Between Approbation and Anathema Justice Suffers

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past. All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.” Faulkner, W. (1955), “Requiem for a Nun”

This is a reflection on the insightful conversation between Daniel Teklai and Saleh “Gadi” Johar, which garnered significant attention after being presented by Hadish Alem on Setit, April 1st, 2025.

First and foremost, elation is par for the course for anyone who listens to the thought-provoking, mind-expanding, engaging, and enriching dialogue of give and take that took place between the two bona fide – through and through – Eritrean spirit. This was the closest one could come to feeling pride in seeing Eritreans who can work through their differences via dialogue. The most impressive part of it all is this: the conversation was respectful, yet persevering through their respective positions as assertively and inoffensively as possible. Genuine, yet careful, framing each of their ideas and underlining their principled stands. Reconceptualizing pragmatism to confront the cyclically vicious political discourse that Eritrea is endowed with.

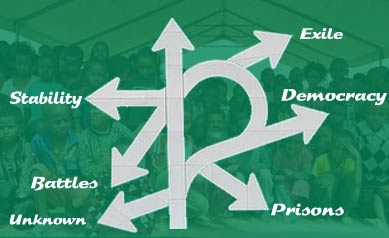

The two distinctly defined approaches both took were on opposite ends of the spectrum. Saleh wanted to arrive at a democratic system via justice (ፍትሒ) while Daniel wished to do the exact opposite. The former’s point is that if a society or a political system starts with justice, it can transition toward a democratic system seamlessly. Daniel, on the other hand, is willing to see it as a matter of prioritization; the institution of justice is one of many other institutions. Therefore, if a government starts with developing infrastructures, educational institutions, healthcare services, water reservoirs for agriculture, and the like, that should be taken into account as the project of nation-building forges forth.

Daniel, by not acknowledging the significant distinctions among various governmental institutions, he risked being misunderstood, and a not-so-careful listener might interpret it as an inability to differentiate between animate and inanimate objects and objectives. In other words, by not making nuanced distinctions, Daniel might be perceived as lacking in ascertaining potential threats and resources; thus attributing actions or intentions to inanimate objects as if they were capable of making choices or having goals, which teeters toward anthropomorphism. Above and beyond all that, taken to its logical conclusion, Daniel might be, again, misperceived as dispensing similar qualities or purposes, potentially blurring the lines between agency, intention, and purpose that each institution possesses and citizens ought to appropriate.

The blurring of institutions that offer fundamental dignity to a society with other institutions on equal footing creates this rift or dissonance in an activist. What one must ultimately consider and end up missing with such blurrings is the dire consequences a society pays when not starting with a just justice system. What one glosses over by not giving a priority to justice as a cause is an impotent, incompetent, and ineffective justice system that fosters mistrust in governmental institutions, invariably promoting social disharmony and lack of cohesion because everyone is not held accountable for their actions and the law is not applied fairly. Additionally, lacking a robust justice system that should act as a check on the power of the government becomes an instrument to abuse and empower individuals who are in a position of authority, thereby depriving individuals of their rights to due process of the law.

What one might surmise from the genuine exchanges above is that Daniel, by default, is willing to delay justice, a laissez-faire attitude toward justice akin to the late MLK, who showed ample patience when he uttered the oft-quoted phrase, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” In other words, justice, freedom, and equality will inevitably come forth, but patience is the virtue, while individuals like Malcolm X’s retort was swift about accepting the idea of justice but emphasized the need for due diligent intervention by justice seekers; Malcolm X did not trust those who were to do right unless they were pushed to do so. In other words, justice could not possibly arrive on its own; activists must keep pushing for the required change.

Considering the above iterations, what a listener may arrive at is that Daniel doesn’t see working toward social justice as an urgent matter. He seems to accept the notion “justice delayed” is not quite “justice denied” yet.

Saleh, on the other hand, feels the need for a sense of urgency in the matter, taking a moral position of the same MLK quoted above, who asserted that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” That “justice delayed is justice denied.” If anybody is unfairly detained, it is one too many, which appears to be Saleh’s position. Justice is the bellwether and the be-all and end-all. Period.

Now, if we were to look at other countries as an example from recent sociopolitical experiences, it will shed light on the fact that “the past is never dead” and “it’s not even past”; that we are helplessly swayed and held hostage by our past for eternity. Let’s then take two educational systems in two different countries: namely, Libya and Iraq.

In Libya’s case, by all accounts, Qaddafi made a great deal of strides in improving the standard of living of every Libyan citizen. The improvement in education under Qaddafi was astronomical. So was the literacy rate of the population. We all have seen the tragic ending his life took abruptly. Any of the indexes made to improve the lot of the population could not save the man because he did not give any civic and political space for the population to latch onto. Saddam Hussein’s sociopolitical and economic trajectory was no different than that of Libya, if not better. Therefore, there is no need for belaboring the issue. His life ended violently as he led his people by the sword, and he died by it. The point is the two countries created a repressive system that inculcated in their nation-building. Particularly, Iraq had no tolerance for any opposition; it had a Revolutionary Court, a State Security Court, and a Special Provisional Court used to violate the rule of law.

Eritreans always are made to feel the sense of duty bound to obey when their country calls for the ultimate sacrifices; they should also equally make demand for the privileges that come with such selfless acts. Another lesson that can be gleaned from this is that Eritrea’s case will be no different than the two countries cited above unless a reform is instituted while the current governing body is at the helm of political power. A follow-up question that I would’ve liked to ask Daniel when he mentioned that there is a justice system in Eritrea. And when he did meet some of the political decision-makers, did it dawn on Daniel to give the same courtesy visit to the justice system? Probably not. Or was that a no-go because it was at the bottom of his totem pole list of priorities?

ERITREA: ኪንየው ፍልልያት ፖለቲካዊ ርእይቶ: (April 1, 2025)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3BNOY_z-RQ&t=55s

Awate Forum