Of True, Half and False Revolutions: Perspectives on the Sudanese Uprising

This piece poses three specific and interrelated points: the character of political revolutions; implications of the 2018-2019 Sudanese popular uprising and; a self-questioning note by its author as someone not directly involved in those events.

The idea of revolution

In its intensity, revolution resembles the forces of nature. Revolution strikes like a quake, storm, tsunami and volcano. Revolution implies fast and furious action, culminating in far-reaching structural transformation. Revolution bulldozes anything, indeed everything that stands in its way. Revolution is about forging a new society and a particularly ethical human being. It is also about shouldering the cost that comes with that prospect.

By definition, the revolutionary moment cannot be delayed. To let up when the revolutionary tide is at its peak and the balance of forces in one’s favour, risks presenting remnants of the old regime the chance to regroup and to mount rearguard action. Having once gained the upper hand and when on the verge of victory, advocates of revolution know they cannot hold back and must push ahead. As men and women committed to (creating) a new dawn, their first duty is to enforce the popular classes’ agenda irrespective of all other considerations. The stakes are high at the same time as the scope for making decision proves to be quite limited. And that is because the exact hour of revolution confronts the sides as black and white, making it impossible for anyone to sit on the fence. So, for the leaders of a revolution to behave indecisively at this point, is to commit a serious (tactical) error that portends long-term loss and suffering. History duly teaches the living that those who make revolution halfway only dig their own graves. Such is the nature of this deadly ‘game’ called revolution where nothing is guaranteed because instead everything hangs in the balance. As the prominent (past and present) revolutionaries of the world would readily aver, most people who pursue true revolution either win or die! Likewise, any effort expended in the name of revolution stands a better chance of being consummated if it is also bolstered by certain fundamentals. In the end, victory anticipates a mix of greater organisational potential, clarity of vision and men and women of the hour. Absolute discipline, mass mobilisation and an ingenious (economic and political) program along with accomplished leadership are the ABCs of the deal. That, in general, is what the political sociology literature imparts about revolution as concept and praxis.

A country’s desire for real change yet to be delivered

Considered against the above criteria, how can the latest unrest in Sudan be understood and explained? Or, where may Sudan’s insurrection possibly fit within the spectrum of true, half and false revolutions? Based on events on the ground, the Sudanese uprising indeed comes across as a genuine struggle for profound economic, political and social change. It is even thinkable to call the recent political developments in the country a revolution, although some necessary qualifications need to be pointed at the same time.

The most plausible designation however could be this: that it was initially a true revolution but got degraded to a quasi-revolution over the course of time. And yet this is not to take away from the Sudanese popular forces’ incredible determination and hunger to see lasting change. No doubt, the Sudanese youth in particular have fought so heroically for all out change. This has been confirmed by the way many of them paid the ultimate price. On this particular occasion, the internal and external forces arrayed against them may have proved too much to defeat comprehensively. True to its treacherous character, the Sudanese comprador class (civilian and military) allied itself with its foreign handlers and did all it can to thwart the people’s aspirations. Dare I say it too that the Sudanese technocrats who were tasked to oversee the people’s struggle did lack the thorough revolutionary credentials that such a (historic) conjuncture calls for. They have bargained so much that their actions can perhaps more easily be likened to that of the petty bourgeoisie than a revolutionary force capable of conquering state power. These self-proclaimed spokespersons symbolise an elitist social stratum which is nothing close to a vanguard bottom-up revolutionary organisation.

So, to recap, the civil disobedience that the Sudan saw in 2018-2019 is clearly not a false revolution when judged by how the populace rose up against the inept regime. What lends additional credence to their cause is also the fact that the regime lacked any vision to move the country forward economically and politically. Relying instead on obscurantist policies (religion) to keep itself in power for so long cannot (and never will) address the peoples’ substantive needs. Ultimately, theirs is an unfinished revolution since those same original conditions still plague the country. To transform their nation truly, the Sudanese people may have no other way but to revisit the question of revolution down the track and not before long.

Who says what, when and how?

