Tigray Political Paradox – Preaching Peace and Cultivating Conflict

Created with GIMP

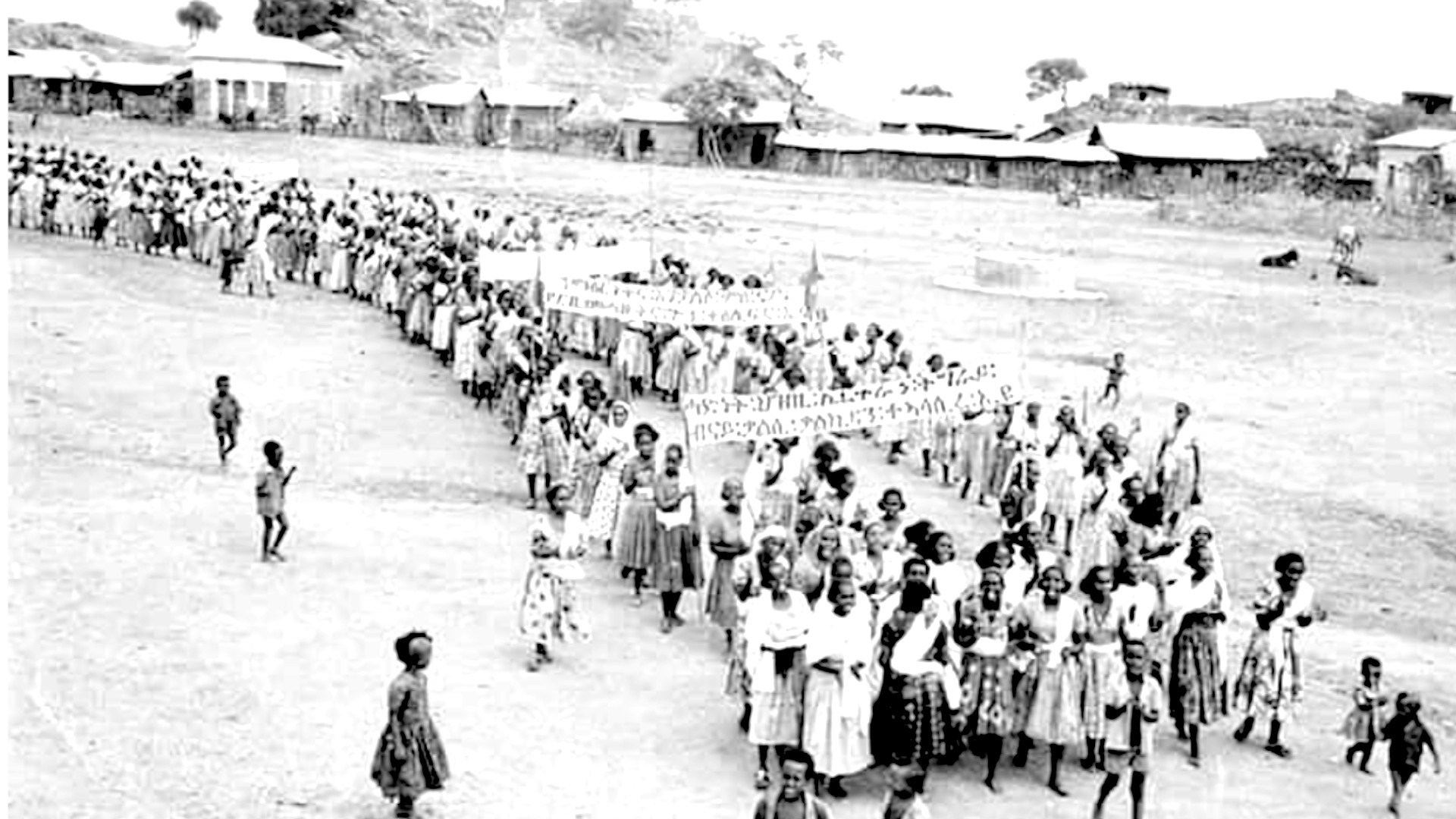

The Eritrean and Tigrayan peoples shared not only a common struggle against Haile Selassie’s and Mengistu’s oppressions, but also linguistic and cultural similarities that could foster trade intensity, cooperation, hospitality, cross-border movements, and socio-economic integration. Case in point, they mutually supported each other and cooperated with each other during some of the most difficult times in history. The statement on the cover picture of this article is a testament to the aforementioned fact. It was taken in 1972 in Shiraro, Tigray. “ሓድነት ህዝቢ ኤርትራን ትግራይን ብናይ ቃልሲ ቃልኪዳን ዝተኣሳሰረ’ዩ”. The rough translation of the text on the poster reads, “The alliance between Eritrean and Tigrayan people is a covenance solidified by common struggle.” There is no recorded historical evidence which suggests that there was ever an ethnic-based conflict between these ethnolinguistic group because neither of them posed existential threats to each other before. However, although both peoples have been endeavoring to coexist in peace and harmony, the Abyssinian warlords from Tigray and now EPLF (PFDJ) and TPLF elites have made peaceful coexistence practically impossible for generations (from 18th— 21st Century). The political elites, however, have been promoting the idea of people-to-people diplomacy as a transnational conflict resolution strategy to solve the problems of their own making. As a supplementary initiative, the transboundary communication, and citizens engagement may play a role in rebuilding and enhancing mutual trust and ease the socio-political and emotional strains of war, but it would be a vain attempt to utilize it as a primary tool to settle and mitigate hostile interstate relations that are not created by the population.

Moreover, while the peoples are hoping the end of the border stalemate would mark the beginning of peace, reconciliation, dialogue and normalization, the emergence of the new extremist political elements in Tigray and diaspora under the banner of Tigray-Tigringi/Agazean may trigger a new resentment and violence that could do irreversible damages. It is because they are entering uncharted waters of ethnic mobilization campaign with islamophobic undertones and toxic political rhetoric that I think can erode the relationship and complicate the situation further.

Clouding the border issue for devious intentions

