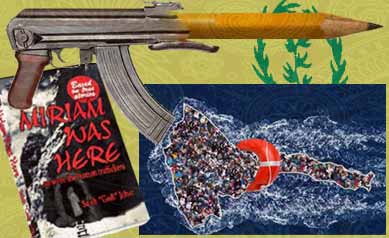

Zerom The Liberator

Now that the endless “silver jubilee celebrations in Eritrea are over, and the epic trip of the torch that remained the only featured star on PFDJ’s media for about five months is over, I felt of sharing the following chapter, “The Liberator”, from my latest book “Miriam Was Here”. Consider it my way of expressing the human and heroic dimensions of the Eritrean liberation struggle, as opposed to the partisan peddling of “Liberation” as a propaganda vehicle by the totalitarian regime, not as a combined Eritrean national feat. I invite you to retroactively follow Zerom when he entered Asmara on May 24, 1991, the date after which the brave combatant was betrayed by the PFDJ clique.

In the early hours of the fourth day of the battles, Asmara fell to the rebels, but Zerom had no immediate family members in the capital city he helped liberate. His three brothers and his sister, fellow rebels, were not there to receive him; now he only had the combatants of his battalion for a family.

The rebels had advanced so close they could see the buildings of Asmara from the surrounding hills. Zerom felt it was an unusually cold day for May as he looked through the mist and observed his old city, focusing on Forto Baldissera and wondering how the people coped with life in his absence. Since the port city of Massawa had fallen to the rebels a year earlier, the supply flow to the capital had been choked. Civilians survived on meager food smuggled from the countryside, while the army depended on Antonov military planes that brought them rations over an air bridge that connected Asmara with Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital.

The tense situation in Eritrea, and in their country, had made the few Russian military advisers who remained, fatalistic. They were shaken by the fast advance of the Eritrean rebel forces. The news coming from the Soviet Union didn’t help either, they were not sure if anything would be left of it when they returned home.

Although the city didn’t go through war, the looks of the dilapidated buildings made it seem uglier. Under the overcast clouds, everything appeared grayer than it really was. The white traditional gabi cloth that the locals wrapped around themselves looked soiled and acquired a ting of brown shade. The mixture of fading khaki and green uniforms of the soldiers, and their vehicles, suppressed most other colors. It blended into the gray shade that overwhelmed the city. Only the color of the bright navy-blue attire of the ruling party officials and operatives remained prominent.

The Ethiopian military had banned pedestrians from using the walkways where they installed barricades made of rocks, sand-filled sacks, barrels, and used tires. Behind it lurked soldiers with fingers on the trigger; they panicked if anyone got closer and bellowed to keep them away. People avoided the walkways and paced in the middle of the street, along with the military vehicles and pack animals.

Battles had been raging around Dekemhare, a town forty-five kilometers south of Asmara, but no one had dared hope the last three days of intense fighting would mark the end of the long journey of struggle that lasted three decades.

Having taken Dekemhare, the rebels had planned for the final showdown with the Ethiopian forces and began to build defenses on the road at the village of Adi Hawsha, close to Asmara. But since they didn’t find any significant resistance, they marched towards the capital city chasing the enemy. Zerom, a popular machine-gunner was with the vanguard of the rebel forces. For a month before it liberated Dekemhare, his battalion had suffered great losses; after that, it had been mowing the retreating enemy forces and continuously gaining territories.

Corpses of soldiers remained strewn on the sides of the road, the ravines, and the foothills. No one could tell if the bodies belonged to the rebels or the enemy. In the past, the fighters found it easy to identify the dead by their clothing. Ethiopian soldiers had boots, uniforms and field jackets, while the rebels were mostly in tattered rags and plastic sandals. Now they couldn’t tell from the clothing: it must have been a long time since the Ethiopians received new pairs of uniforms: their clothes looked as bad as that of the rebels.

But since the Ethiopians were in a retreat, while the Eritrean rebels advanced, it became easier to distinguish the bodies of friends from foes. They buried some of the dead but left many others in the open; they were too many and the forces had to advance fast to control the few kilometers left to capture Asmara.

Carrying a machine gun, and wrapped in bullet-belt, Zerom found himself in the southern edges of the city looking at the streets of his childhood. He felt like crying, overjoyed to have witnessed the end of the war. At the same time, he felt sad for he couldn’t rush to see his parents. His mother had died in his absence, and his father had moved to the outskirts to live in his village when he couldn’t tolerate the tense life of Asmara.

Zerom was still in a pensive mood when his battalion started to move; they had an order to occupy the main fortress that served as a camp for the Second Revolutionary Army of Ethiopia. This time the rebels didn’t walk the distance, they had captured enough Ethiopian army trucks to transport them there. Zerom mounted a truck that passed through the city center amid euphoric public singing and dancing. He remembered the streets, and could tell nothing had changed, but he couldn’t recognize anyone among the celebrating crowd as he unconsciously waved his hand at them.

