The Death of Mihret Eyob as an Illustration

The Eritrean tragedy is not obscure to anyone who follows current events; there is an international awareness about the thousands of prisoners of conscience in the country. And Eritreans know that the awareness about their plight is a result of a dedicated and resilient struggle by people of goodwill, and Eritrean activists who made sure the victims are not forgotten. Unfortunately, the role of most of the relatives of the prisoners, their friends and close associates, in fighting for the freedom of the victims, has been abysmal. In fact, the silence of some of them borders on complacency.

Regrettably, those who should be on the forefront demanding freedom for their loved ones, those who should spearhead the struggle to end their suffering, are not as visible as they should be. Ideally, exerting pressure on the culprit to free the victims should have been the concern of the timid relatives and friends of the imprisoned, who are selfishly living their lives as if nothing has happened.

Nevertheless, it’s an established fact that the Eritrean regime is vengeful and has a track record of punishing relatives of people who escape the indefinite servitude it imposes on the youth. It humiliates the relatives of its opponents it can’t reach, and sends threatening signals to those who might inflict damage on it if they opened their mouth. It’s also known for its sadistic behavior and its emotional abuse of innocent relatives to inflict maximum pain on its real or perceived enemies. And that is the cause of the deafening silence of some people who feel so much threatened that they prefer to be quite despite the pain.

Understandably, it’s difficult for anyone who is not in their shoes to appreciate their situation—they are anxious and blackmailed individuals who live in agony. However, it is fair to assume that they can do a lot better than complete silence. Here, the main observation is not necessarily concerning the blackmailed individuals per se, but the entire Eritrean society.

Sadly, the Eritrean government’s blackmailing tactics have encouraged a few people to shamelessly peddle their silence as a virtue, and to pledge allegiance to the misleadingly named segment, “Silent Majority”, a brand they hide behind, and portray as an epitome of wisdom. Can an affected person, or anyone else for that matter, be consciously silent about the plight of the prisoners? Importantly, what is the value of an Eritrean life and a citizen’s freedom?

The value of life and freedom

One can confidently say that the rulers of Eritrea have managed to cheapen life, though throughout remembered history, Eritrean lives were squandered for one cause or another, by one despot or another, with only brief intervals of peaceful time. Not unexpectedly, the last epic struggle that Eritreans waged for self-determination was the first they ever fought as a nation and paid a heavy price for it. Unfortunately, the ruling regime conveniently forgot the struggle was in pursuit of freedom and human dignity; it behaves as if it was to replace one tyrant with another. Worse, it took the sacrifice of Eritreans for granted and carelessly uses it to advance its narrow interests. Therefore, it’s not difficult to recognize that the regime loathes the concept of personal and communal freedoms, when it doesn’t value human life. But is that disregard for life and freedom a characteristic trait of the ruling regime, or a social attitude of Eritreans?

Human beings deal with death and afterlife in so many ways. Hindus and Buddhists believe that the body perishes while the Atman (sprit) is reborn repeatedly in other forms of Samsara (reincarnation), based on karma; a righteous existence can release the soul from the cycle of karma to nirvana, an existence of no suffering or desire. Generally, followers of Abrahamic religions believe that the body perishes, but the spirit goes through a divine trial in the afterlife to either live eternally in heaven, with God, or receive varying degrees of punishments in hell. And Atheists believe that the body decomposes and is reduced to its natural elements in a process of recycling, and finally it mixes with earth, water, and air.

In the Middle Eastern cultures, people who die in a political conflict are considered martyrs whose soul go straight to heaven—no questions asked! That is why when a government soldier or a rebel fighter die fighting against each other, both are considered martyrs by their respective parties—even if it is a civil war. That culture, which is supported by divine scripture, is well established in the region, and that is why most people do not die, they are martyred. However, Eritreans face a dilemma when a victimized prisoner and his jailer die: are both considered martyrs?

The Eritrean regime defines death depending on how loyal the dead persons is to the regime— based on the level of loyalty, the deceased is either martyred, or just “pass away”. Without loyalty to the regime, a lifelong service to the nation doesn’t weigh much.