In June 2018, the Ethiopian government fully accepted the Ethio-Eritrea Boundary Commission (EEBC) which ruled the flashpoint of conflict (Badme) to be awarded to Eritrea. The second step was expected to be taken to vacate and demarcate the border and henceforth the beginning of the normalization of relationships between the two peoples. The Ethiopian constitution clearly outlines that the federal government has a sole political mandate to negotiate and/or sign peace agreements along with exclusive responsibility to enact and enforce defense-related discretions, including withdrawal of troops from foreign lands. As the troops that are occupying the territory belongs to the federal government, Ethiopia’s withdrawal of its army would be a crucial measure towards long-overdue peace. However, PFDJ and TPLF leadership are deflecting from the main issue that sustained the border deadlock each for different reasons. As the border issue has been used as a pretext to tighten Isaias’ totalitarian grip on the population, he has shown no interest in solving it. For the last 20 years, the handover of Badme has been Eritrea’s non-negotiable precondition for dialogue and normalization of relations with Ethiopia, but after Ethiopia’s decision to comply with the agreement, Isaias requested neither handover of the land nor withdrawal of troops from the territory. Be it through deflection or scapegoating others, maintaining the status quo seems to be Isaias’ end goal.

On the other hand, TPLF leadership has fundamentally rejected the agreement on the pretext of ‘dialogue before withdrawal’ as a precondition, which is ultimately offering Isaias the scapegoat he needs. One could argue that the Tigray regional government has neither a constitutional mandate nor legitimacy to negotiate international borders, but it has the capacity to muddy the waters just to feed the political ego. Besides, in their effort to look strong and in charge, the Tigrayan regional government is falling for Isaias’s and Abiy’s strap in so many ways. For instance, Abiy Ahmed through his politically appointed director of ARRA, Kebede Chane, is closing the Hitsats refugee camp in Tigray where many vulnerable Eritrean refugees have been hosted.[1] Reports indicate that the move was initiated at the requisition of Isaias Afwerki, but the silence of the Tigrayan regional government has given the Eritrean public the impression that the decision has been initiated and implemented by Tigrayans which is cropping up some resentments among Eritreans.

When it comes to Badme, it is an arid land with no economic or sentimental values to it, but it is increasingly becoming TPLF’s symbol of dominance. There was no ambiguity that the Algiers Agreement was Final and Binding. And the Boundary Commission rendered its decision ruling that Badme falls under the sovereignty of Eritrea. However, contrary to peace-fostering-principles, Tigray has actively been involved in building houses on the disputed territory in question in defiance of the international ruling, which clearly gives the impression that there is an absence of genuine and practical desire to solve the border dispute with Eritrea. Opting for endless stalemate is clearly not a tactical brilliance, but an ego-driven illusion with no consensual pathway to peace and no conceivable positive outcome.