The truck passed by a corner close to the sidewalk where he had a fruit stand before he joined the rebellion. It used to be busy with people who carelessly glanced at his stall as they walked by. Some stopped to cuddle an orange, or a mango, like a shepherd cuddles a breast of a goat before milking it. They toyed with the fruits and then they simply dropped them back and left without asking for the price. Now the place looked empty, deserted, unlike how Zerom remembered it; he felt relieved no one had occupied it in his absence.

More crowds filled the streets and the truck moved slowly between them, and made a final turn to a street that led to the fortress.

Two guard shelters that resembled upright coffins occupied the sides of the gate. Ethiopian military police used to squeeze themselves in them and chastise soldiers returning late from the city after a drinking binge. Now there were no guards. The fort was filled with wreckage and abandoned vehicles and equipment; Ethiopian troops had left everything behind as they escaped on foot to the west, towards Sudan.

While his colleagues were exploring their new home, Zerom found a mattress leaning on the side of a building. A soldier had probably thought of aerating it under the sun before he fled leaving it behind; he probably didn’t know he would never sleep in it again when he took it out.

Zerom moved the mattress to a shaded area, flung himself on it, and stretched his legs. His eyes felt heavy, he hadn’t slept much for the last two-weeks, only relaxing for a few minutes every time the raging battles slowed down. Now he began to think about the fruit stand and decided to reclaim it soon, maybe expand by renting the store behind it. He had seen enough; his long journey ends here. He went to sleep.

Late that evening someone woke him up for dinner, but he didn’t feel hungry or thirsty. He ate a small bread, washed it down with tea, and went back to the mattress to relax some more. This time he didn’t sleep, the incidents he went through for the last seven years came to his head and he drifted into a pensive mood.

Zerom vaguely remembers the Ethiopian emperor, he had heard horrible stories about him since his childhood. The reign of the king seemed too far, he felt removed from it, and it seemed to him like fairy tales made alive by his father’s repeated stories. Only hazy memories remain in his mind of the time when the king met his demise by the derg, the Ethiopian military junta under whose rule he grew up.

Zerom got lost whenever his father talked about Italian and British rule, two eras that he imagined were set in the Stone Age, long before he was born, long before anyone was born. It could have been when Adam and Eve roamed the world. He had heard the British pushed out the Italians, and many people blamed them for the crisis that followed, and for the ills of the country. They blamed them for being the cause of the decades of war that Eritreans had to wage to regain their country’s independence that the British thwarted.

Zerom couldn’t tell whom he hated most, the Italians or the British. His father never had a conclusive opinion on the two, but judged them based on reasoning that he altered to support his argument at any given time. Zerom never understood his father’s ambivalent views. Sometimes he seemed to admire the Italians, “Oh, the way they construct roads and buildings! They are the best.” In a minute he despised them, “They enslaved the people. Racists!” After a while, he idolized and demonized the British in a single sentence, “They were good, they introduced freedoms; but they are wicked, they destroyed what the Italians built.”

“But father, who was better: the British or the Italians?”

“You donkey! I am not talking about politics.”

“Now you are father.”

“No, I don’t like talking about politics, I am talking about occupations.”

“Well, the Ethiopian occupation is just that. It is politics.”

“No. I don’t talk about politics, but Ethiopian occupation is different.”

Zerom’s mother had nothing to say in such discussions, she just fumbled her rosary beads and moved her lips in a silent prayer.

His father sipped his coffee, “Cursed be the British; they gave Eritrea to the king as if it was a bag of fruits.” His parables and examples were all about fruits and vegetables.

“Speaking about fruits, father, I don’t have any to sell today.”

“Sell beles fruits.”

“You want me to sell beles like the Agame people!”

The wild cactus plant grows abundantly around the city, but even the poor urbanites of Asmara considered harvesting and selling it beneath them. According to them, that was a job fit only for Ethiopians from south of the border, the Agame.

That angered his father and he scolded him, “Foolish. The Agame earn clean money selling beles. Now go and do some work… didn’t you refuse to go to school?”

His mother interjected, “Son, pray to God. May St. Mary protect you, go and find your bread. God bless you, my son.”

No trucks or buses arrived in the city and Zerom depended on smugglers who brought him fruits on pack animals from Keren or Ghindae, two towns located northwest and northeast, an hour away from Asmara. But in a few hours, the fruits rotted and he trashed them and returned home with a loss. Finally, the smugglers disappeared altogether after the Derg soldiers killed three of them near the entrance to the city. Those who survived were frightened and stopped venturing to Asmara altogether; Zerom couldn’t find alternative suppliers.

