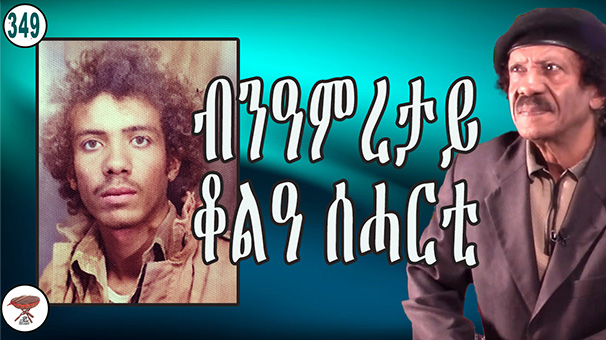

The Beni Amretay Boy in Saharti

A struggle-era picture has resurfaced with confusion for some years, and I promised to clarify a few points in an episode. Today I am fulfilling that promise and will continue to do so in subsequent installments. The series will be rich with information and anecdotes: my meeting with the late Petros Solomon and Ali Sayed Abdella in Karneshim and how they broke my heart regarding the ELF-PLF unity meeting in Khartoum; the Ethiopian army convoy that was on its way to break the siege of Afabet garrison; the battle that was on the Asmara‑Keren road between Shmanegus and Afdeyu; my encounter with the late Dr. Eyob Genreleul; the wounding of the late commander Mohammed Said Baarih in that battle; my brief stay at the Zaghir clinic; and the selfless nun who insisted I take her cane… maybe more.

To me, the picture was taken in eventful circumstances, and it evokes a chain of memories, and it continues to attract interest. It was first posted some years ago and has been reposted many times—with much incorrect information. And the confusion is far from over, and it’s too long a story to be told in one instance. So, I’ll narrate it in a series, hoping to cover as much as possible.

The Intriguing Picture

Last month the image was reshared by Yared Tesfay and several others. Yared added to it a background of the “Kagnew Station”—a worthy addition, albeit missing some details that would have provided proper context.

Tesfai Haile said, “No! These were USSR (Russian) military experts assisting Meles Zenawi before the demise of Nadew Eze.”

Wrong, the demolition of Nadew Ezz happened in March 1988; Melez was not the ruler of Ethiopia at that time, the Derg was; and the picture is from 1975.

Tsehaye Durub commented, “In true Eritrean military style, these prisoners were looked after and released without any repercussion.”

True, they were interviewed several times, and they have confirmed so.

Yared Tesfay wrote, “Saleh Gadi Johar, thanks for sharing your perspective. It’s fascinating that you haven’t yet shared your experiences from these moments. Connecting them to the roles of the GIs, the journalists, and the individuals in the photograph would help us tell a richer story. Why did the Eritrean Liberation Front choose Adi Tekaly? If you were guiding the journalists, share their expressions and how you transported them—on foot, in cars, or by camel. What was it like? How many times did the ELF attack the American base, Kagnew? Did they capture more than those in this instance?… Many of them are still alive; interviewing them would be invaluable. You also mentioned Zaghir Clinic and other areas. I’m glad you plan to dedicate an episode to this topic in your upcoming series.”

God forgive you, Yared. I have been writing and speaking for more than three decades—but the PFDJ has monopolized the media and chatter circles so much that it has delegitimized dissenting voices. It’s obsessed with partisan narration that it magnifies. That is what free voices have been suffering from for too long. Even the feats and struggles of the ELF are appropriated by the PFDJ, and the result is it insinuates even significant events do not mention the ELF—for example, see Tefay Haile’s comment above. He is misinformed; the ELF combatants and their commander, the late Hamis Mahmoud (first left), are denied recognition.

Until a few months ago, I mistook Yared for a different person; I’ve corrected that in the video linked here. I apologized for that, and I am doing it again.

