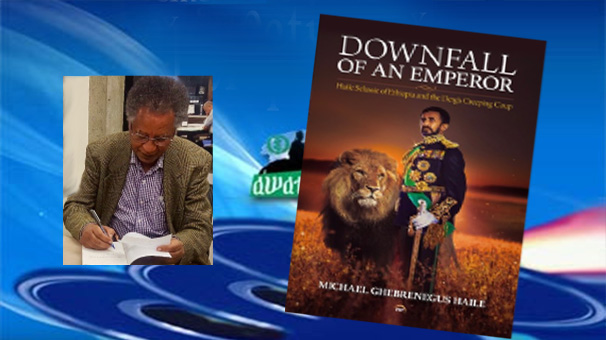

Downfall of an Emperor: Haile Selassie of Ethiopia

Book Review By Semere T Habtemariam

Downfall of an Emperor: Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and the Derg’s Creeping Coup

By Michael Ghebrenegus Haile (Shambel)

Published by AWP | 2024 | 353 pages | Paperback | ISBN: 978-1569024966

First Impressions

On a quiet Friday night, I reached for a book that had been waiting on my shelf for more than two weeks. I hadn’t planned to start it—life is busy, and time, as I’ve come to understand, is not interchangeable. These days I’m far more selective with what I read, careful about where I invest my attention. Some books disappoint. This one rewarded every page.

Until now, I had only heard of Shambel Michael Ghebrenegus in passing—mainly for his role in post-independence Eritrean policing and training. I knew little of his involvement in Ethiopia’s revolutionary transition. But from the first page, I was drawn in. By Saturday evening I was fully immersed, and by 3 a.m. Sunday I had finished all 353 pages. It was time well spent.

A Memoir That Is Also a Primary Source

This book is more than a memoir—it is a primary source. It opens a rare window into the inner workings of the Derg during its formative seven months. Shambel Michael, both lawyer and officer, served on the Planning Committee and the Political, Legal, and Foreign Affairs Committee of the Derg. His account is not secondhand—it is lived, lucid, and unflinchingly credible.

He shows how the Derg began as a loosely organized junta, united only by disdain for the monarchy. Students, workers, and intellectuals had long resisted imperial rule, but only the military could topple it. Its cohesion was tactical, not ideological. Its brutality was not incidental—it was systemic.

The Derg’s View of Eritrea

One of the book’s greatest contributions is its perspective on how the Derg viewed Eritrea—not just militarily, but politically. Shambel Michael details strategic debates and early signs of repression that foreshadowed the regime’s approach to the Eritrean question.

He chronicles the emperor’s faltering response to famine, dissent, and military unrest. The monarchy’s inertia created a vacuum the Derg filled—clumsily but decisively. In foreign affairs, their posture was cautious, pragmatic, and opportunistic. Outreach to leaders like Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere reflected their effort to navigate between Eastern and Western blocs.

Wekiduba and the Shattering of a Covenant

Some of the most sobering insights concern the Derg’s moral contradictions and sectarian imbalances. The massacre of civilians in Wekiduba—my birthplace—on February 2, 1975, remains the defining moment of my life. On that day—later etched into memory as Black Saturday—Ethiopian soldiers slaughtered dozens of villagers, including those who had sought refuge in the church of Qusqam.

In Eritrean tradition, churches and mosques are sanctuaries; Qusqam in particular recalls the Holy Family’s flight and refuge. That day, the Derg shattered a sacred covenant woven into Eritrean tradition.

Even more chilling is the duplicity exposed in the words of Major Mengistu Hailemariam, who once claimed the Derg delayed military action to avoid harming “our Christian brothers in the Eritrean provinces of Akele-Guzay, Hamassien, and Seraye” (p. 297). The massacre at Qusqam proved otherwise—Wekiduba is the heart of Hamassien.

Religion, Solidarity, and Manipulation

The book also exposes the religious imbalance within the Derg—108 members, only one Muslim. This explains why Muslim communities in Ethiopia, led by figures such as Salih Kebire, raised their grievances during the revolutionary period. In Eritrea, Muslims demanded restoration of the Mufti office and recognition of Islamic holidays.

Yet the largest Muslim demonstration in Ethiopia was joined by Christians—proof that when leadership is principled and context ripe, solidarity across faith divides is possible. Identity, rightly understood, need not preclude unity.

