to Isaias Afwerki

This is edited and contextualized as a reflective opinion essay inspired by the book “Through the Eyes of a Colonizer” by Renato Paoli and translated by Ruth Tewelde

There is something I keep running into whenever I read colonial-era books, and it never fails to surprise me. It’s the numbers. At the turn of the 19th century, a few thousand Italians ruled over hundreds of thousands of Eritreans. Let that sink in. Two thousand colonizers governing an indigenous population that outnumbered them by orders of magnitude. And this wasn’t unique to Eritrea. A single trading company—the British East India Company—once ruled vast stretches of Asia. India itself was controlled by fewer than a thousand British officers.

How did they pull that off?

This is where my interest in history really lives—not in dates or heroic narratives, but in comparison. History gives us a laboratory. It allows us to place the past next to the present and ask uncomfortable questions. Why do people submit to unjust rule? Why do some systems of domination collapse quickly while others endure? Why does oppression sometimes arrive in uniform and other times in familiar language, under familiar faces?

Dryly put, “Comparative history examines multiple historical cases to identify patterns, similarities, and differences across time and place.”

Fair enough. But my interest is more human than methodological. I want to understand why similar political, economic, and cultural conditions produce radically different outcomes—and why people so often accommodate power even when it works against them.

History, unfortunately, offers a sobering answer: people have always submitted to rule, however unjust or incompetent, when conditions—fear, survival, habit, or fragmentation—make resistance costly. Colonial narratives, especially when written by colonizers themselves, force us to confront that reality head-on. They also have an unsettling tendency to mirror the present.

This essay is a brief comparative reflection on colonial and post-colonial Eritrea. Others can wait.

Reading the Colony Through Italian Eyes

Renato Paoli’s The Colony of Eritrea Through the Eyes of a Colonizer sits somewhere between a travelogue and a political-economic study. It reads easily, but beneath the surface it is heavy with assumptions about race, labor, progress, and entitlement. Paoli was a journalist with broad interests who visited Eritrea in 1906 and traveled extensively across the colony. His observations are detailed, candid, and often revealing—sometimes unintentionally so.

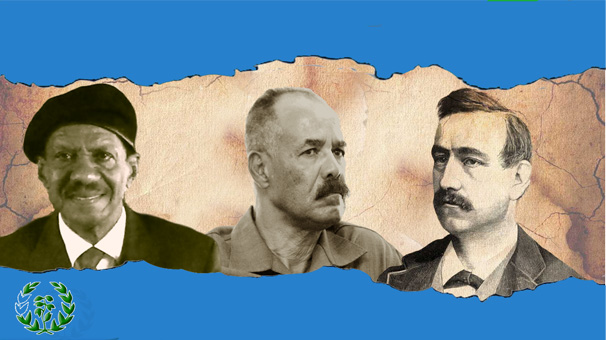

I’ve read many books on Italian colonial Eritrea. The most important, in my view, remains Ferdinando Martini’s Nella Colonia Eritrea: Studi e Viaggi. Martini, who governed Eritrea from 1897 to 1907, was not just an administrator; he was a prolific writer and a committed propagandist for Italy’s colonial project. His works shaped how Eritrea was imagined in Rome and justified what Italy was doing on the ground.

Another key figure is Alberto Pollera, who arrived in Eritrea in 1894 as a volunteer soldier and later became a colonial administrator in Gash-Setit and Seraye. Pollera wrote extensively on Eritrean societies and is often cited as an ethnographer—though always through a colonial lens.

Paoli belongs to this same intellectual ecosystem. His book, available today through Semaikids.com, is a good read if approached critically. Travel writing has a way of pulling you backward through time. As I followed Paoli’s journey from Massawa inland—on foot, on mule—I found myself mentally comparing landscapes, roads, and even the “conscience” of the people he encountered with what exists today.

Order, Obedience, and the Illusion of Stability

Paoli describes a colony that appears stable. Italians move freely. Indigenous people bow when they pass colonizers on the road. There is a sense of order, even legality. But it is the order of domination. Eritreans are subjects, not citizens, and their “respect” is inseparable from their social and economic vulnerability.

Italy itself, it’s worth remembering, was hardly a confident imperial power. It was a newly unified country, stitched together in 1860 by Garibaldi from a patchwork of kingdoms, duchies, and foreign-controlled territories. The Italy that ruled Eritrea was not Rome reborn; it was insecure, eager to prove itself, and often mocked by other European powers.