The second element which is largely the focus of this article is the Tigray-Tigrigni movements. Tolerated and probably promoted by TPLF leadership, this group does not incline towards negotiations, but categorically downplays the relevance of artificial boundaries. A border is what makes a state. It is a geographical representation of national existence which is at the heart of international peace, law, and order. If there is no border, there is no state. In the contemporary world, only the Islamic State intends to create a state that does not recognize international borders and state sovereignty by dismissing it as ‘man-made rules that separate Muslims from each other.’ Yet, the Islamic expansionists aspire to invade and occupy contiguous foreign territories with reference to medieval history to secure transnational religious homogeneity and religious identity. In the same manner, the Tigrayan entities are expressing their sense of entitlement to lands across their border on the grounds of ethnic, cultural, and religious homogeneity with the Eritrean Tigrigna speaking ethnic group.

Undoing colonial boundaries to indulge a hypothetical imperative of the exiguous?

There is no question that colonial boundaries have arbitrarily divided related ethnic groups across the continent. For instance, the Nuer ethnic group is split between Ethiopia and South Sudan, the Afar ethnic group amongst Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti, the Kakwa between Ugandan and Sudan, the Masai between Kenya, and Tanzania, the Lou between Kenya and Uganda, the Hausa amongst Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria. However, despite their historically problematic origins , it is undeniable that colonial boundaries are the bedrock of contemporary African countries, including Ethiopia. Ethiopia borders with six countries in the sub-region with an evident presence of inter-ethnics in each country and each of which acknowledges, respects, and protects their borders. They tend to abide by them and have no intention of going back to precolonial era. There is widespread agreement that the contemporary African boundaries were drawn without respect for social and ethno-linguistic groupings of its inhabitants. However, regardless of the arbitrary and imperfect nature of the African boundaries, African countries are aware that maintaining colonial boundaries is less costly than continental reshuffle for the hypothetical benefits of ethno-linguistic homogeneity. African States’ acceptance of the territorial status quo and the inviolability of the colonial boundaries was formally and explicitly proclaimed by the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in its 1964 Cairo Resolution.[2]The relevance of colonial boundaries cannot be denied, nor can it be removed for the convenience of extremist political elements, but it is possible to reduce its negative effects by creating a sensible, peaceful and integrated socio-economic policies that benefit the stakeholders. Establishing a sustainable peace would require constructive, realistic, and conciliatory approaches and compatible goals that go beyond the argument of transnational ethnic homogeneity.

The colonial boundaries may split the borderland communities into two or more countries, but it should not affect their socio-economic livelihoods and civic bonds. For instance, the western Eritrean lowland has been inhabited by nomadic communities belonging to the Beja ethnic groups (Beni-Amer and Hidareb) but they were split between Eritrea and Sudan. Be that as it may, they have maintained a peaceful coexistence with a perpetual cross-border interplay of pastoral nomadism, marriage, migratory movements, and agro-pastoral seasonal migrations. Consequently, many members of these inter-ethnic groups hold dual citizenship-Eritrean and Sudanese.

But the Tigray-Tigrigni’s strategy is to pretend to be interested in solving the border problem by denying its existence. A reasonable entity(ties) could not/should not dismiss a border war that claimed 100,000 lives, displaced millions and heightened the resentment between the co-ethnics unless they want to reignite a war. The only way forward is to resolve the border dispute and start reconciliation and the normalization process where the two peoples can enjoy peace, development, and a state of normalcy.

Devil in disguise: arrogance and naivete masked by ethnic fraternity (የሕዋት ኢና)

If handled with care, I believe the presence of commonalities of ethnicity, kinship, language, religion, and culture between related ethnic groups at borders may facilitate the possibility of communal cooperation and socio-economic integration. It is important, however, to avoid a simplistic view of colonial artificial boundaries. It has not only divided the same ethnic groups across Africa, but it has also created an environment for ethnic groups to grow apart and construct their own socio-political identities which have obscured kinship and ethnic affiliations across borders. For instance, the artificial boundary coupled with generations of foreign dominance, colonization, and war has pushed Eritrean Tigrigna ethnic group towards Eritreanization. The Eritrean Tigrigna ethnic group have maintained some cultural similarities with the Tigrayan ones, yet they are a distinct ethnic group with different nationality and socially constructed differences that hardly identify themselves with their kin in Ethiopia.