There was no means left for earning bread when everyday news about battles that raged in the outskirts flooded Asmara. People gossiped about a blown up bridge somewhere, and a blocked road somewhere else. Every time a landmine laid by the rebels exploded on a road, the Ethiopians closed the highways for weeks.

“This country is cursed,” Zerom had told his father.

“You are cursed, not the country.”

“Father, first came the Turks, then Egyptians, the Italians, and the Ethiopian emperor, followed by the Derg. It is cursed.”

“What do you know about all of that except the anti St. Mary Derg, huh? Keep quiet; don’t talk about things you don’t know.”

“I know this country has been always fighting, always miserable. What else happened but war, always on behalf of others? Fighting for the Italians, fighting for the Ethiopians…”

“You are foolish, what will you do if the government forced you to bear arms and fight? Do you think people liked wars? They wanted to survive. Sometimes it happened to be the only job available; other times they forced it on the people. Wars, wars, wars. It is bad… but no choice.”

“But father, this is the first time Eritreans are fighting for themselves to kick out occupiers and end all wars.”

“Little child! Worry about your safety and about earning your bread. Stop this nonsense. If you over stretch your tongue and get in trouble, no one will save you. I am warning you.”

“I don’t have to stretch my tongue; the Ethiopian soldiers kill people for no reason!”

“I said it’s none of your business, behave!”

Zerom had no doubt the Eritrean rebellion was a just fight against the Ethiopian occupation, and he had a reason to hate the occupation troops. They stopped the people for body search and beat them up for trivial reason; sometimes he had to go through five body searches going from home to his fruit stand. Some of his friends had already joined the rebellion and he decided to take action, maybe join the rebellion before he lost his mind.

A few weeks earlier, he intervened to save a girl he knew when a drunken Ethiopian soldier harassed her. Since that day, a few soldiers laid their eyes on him, and he stayed in his house for fear of being killed or jailed.

Whenever the troops disappeared from the city, he felt relieved. They often went to wage battles against the rebels or to support a besieged force somewhere far. But once they returned to the city, his troubles resumed and he had to hide.

Maybe it was time for him to join the rebellion, something he wanted to do since he was a child. Zerom hadn’t worked for months; he had nothing to do in the city anymore and he wanted to leave. Only worries about leaving his parents alone had prevented him from doing so.

They have already lost three brothers and a daughter to the rebellion. Two of his brothers had already fallen in combat and he never heard of his sister; but the family received news about his remaining brother only a few weeks earlier. At least he was alive thus far. But if Zerom stayed in the city any longer, he risked unceremonious death at the hands of a drunken or spiteful soldier, which would be more painful to his parents.

Zerom woke up early morning and joined his parents in the kitchen as they were having their morning coffee sweetened with candies. His mother was complaining about the scarcity of sugar when he came into the sitting room. He sat there but wouldn’t take his eyes off the floor. She glanced at him, and repeatedly checked him from head to toe. He suspected the instinct of a mother might have helped her know of his intentions. Maybe he unknowingly gave her a hint. Nervousness overtook him when she asked, “Are you all right son?”

“I am fine. I am fine, mother.”

“I think you stayed up all night, you look tired. Are you all right?”

“No, I slept…but I was up. I feel tired. I mean rested.” He looked to the ceiling for a while and then asked his parents, “Have I ever wronged you?”

His father knotted his eyebrows, “Yes. You are talking about things you shouldn’t and getting in trouble. That is how you wronged us.”

His mother was anxious, “Son, why are you talking like a dying man? My dear son, how could you have wronged us?”

Zerom looked at his father, “I haven’t been earning enough lately and it will be worse. I feel helpless, I can’t do anything.”

His mother felt his pain, “Don’t worry dear. It is God that giveth.”

Every hour was laden with more risks and Zerom looked restless, he didn’t have much time left. For the first time in his life he had been involved in distributing rebel leaflets in the city, and the friend he collaborated with was arrested. A stranger had tipped him, “Your arrested friend has started to talk and you risk being arrested.” Zerom would’ve liked to spend more time with his parents, but he had to leave quickly, he doesn’t want to be killed leaving to the outskirts when the guards are fully awake. They usually sleep until late morning after spending tense, sleepless nights.

He looked at his parents from the corner of his eyes as they stared at him in bewilderment, “Bless me.”

His mother was quick, “May St. Mary protect you, may you step on solid ground, may you live long. Where’re you going?”

Zerom acted strange and his father noticed that, but before he could ask any questions, he jumped off his seat, kissed his mother’s forehead and his father’s knees and said, “I have to leave now.” They tried to persuade him to talk to them, but he was out of the door and to the street before that. They avoided following him there fearing a cacophony might invite the attention of the Ethiopian spies. They froze there wondering; they never saw him in such a strange and gloomy mood before.