A revolution is strictly the business of those implicated in its making. Only they have the final word on the changes which will directly affect their lives. In that case, how must anyone not immediately involved in those types of events communicate his or her perceptions? Isn’t it redundant to state the obvious about a (political) contest you are not part of? How do you avoid the charge of theoreticism when discussing others’ actions taken to the best of their ability and knowledge?

Outsider review of events that have historical significance typically comes with potential pitfalls. The problem of reporting from abroad on domestic upheavals, like the recent political developments in Sudan for example, is closely tied to spatial and temporal questions. Here is how I wish to present/ justify my views as an external observer of the recent social strife in Sudan.

As I express those thoughts about the latest Sudanese intifada, I realise simultaneously that I am commenting at a remove from the real-time revolutionary events. Following the lessons of history and sociology, there is the need to therefore frame one’s point somewhat reflexively. Reflexivity describes a vital methodological tool in the social sciences, a field of knowledge in which I have been duly initiated. It implies self-awareness about one’s thoughts and everyday lived experience that is supposed to facilitate social inquiry. If a person is properly trained in reflexive practices, that person tends to be especially mindful of his or her biases and its practical ramifications.

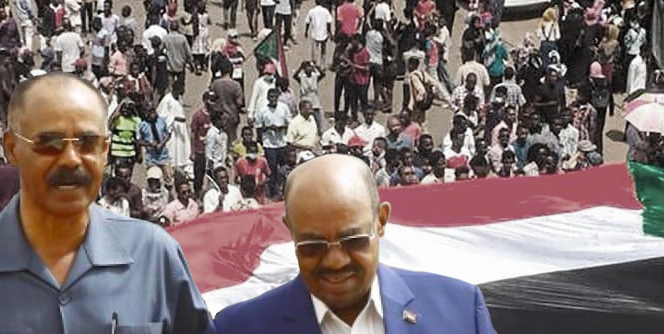

Obviously then I can’t simply be motivated by a desire to criticise for criticism’s sake when deliberating on the political events that have played out lately in Sudan. Still more, nor can my intention in this instance possibly involve vulgar revisionism or cynicism of any sort. Unlike the revisionist and especially the cynic who after the fact knows the price of everything and the value of nothing[1], I truly appreciate the efforts (with all its flaws) of those at the centre of revolutionary upheavals. Frantz Fanon, famed for his straight talk, for example, laid it out that when we revolt it’s not for a particular culture. We revolt simply because, for many reasons, we can no longer breathe.[2] And that exactly is what the experience of the people of Sudan has been under the regime of Omar Al-Bashir when they rose up against it.

So, the key point comprises not in how exactly those events unfolded, or where the political process really ended. Rather, the real issue comes to be specifically that the people lived through an important juncture when many of us could only watch from the margins. This should make it incumbent upon those following the situation from afar to bring good judgment to bear on what they say and how they say it. The clever thing is to be able to tell, amid the prevalence of conflicting perspectives, what matters in reality. A touch of wisdom interspersed with basic logic thus goes a long way to reduce the risks inherent in conversing about the internal affairs of others. In particular, it can only be correct to endorse the will of the people and their sacrifices which delivered some form of outcome. And to be able to acknowledge the (fighting) spirit of the people requires putting an end to all patronising retrospective judgement. Again, if the final political outcome has come to be dissatisfying, the proper thing would be not to dismiss the people as incompetent but to draw lessons in light of what has happened. Indeed, in defence of the people and their (half-finished) struggle, the conscious critic may argue that ‘the only battle lost is the battle not fought’. Ultimately, it is this sort/ level of empathy which could justify the present account even as both time and distance separates its author from the issues being addressed. Similarly, following a self-reflexive analytic policy, the author doesn’t believe the general observer first knows the trajectory of those political events before he or she can provide a realistic assessment. In other words, it is entirely sensible to debate an issue in hind sight although it all depends on how one communicates what one wants to say. And so, whilst seeing real need for serious critique, the author admits that in practice what matters is the Sudanese people’s standpoint.

___________

[1] The expression “a cynic is a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing” comes from a character in one of Oscar Wilde’s comedies.

[2] See: https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/648759-when-we-revolt-it-s-not-for-a-particular-culture-we

Awate Forum