And there is no evidence to suggest that inter-ethnic similarities or differences alone guarantee peaceful coexistence and integration, nor does it cause an outbreak of violence and tension. There is no positive or negative correlation between ethnic similarities and peaceful coexistence. It is worth noting that Hutu and Tutsi of Rwanda are culturally identical who share the same language, beliefs, and customs. The same applies to the Somalis population. In fact, ethnicity has not been the cause of conflict per se. It is the action or inaction of political elites and/or ethnic entrepreneurs that often cause conflict. As political elites and ethnic entrepreneurs attempt to mobilize their ethnic groups or clans in order to gain or maintain certain political privileges, power, and resources at the expenses of other ethnic groups, they often play negative roles in polarizing societies, escalating fear, grievances, ethnic rivalry, competition, and tensions posing threats to the survival of others. Under these circumstances, it would not come as a surprise if the threatened ethnic groups respond with violence to maintain their status, assure their existence and security. Therefore, establishing and maintaining inter-ethnic harmony would require acknowledging, understating, and respecting the other party’s position, interests, internalized perceptions, attitudes, and choices. An effort to evaluate and understand things from the other’s perspective would ultimately be fundamental steps to avoid ethnic-related tensions.

In their attempt to exploit and control African societies, colonialists were known for creating one dominant ethnic over the other, disregarding the presence or preferences of other inhabitants. Consequently, the self-serving, exploitative, and shortsighted colonial legacy has been the cause of most socio-economic, political, and inter/intra ethnic tensions across Africa. Similarly, the Tigray’s extremist elites are using the self-determination rights in the ethno-federal system in Ethiopia to depart from the Amhara dominance, but they are misusing the very concept to delegitimize a sovereign neighboring country and exert its ethnic dominance over minority ethnic groups. Tigray is a region in Ethiopia and the Tegaru is the people who inhabit the region. The Tigrigna speaking group in Eritrea is named after its language, not after its region. They refer themselves as Tigrigna ethnic group, and hence outsiders should address them as such. The Tigray-Tigrigni movement, however, is relabeling the Eritrean Tigrigna ethnic group as ‘Nay Semein Tegaru’(Northern Tigrayans).

If any Eritrean ethnic group was ever to be renamed, it is up to the indigenous and bona fide citizens of the country. One must understand that it is politically, legally, and morally unacceptable to rebrand something you do not own or have control over. However, by rebranding the Eritrean ethnic group, they are knowingly or unknowingly conveying a message of superiority and dominance over the other. In an effort to revive the 1970s TPLF manifesto[3], the Tigray-Tigrigni movement seems to be dead-set on dismissing the Eritrean Tigrigna ethnic group and renaming them as Tegaru’, which delegitimizes their current status. They are not doing it just because they aspire to belong to an Eritrean Tigrigna group but to have access and control over their resources including a sea outlet. However, the claim of ethnic fraternity to misappropriate someone’s political identity and violate the international norms of territorial integrity and state sovereignty to lay claim to the land and sea is convenient ammunition for conflict. Eritreans are vocal about this, but because they have other pressing priorities at home, the magnitude of outrage is still simmering underneath. Be that as it may, their silence should never be confused for consent.

Eritrea is not Tigray

Eritrea is a country with multilingual, multicultural and multifaith ethnic groups who paid blood, sweat, and lives to achieve their independence. Therefore, it would be in the fundamental interest of Tigray region or state to accept, respect and acknowledge the presence of multifaith and heterogeneous ethnic groups who inhabit the Eritrean land and the sea. Doing so would also facilitate the establishment of a neighborly partnership that is based on mutual trust, respect, cooperation, peaceful coexistence, and development. Unfortunately, the Tigray-Tigrigni movements keep depicting Eritrea as the land of Tigrigna speaking Christians. The Tigrignazation of Eritrea maybe the revival of the 1970s TPLF manifesto, but the islamophobic tendency is inheritance of the Abyssinia legacy where monarchs legitimized the externalization of Islam and the suppression of religious and cultural practices of the oppressed, and enforced the subjugation, persecution, socio-economic alienation and forceful conversion of Muslims into Christianity all in the quest of religious and cultural uniformity[4].

Therefore, the growing tendency of cultural and religious homogenization of Eritrea in pursuit of Abyssinia’s historical and political narratives is counterproductive at best, and dangerous at worst. The main objective is to expand the borders of Tigray deep into Eritrea. To that end, they are redefining every Tigrigna speaker as a citizen of Tigray. However, if they are willing to give themselves an opportunity to listen and learn about the contemporary Eritrean society, they would find out that even Eritrean Tigrignas are not internally homogeneous. The Tigrigna ethnic group largely lives in the three highland regions (Hamasien, Seraye and Akeleguzay). Each of them has different customary legal systems, beliefs, traditions, institutions, perceptions(their perception of others) and identification(how they identify themselves).