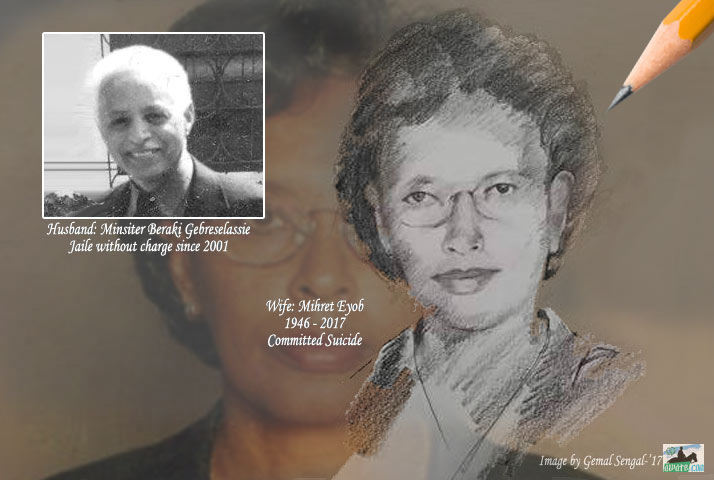

The Isaias regime killed Mihret Eyob

On April 14, 2017, the government-media announced that the “Veteran Fighter Ms. Mihret Eyob has passed away aged 65.” She was not martyred as the rest of her colleagues—unless the PFDJ suddenly embraced its atheist nature and simply abandoned the tradition of martyrdom!

Sadly, not many people mentioned Mihret while she was alive and was separated from her husband by the cruel regime since 2001. Now that she is dead, there is a flood of articles, poems and obituaries eulogizing her. Why were all silent? Is a dead Eritrean worth more than alive? What is the value of freedom? Where are the relatives who should be screaming before the victims die?

The answer is fear, real or perceived.

In PFDJ’s Eritrea, talking about a family member makes you selfish and individualistic, talking about the suffering of your village people, makes you clannish, talking about your province, makes you a regional, talking about religious rights, makes you a sectarian—the only kosher topic the regime tolerates is empty sloganeering. And so many, including the hyphenated affiliates of the rulers of Eritrea, repeat its propaganda and help erode natural values and freedoms, and maybe inadvertently help break up the family unit. Undeniably, some elements (and vested interest groups) abuse the natural affiliation of people and their natural identities, to wreak havoc among the people. But that cannot be prevented when Eritreans are atomized and they live suspecting and fearful of each other. Unfortunately, some people are so intimidated they have internalized the ruling party’s justifications or are so selfish they do not feel obliged to fight for the rights of their relatives let alone their compatriots. The life and death of Mihret illustrate that Eritrean tragedy.

On April 14, 2017, the ruling party’s website announced that Mihret “passed away.” However, the last sentence in the announcement, though it sounded more like an afterthought than a natural continuation of the announcement, was obviously a face saving attempt: “The funeral service of the late veteran fighter Mihret would be conducted today, 15 April, at 4 o’clock at the Asmara Martyrs Cemetery.”

At least her body was allocated a burial space with other martyrs.

Mihret Eyob joined the Eritrean armed struggle in 1978 and became a teacher at the revolutionary school. After independence, she served in many capacities and was a member of the constitution commission. She had a master’s degree from the Birmingham University and was the wife of Beraki Gebreselasse who has been in prison without charge since 2001.

Beraki Gebreselassie, abandoned his teaching job in 1971 and joined the Eritrean armed struggle. He was the head of the educational department of the EPLF. After the independence of Eritrea, he first served as minister of education and then as minister of information. Habtom Yohannes, an Eritrean-Dutch citizen who worked on some project with him wrote, Beraki refused to shut the nascent media stating, “I don’t want to be remembered as the minister who closed media and who jailed journalists.” Apparently, that’s when Isaias Afwerki pushed him out of the country as an ambassador to Germany. In 2001, he was arrested together with his colleagues who came to be known as the G15, the imprisoned senior government officials whose whereabouts are still unknown.

Mihret took care of her family alone, and saw the children she raised grow up only to be conscripted into the indefinite servitude by the regime that jailed her husband. Being an employee of a regime that makes your husband disappear, and takes away the children you raised alone, and living under its mercy, must have been too painful to endure.

Though the Eritrean government indicated that Mihret died of natural causes, there are rumors that suggest that on the morning of April 13, Mihret jumped off the ministry of education office building where she worked, and committed suicide. According to some reports, the draft announcement initially read that her death was an “accidental death”, and that it was later changed by the president’s office to read, “she died after she was being treated for a sickness inside Eritrea and abroad.”

No one contests the fact that she died in the morning hours of the 13th. And if she jumped off the building in broad daylight, in a major street in Asmara, in a building that borders a busy promenading sidewalk, in a ministry office where there are dozens of employees, facts cannot be that obscured.

Many who agonized like Mihret for too long have either lost their minds, or died a slow death. She was not different, but a visible and known victim. The PFDJ government was killing her slowly since it jailed her husband. And there are thousands of children, spouses, and parents who are suffering silently like she did. They are being killed slowly by the monstrous Eritrean regime. Mihret was killed by the regime. May she rest in peace.

NB: Drawing by Gemal Sengal

Awate Forum