Hardly a day passed in his life in which Zerom didn’t see his parents, he knew he would miss them. They had always been sad about their dead children though they hid their emotions. He remembered all the years his father waited in line at the government stores, the Kebele, each time for hours, to get rations of sugar, oil, and coffee—something that grew in abundance in Ethiopia yet it was always in acute shortage.

The same with his mother, she spent her days standing in line behind a blue plastic barrel waiting for the water supply tanker. Zerom couldn’t do anything about that as well, he had to attend to his fruit stand; yet he couldn’t earn enough to help them. It has been a very difficult year and it was hopeless and that is why he wished to see an end to the miserable life, which he had no doubt would end once Eritrea is liberated. He believed the hardships would be over.

In fast paces, he walked to the eastern edges of Asmara avoiding the roadblocks and sneaked to the countryside where he met a reconnaissance team and joined the rebellion. He was eighteen.

The next day, he set out with other recruits on an epic journey that lasted three weeks, sleeping by day and walking by night to avoid Ethiopian Mig fighters that flew continuous sorties to bomb the countryside. He saw burned villages whose inhabitants had abandoned them to live in wilderness. When he passed through rebel camps, he found people he knew in the city now armed and proudly smiling for being free from Ethiopian control. It is there that Zerom saw a machine gun, up close, for the first time. He touched and cuddled it. He fell in love with it and dreamed of a day when he would wrap himself with a bullet-belt and become a machine-gunner.

Throughout the journey, Zerom persevered like an experienced rebel and never complained about thirst, hunger or fatigue. That earned him respect before he even started the military training that lasted for three months.

When he finished training and became a combatant ready for the war, they gave him a Kalashnikov rifle, two hand grenades and ammunition; they immediately sent him to the frontlines. His appeal to get a heavy machine gun didn’t bear fruit. The political commissar explained, “Machine-gunners need experience, courage and valor. You need enough experience before you get one. If you prove yourself, you might even become a squad leader in no time.”

The proposal didn’t appeal to Zerom, “Ufff, I want a machine gun to wipe the soldiers who humiliated me all my life. Squad leader? Leave that for the educated combatants like you.”

It took three more years before Zerom became a machine-gunner. When he entered Asmara triumphantly on the twenty-fourth day of May 1991, he was already an established combatant and a popular machine-gunner. On that same day as he lay on the mattress, he decided to throw the gun away and return to normal civilian life. He believed his job was finished.

To his amusement, a few days after independence, the leaders of the rebel organization elevated themselves to de-facto rulers by issuing a proclamation, and formed a transitional government instead of handing power to the people, the main goal of the struggle, as he understood it.

By the time the government issued another proclamation to demobilize and relieve rebels who joined just before Independence Day, Zerom had become more skeptical though the demobilization didn’t apply to him. In his heart, he felt that free Eritrea would have so many employment and educational opportunities. Full of confidence, he believed there wouldn’t be a need for the people to carry guns anymore. Thus, he didn’t see a reason why he should not be demobilized like the rest.

Zerom had no idea they would ask him to continue serving without pay for an indefinite period until the government stabilized the country and built the economy. He objected, “What do I have to do with the economy?” He defiantly stated, “I am a combatant, and fighting is over, I don’t want to be a soldier anymore. My job is finished.” His commanders turned a deaf ear on him even when he reasoned, “I am a wounded veteran and I should go.”

Though Zerom lived with a shrapnel lodged in his skull, he had downplayed it for fear of being pulled out of the fighting forces. If that happened, he would have been assigned to boring places far from the frontline, and he hated places like the clinic and the supply stores.

When Zerom came to the clinic wounded in the head, the doctors didn’t want to operate on him. They found the shrapnel lodged too close to his brain and they feared an operation might kill him. For a few months he stayed at the clinic until the wound healed. Since that day, he knew the piece of metal was destined to live in his head as the commanders thought of assigning him to the rear areas of the frontline. But in the confusion of the wars, Zerom had sneaked out from the clinic and joined his battalion.

Two years after he entered Asmara triumphantly, Zerom was thankful they didn’t consider him a handicapped veteran. The government had housed the disabled rebels, who couldn’t be absorbed in the workforce, in a village in squalid living conditions. They were so neglected they demonstrated to publicize their plight, but the security forces sprayed them with bullets. Many who survived the fierce battles against the enemy fell by the bullets of the government they brought to power. The behavior of the government he helped bring to power worsened, and prospects of the future looked grim.

Two more years later, the government issued another proclamation and ordered everyone between 18 and 40 to avail themselves for a compulsory training and active military service. It soon began to round up thousands of youth and deploy them across the country to work in construction projects for indefinite periods, without pay. In no time, the entire country turned into a huge military camp and the nation became militarized.

You can order the book at : <www.miriamwashere.com>

Awate Forum