Paoli, like many colonizers, writes from a position of assumed superiority. He complains when newspapers from Italy arrive late. He waits restlessly for news of ministerial crises and revolutions back home. Meanwhile, he notes with mild amusement that Eritreans do not wear watches—“the sun tells them the time.” He wonders aloud why Africans have no need for such objects, missing the larger question: why should they? Don’t they have the sun?

Then comes the telling line: Why did we go to Africa, if not to teach the natives our material and spiritual needs—and sell them our products?

There it is. Colonization as pedagogy. Exploitation as benevolence.

Colonial Genius, Colonial Cruelty

Colonizers rarely dwell on the lives they disrupt. They focus on comfort, profit, and efficiency. They also possess what can only be called a kind of evil ingenuity.

I once came across a chilling plan described by an Italian colonial writer—possibly Pollera—detailing how settlers could gradually dispossess Eritrean landowners without open violence. The idea was simple: exploit local land laws. Allow settlers to establish residency. Grant them land. Back them with superior resources and colonial authority. Over time, the natives would become landless minorities in their own country. Peaceful. Legal. Effective.

Paoli, for his part, criticizes Italy’s failures rather than its intentions. He laments the slow pace of railway construction, especially the delay in reaching the highlands and Asmara. Railways, he insists, are essential—not for Eritreans, but for settlers and trade. He complains when skilled masons leave for Port Sudan in search of better pay. He envies British and French efficiency in Djibouti and Port Sudan.

Reading this, I found myself nodding—not in agreement, but in recognition.

Paoli’s complaints about Massawa—its lack of port facilities, warehouses, and dry docks—sound eerily contemporary. His insistence that road and rail networks are urgent prerequisites for development could be lifted directly into today’s Eritrean political discourse.

Colonial Critique, Post-Colonial Echo

Here is where the comparison becomes unavoidable.

Today’s ruling party governs Eritrea much like a colony. Self-reliance is preached with religious fervor, even when it becomes an excuse for stagnation. Over twenty-five years ago, the PFDJ promised to rehabilitate the dilapidated railway using “local capacity.” Veterans were brought back. Old machinery was shabbily revived. Modern investment and flexible partnerships were rejected.

The result? A rusting 950 mm gauge track, stretching like the skeleton of a dead snake from Massawa toward the interior. The irony is painful. Even Paoli, writing 120 years ago as a colonizer, was furious about delays. The Italians completed the Massawa–Asmara line in 21 years, despite World War I. The post-liberation state has not matched a fraction of that pace in almost half a century of “independence, peace, and just rule” under the PFDJ.

In 1991, at a conference I attended at Asmara University, an economist, the late Sheikheddin Yassin estimated the cost of rehabilitating the railway at about $1 million per kilometer. He was also involved in the Hergigo power plant project. It is now 2026, and Hergigo power plant operates far below its intended capacity.

This is why Paoli’s book shook me. I wasn’t reading for entertainment. I was reading with comparison in mind.

Martini, Militarism, and the Foundations of Power

Much of Paoli’s work echoes Ferdinando Martini, Italy’s first long-serving governor in Eritrea. Martini established Asmara as the capital, promoted Italian settlement, and aggressively pushed labor extraction. He saw Eritrea as “plentiful land” wasted on people who, in his view, did not know how to use it.

Martini also believed Eritrea should serve as a base for invading Abyssinia. He admired British campaigns against the Mahdist state and blamed Italy’s earlier failures on the lack of a proper colonial base. Under his influence, Eritrean youth were recruited en masse into Italy’s imperial wars—from Somalia to Libya to Ethiopia. The invasion that eventually forced Emperor Haile Selassie into exile did not come out of nowhere; it was carefully incubated.

Martini governed from 1897 to 1907, but his legacy extended far beyond. He shaped Eritrea’s urban centers, extracted manuscripts that now sit in Italian libraries, and laid down a political culture where power flowed downward, never upward.

Final Reflection

Colonialism does not end when the colonizer leaves. Its structures, habits, and logic linger. Sometimes they are inherited. Sometimes they are perfected.

Reading Paoli today is unsettling not because he was cruel—though he was—but because he was familiar.

Awate Forum