The Derg, however, sought to manipulate these concessions—guaranteeing Muslims equal rights “to appease Muslim countries that supported Eritrea”—as a strategic tool to undermine the independence struggle.

The International Response

The international response revealed a markedly different moral calculus. King Faisal of Saudi Arabia openly rebuked Ethiopia’s delegation, asking why Eritrea had been denied independence when every other African colony had been granted its due. Kuwait’s Prime Minister went further, declaring that any military aggression against Eritrea would be regarded as an attack on Kuwait itself.

North Yemen, South Yemen, and Libya joined the chorus, calling for a peaceful resolution. In truth, it was the Arab nations—Iraq, Libya, Kuwait, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Sudan, and Somalia—who stood with us in our darkest hour. We must never forget that. Whatever shortcomings our Arab brothers and sisters may have, they did not abandon us. They stood for justice when others turned away.

Although many of our African brothers and sisters accepted the corrosive narrative that Eritrea was an Arab-aspiring outlier—a sellout to foreign identity—there were a few principled exceptions who spoke with moral clarity. Guinea’s President Sékou Touré affirmed that “Eritrea should be granted independence,” while Uganda’s Idi Amin insisted that “the Eritrean question should find a democratic solution.”

These varied statements, united in principle, signaled a growing international consensus: Eritrea’s right to self-determination could not be denied indefinitely.

Be that as it may, the enduring lesson for us is to shape our regional and international posture in the spirit of prophetic wisdom. As Prophet Mohammed (peace be upon him) taught: “Nor can goodness and evil be equal. Repel evil with what is better: then the one between whom and you was enmity will become as though he were a devoted friend.”

Courage and Integrity Among Eritreans

Another profound lesson is how Eritreans, whether under the monarchy or the Derg, never ceased to protect their people. Their courage is a source of pride—and today, in “independent” Eritrea, a source of sorrow as that culture erodes.

Consider the mass resignation of Eritrean parliamentarians in protest of the Um Hajer massacre. Or the 38-member Elders Peace Committee who refused to speak Amharic when meeting Lij Michael and his delegation in Asmara. Their principled stand—the refusal to compromise on what is right—remains a legacy that future generations must not only cherish, but emulate.

At that meeting, one elder—a former Unionist—delivered an unforgettable line: “We used to say, Ethiopia or death. We got Ethiopia, and now death.” The elders insisted that if the Derg was serious about resolving the Eritrean issue, it must engage in dialogue with those fighting for liberation.

They understood that such dialogue would confer much-needed legitimacy on the Eritrean fronts. But more importantly, they believed it was the most effective and peaceful path toward an amicable resolution to a conflict the previous regime had cast as intractable—a zero-sum struggle with no room for compromise.

Acts of Defiance and Humanity

Even General Aman Andom, deeply Ethiopian, refused to authorize the bombardment of Eritreans in Weki Zagr when requested by the Second Division. Governor Amanuel Andemichael, an Eritrean, informed him, prompting the general to fly to Asmara to avert bloodshed. That decisive, humane act exemplifies the moral clarity at the heart of Eritrean civic culture.

Many Eritreans—among them the author and Ambassador Solomon of Adi Mongonti, Seraye—spoke with courage and clarity. Their integrity is inspiring. I am reminded of another son of Adi Mongonti, Beteweded Abraha. Perhaps the apple did not fall far from the tree.

Yet the question lingers: what has become of Adi Mongonti, and of villages across Eritrea—Kebessa, Weyni Dega, Bahri, and Qola—that once raised men and women of unblemished integrity? Communities where moral clarity was expected, silence shameful, and truth-telling a civic duty. That ethos now feels frayed.

Exile and the Global Echo

Even abroad, Eritreans remained steadfast. Students in France, far from the frontlines yet tethered to their homeland, sent a telegram urging the Derg to pursue a democratic resolution. They condemned atrocities with clarity and conviction.

Their act was not symbolic—it was a continuation of the principled resistance embodied by elders in Asmara, parliamentarians who resigned, and generals who refused to shed innocent blood. These scattered yet resolute voices form a mosaic of integrity—a constellation of memory and resistance. To recall them is to remember what we must restore.