The overly simplistic and reductionist approach of the homogenization campaign is being done with utmost arrogance, naivete, and an overwhelming presumption that a Tigrigna Christian will permanently remain in power in Eritrea. With the current campaign of planting seeds of hate, prejudice, ethnocentrism, and islamophobia, there is a high probability for tension when a non-Christian or non-Tigrigna Eritrean comes to power. More importantly, whether a Christian or a Muslim comes to power the outcome is most likely the same. It is a common practice for politicians to do what they think will get them elected. And no politician can obtain or maintain power by sympathizing with foreign extremist elements that demonize Muslims and other eight recognized ethnic groups in the country, because xenophobia and inter-ethnic hatred are threats to national unity and security. Therefore, national leaders will be required to take security measures commensurate with the magnitude of the threat it poses.

The quest for de facto statehood by delegitimizing a sovereign and independent country

Most political and civic movements in the Tigray region including Tigray Democratic Movement, Salsay Woyane, National Congress of Great Tigray, Seb Hidri Civic Society of Tigray and the Agazian are advocating for secession of Tigray with a common tendency towards territorial expansion and ethnic homogenization of Tigrigna speaking people. The latter, however, is the most toxic political movement with islamophobic grandiloquence. Eritreans understand the pressure the Tigrayans are under to declare a de facto statehood, and why they are throwing everything at the wall to see if it sticks. Eritreans are keenly observing how Tigrayans are displaying military bravados and trying to invest heavily in the symbolic paraphernalia of statehood in an effort to show strength and capacity. They understand the challenges and hence sympathize with their cause. As the parent state (Ethiopia) has a de jure claim to the Tigrayan territories, Tigray will face an uphill battle for international and regional legitimacy. It will certainly be harder to attempt it without a patron state and ally. However, the de facto statehood aspirants of the Tigray-Tigrigni movements are not seeking a strategic ally. They are claiming ownership of the ally, its history, sacrifice, patriotism, and symbols. Eritrean history and patriotism have been subjected to attacks by those who want to diminish it. Here is how the sardonicism goes: “Eritrea is a fake country created by colonialism; we have to trace our commonality back to the precolonial era to create real country (as far as Axumite kingdom)…” They approach it as if Eritrean cultural and political identities have been in a constant state of stagnation since the Axumite Kingdom. They want to resume a borderless relationship with Eritrea from where they left off more than 1,000 years ago. Ethnic identity is not a static natural souvenir, but a socially constructed phenomenon prone to change over time. There is a large body of literature that demonstrates that individual ethnicities have been in a constant state of change in Africa, which has been influenced and shaped by a series of historical events including African and European colonialization. Therefore, the existing evidence suggests that ethnic groups are dynamic rather than static. The Eritrean Tigrigna ethnic group is no exception.

Although the Tigrigna ethnic group and Tegaru have maintained contact and a relatively peaceful relationship, the aggression of Ethiopian and Tigrayan warlords may have pushed the ethnic group further apart in terms of negatively influencing the perception of one against the other. Furthermore, the division and mistrust between the two were further shaped by a series of historical phenomena and injustice. The cultural divergence goes back to the 14th century when Eritreans began writing their own customary laws that reflected the heterogeneity of customs, beliefs, norms, values, and laws of the Eritrean people. It could also be argued that further psycho-social, economic, and political divergence had also occurred which were largely influenced by the colonial experience and the post-colonial struggle for Eritrean independence.

Driven by hatred for Isaias and his PFDJ political party, few Eritrean Tigrignas in the diaspora have also been expressing a desire to belong to this precarious and mischievous inter-ethnic political experiment. The extended oppression, cruelty, and exploitation in Eritrea has evidently shaken the basic fabric of the society posing a threat to the population’s collective identity. As the country goes through totalitarian dread, human insecurity and hardship, it is hardly surprising to see some Eritreans in diaspora getting caught in a peculiar triangulation and dissonance between the desire to dissociate from turbulent Eritrea and the attempt to identify themselves with the relatively stable Tigray region. Although they are political outliers, individuals’ evasion, and identity dissociation during dark and traumatic situations are not a new phenomenon in Eritrean history. In the 1940-50s, there were few Eritrean Christian highlanders who advocated for the incorporation of highland Eritrea into Tigray. Fresh out of European colonial servitude and manipulated into an unreliable new political marriage with Ethiopia, it was highly turbulent times, but formative decades of Eritrean political consciousness and emergence of Eritrean nationalism where citizens were charting the road for the future, navigating through political uncertainty, and the perilous waters of the struggle for independence. Eventually, in defiance of the Ethiopian empire and the pro-Tigray or pro-Ethiopia elements who were thwarting Eritrea’s prospect for self-determination, the Eritrean population had coalesced around common purpose-struggle for an independent Eritrea with multicultural, multifaith, multiethnic and unified national whole. Eritrea has since achieved its independence. All the ethnic groups may have different religious beliefs, cultural values, and customs, but they have one national identity that binds them together- Eritrea and Eritreaness.