Yodit Zack commented, “This is truly fascinating—it’s remarkable to hear from individuals who witnessed and took part in such pivotal moments of Eritrean history.” She asked about Downey, Roberts, and Jerome (the French journalist), who covered the story first, how they interpreted the events, and if any of them are still alive today to share their perspectives. She also asked why I was “heartbroken regarding the Khartoum unity meeting” when I met Petros Solomon and Ali Sayed Abdella.

I will elaborate on all of that—I feel obliged to share what I know. Thank you for your interest in history and for highlighting the dilemma of our misinformation and multiple national narratives. I sensed my audience’s eager appetite for history; I will try to satiate it to the best of my memory and knowledge.

The Story of the Picture

The photo was taken at Adi Teklay, Hamassen. It may help to know I was the translator for the journalists and the late commander, Hamid Mahmoud. And I was present the day the picture was taken, the moment the American personnel arrived. That’s when Gwynne Roberts and Nicholas Downey decided one of them must rush to Khartoum to dispatch the film reels to the BBC in London. Roberts carried the bulky film canisters and immediately headed west to reach Khartoum fast. About a week later, I heard his report on the BBC.

They had travelled on foot from Sudan to the Eritrean hinterland. The ELF had no efficient transportation at that time. A Frenchman, a photographer named Jerome whose last name I couldn’t remember, was part of the team. I met them in Hamassen and accompanied them during the second half of their journey.

The Infatuation with Kebesa (The Highlands)

In the second decade of the Eritrean struggle, combat operations shifted to Kebesa, the Eritrean Highlands. Those assigned there developed a sense of pride (bordering on arrogance). Naturally, the younger fighters wished to be transferred to Kebesa to prove their mettle!

It was in such circumstances that the late Melake Tekle sent me on assignment to Kebesa to deliver letters to senior cadres of the ELF—appointment letters based on decisions made at the 2nd Congress and the like that I don’t know about. The consignees of the letters included senior officers like the late Hadish Weldegergish, the late Mahmoud Qudwa, Osman Abdulkadir (my default commander), and others like Gebray Tewelde. Very limited radio communications existed; messages were carried by combatants in the form of letters that must be hand‑delivered.

I walked from village to village looking for the consignees, and it took me months. But the journey was rewarding—I had an opportunity to know my people and the countryside more deeply. As a relatively new combatant, I felt more exposed to Eritrea than many veterans. I felt good pretending to be a veteran. No one treated me as a novice; I didn’t experience belittling or condescending attitudes. And furthermore. I had earned the right to boast about the areas I covered and the villages I visited.

Finally, after delivering the last letter, I reported to Osman Abdulkadir in Seharti; his family’s lovely house had become an operations room. A stream ran by the side of the house—ample water for daily baths, and the people of Saharti spoiled us.

While there I met a worried farmer whose cow was infected with skin disease, Abeq, and I helped cure it!

The BinAmretay QolAa

As a little boy, I saw wood‑sellers in Keren smear their camels with “Olio Brusciato” (burned motor oil) to cure their animals of skin disease. I told the man with the diseased cow to get “olio brusciato”—not from Seharti, but to smuggle it out of Asmara. The next day, he brought a jerrycan filled with burned oil from a mechanic. It was enough to smear all the cattle in the village. We smeared his sick cow with it and, in a few days, the Abeq disease was gone. Somehow, I became as famous as a veterinarian. The villagers were amazed by the “miracle medicine” prescribed by me. “The BinAmretay QolAa” (the Beni‑Amer boy).

Maybe because of my unusual Kerenite accent and my long hair that spread over my shoulder—something the Beni Amer are known for—they called me a BinAmretay boy.

If General Teweldeberhan of the TbaH‑TbaH fame was from Saharti, God forbid, he would have argued I was not one because I lacked the tribal marks (bTaH‑bTtaH) on my cheek. I wouldn’t have the fame I earned in beautiful Seharti.

What’s next?

In the next episode, Negarit 350, we will remember my late friend Gebreberhan Zere’s role in my story and how I found myself in an interview translating in several languages, followed by the story of Canberra bombers and the days of three potato rations in Hamassen.

Awate Forum