Hidden Historical Revelations

The book also discloses striking revelations. In 1972, Emperor Haile Selassie authorized his UN ambassador to propose restoring Eritrea’s federal status, leading to a meeting with Osman Saleh Sabe. The Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) was never informed.

Later, the Derg nominated Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie as Prime Minister—a potentially transformative moment. But the nomination was blocked by Sissay, a hardline Amhara nationalist, who argued that appointing an Eritrean would incite an Amhara uprising. This episode underscores the ethnic chauvinism that distorted the Derg’s politics.

Personal Witness and the Burden of Memory

For me, this history is not abstract. The Derg’s rise is etched into my life. I was barely five years old when the massacre in my village seared itself into my memory. It is the reason I write—to wrest meaning from suffering, and to redeem memory through witness. That meaning can only be fulfilled through the long-awaited dream of a free, democratic Eritrea—for which so many gave their lives.

The massacre at Wekiduba was not merely a tragedy—it was a rupture. Shambel Michael’s book fills painful gaps in my understanding of that era. It affirms what many sensed but could not articulate: the Derg was not born of vision, but of vengeance.

Tragically, Eritrea has now endured 34 years under a regime similarly devoid of vision or strategy. Its only guiding principle is the ruthless imperative to remain in power—regardless of the cost, regardless of the damage to justice, dignity, or national cohesion. As Sun Tzu warned, “An evil man will burn his own nation to the ground to rule over the ashes.” Isaias appears hell-bent on proving him right.

Final Assessment

This book is not only about Ethiopia. It is about the moral cost of revolution without reconciliation, Eritrea’s place in a shifting empire, and the burden of memory—how we carry it, how we write it, and how we redeem it.

Shambel Michael writes with clarity, restraint, and courage. His account is reflective, not polemical. For those of us who lived through the Derg’s ascent, it is indispensable.

Closing Reflection: On the Meaning of Historical Witness

To remember Wekiduba, Um Hajer, Ona, Besikdira, Sheib, and so many other massacres is not simply to mourn—it is to resist erasure. These were not isolated tragedies but systematic violations of a people’s dignity, carried out in the name of empire and repression. And yet, Eritreans—whether civilians, parliamentarians, elders, or soldiers—responded with unmatched courage.

Historical witness demands more than recollection. It requires moral reckoning. It asks us to honor those who spoke truth to power, who refused compromise, who stood for their people at great cost. The elders who confronted the Derg delegation, the parliamentarians who resigned, the officers who averted bloodshed—these are not just historical figures. They are moral beacons.

Reading Downfall of an Emperor reminded me that Eritrea’s greatness has never resided in its institutions, but in its people—their integrity, defiance, and responsibility to one another. Even under regimes that denied their nationhood, they preserved the soul of their country. That ethos of principled defiance and communal duty must be recovered.

Because historical witness is not passive. It is active. It is generational. It is the vow we make to those before us: their suffering will not be forgotten, their courage will not be wasted, and their memory will guide the justice we pursue.

A Crossroads That Demands Moral Clarity

It is often said that history repeats itself when its lessons go unheeded. Eritrea now stands at a precarious crossroads, burdened by an aging autocrat whose grip on power grows more brittle by the day. His conduct resembles that of a mediocre high school history teacher—pedantic, evasive, and utterly disconnected from the gravity of national leadership.

His days are numbered. And any sane, responsible Eritrean knows that the country must not descend into the kind of chaotic power struggle that has plagued Ethiopia and other vulnerable nations. The stakes are too high, the wounds too deep, and the memory of past sacrifices too sacred to allow history to repeat itself in tragedy.

Public dialogue is essential to the healing process. But if it is not guided by principled and responsible intellectuals, it risks being derailed—co-opted, confused, or rendered counterproductive. That is why those of us with the intellectual wherewithal and resources must step forward. The moment demands clarity, courage, and moral leadership.

Shambel Michael’s book offers profound insights—precisely the kind of work we ought to be studying if we truly care about the salvation of Eritrea. It challenges us to confront our history with clarity, humility, and purpose. In times like these, such literature is not a luxury—it is a necessity.

To purchase the book, please click here: The Fall of an Emperor

____

The author and reviewer can be reached at: weriz@yahoo.com

Awate Forum