Therefore, the Eritrean Tigrigna ethnic group, like the other nationals, belongs to this sovereign national identity. The Tigray-Tigrigni movements have neither political leverage nor legality to impose its agenda on foreign ethnic groups. Under normal circumstances, one would expect an ethnic group from the unrecognized de facto state to plead their case to join their sovereign kin to share the resource and power. No, they are implying that a sovereign ethnic group should join their de facto state-to-be.

One of the toughest challenges of de facto statehood is a diplomatic war for recognition and legitimacy. As difficult as it is to achieve without strategic allies and supporters, these extreme political entities think they can achieve it by delegitimizing a sovereign neighboring country. Winston Churchill once famously remarked, “There is only one thing worse than fighting with allies, and that is fighting without them.” Eritrea could be Tigray’s strategic ally in its endeavor for independence. Because no country in the sub-region understands and respects Tigrayan’s struggle better than Eritrea. Instead of posturing a threat to the integrity and stability of Eritrea, forming strategic alliance and cooperative partnerships would be an expedient way to build and enhance the socio-political, economic, and security apparatus of both parties withstanding common regional threats. Unfortunately, as opposed to capitalizing on Eritreans’ goodwill, the extremists have dominated the political discourse of delegitimizing Eritrea as a country. It is a no-brainer to figure out that this would be a critical stage where Tigrayan leaders should make a concerted effort to initiate genuine dialogue, resolve outstanding disputes, reconcile political differences, tame extremists and heal old wounds to garner support, mutual understanding, and cooperation for a better tomorrow.

Reference notes

[1]Eritrea Hub (14 April 2020). The Truth Behind the Hitsats Camp Crisis. Available at>https://eritreahub.org/the-truth-behind-the-hitsats-camp-crisis

[2]Organization of African Unity (1964), Resolutions adopted by the first ordinary session of the assembly of heads of state and government, held in Cairo.

[3]TPLF manifesto known as the “Republic of Greater Tigray” was drafted in 1976 by TPLF leaders with an elaborate plan and purpose of creating an independent Tigray that owns a sea. In an effort to realize this ambitious mirage, TPLF had a vision of expanding Tigray’s borders within Ethiopia, claiming territorial possession of coastal lands within Eritrea and redefining Tigrayan to include Eritrean and some Ethiopian ethnic groups outside Tigrayan borders: a) A Tigrian is defined as anybody that speaks the language of Tigigna including those who live outside Tigrai, the Kunamas, the Sahos, the Afar and the Taltal, the Agew, and the Welkait; b) The geographic boundaries of Tigrai extend to the borders of the Sudan including the lands of Humera and Welkait from the region of Begemidir in Ethiopia, the land defined by Alewuha which extends down to the regions of Wollo and including Alamata, Ashengie, and Kobo, and finally the lands of Eritrean Kunama which includes Badme, the Saho (close to the conflicting area of Zalambessa), and Afar lands including Assab; C) The final goal of the TPLF is to secede from Ethiopia as an independent “Republic of Greater Tigrai” by liberating the lands and peoples of Tigrai. Please see Anonymous (August 3,1998).The Manifesto of the TPLF on ‘Republic of Greater Tigrai’ and The Current Border Conflict Between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Available at http://denden.com/Conflict/tplf-manifesto-98.htm

[4]Stephene Ancel (2015). A Muslim Prophecy Justifying the Conversion of Ethiopian Muslims to Christianity during Yoḥannəs IV’s Reign. A Text Found in a Manuscript in Eastern Tigray. PP. 315-333. Available at https://www.persee.fr/doc/ethio_0066-2127_2015_num_30_1_1592

*Image of Tigrayan women’s demonstration during the struggle era, Shiraro, Tigray, Ethiopia, sourced from tweeter.

Awate Forum