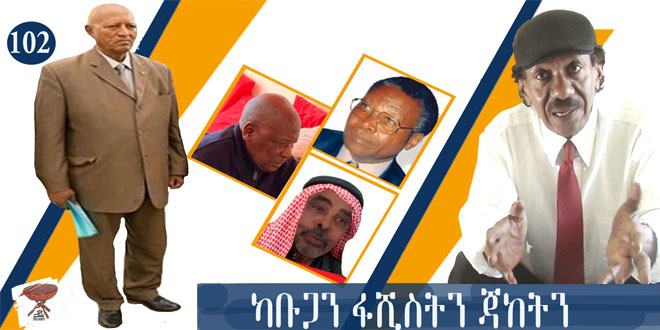

Negarit 66: ኸሊፋ ዓብደላ Khelifa AbdeAllah الخليفة عبدالله

In the end of November, a serious injustice happened in many parts of Eritrea, mainly in Seraye region. Like before, there was little coverage… and interest. Many people were arrested without charge, as usual, and pushed to unknown prisons. Of course, the victims were Muslims whose ready-made accusation is extremism. However, an extremist regime is not qualified to pass judgement on violations it has perfected.

Eritreans Muslims, mostly of the Sufi persuasion, continued to celebrate their holy days, despite a fringe that objects to anything that was not practiced a millennia ago. But the regime uses, such differences as a reason to arrest people and it did arrest many. This time, it prepared the ground by issuing a statement on November 28, accusing Qatar of planning to destabilize the Eritrean regime rulers. Appeasing its sponsors comes at the expense of the Eritrean people.

Of the many who were arrested, so far we only have the names of a few of them.

1. Nesredin Ahmed (aka: Melit/bald); Mendefera; Owner of Mendefera Plastic Bottle Factory.

2. Beyan Abdela; Mendefera; Owner of one of the biggest bakeries in the town.

3. Mahmoud Mantay; Mendefera; works at the Zonal Finance office

(NB: His brother was also arrested years back & disappeared without trace)

4. Abdelkadir Juhar; Mendefera; Chair of Mendefera Association of Fruit & Vegetable vendors.

5. Hamed Imam; Mendefera; Store keeper at Mendefera Association of Fruit & Vegetable vendors

6. Semir Safi; Mendfera; youth

7. Adem Eshete; Meraguz, from the village of Adi-Qoray

8. Berhanu Siraj & his brother

9. Mohmmed Nur Siraj; Meraguz, from the village of Adi-Gedesho

The Eritrean regime is totally inimical towards anyone who runs a business. It doesn’t want competition and runs to milk business people of their property and businesses. That is why the investment and economic activity in Eritrea is appalling. And its hordes celebrate whatever it shows–AutoCad models of planned home development every season to intoxicate the naïve among its supporter. Nothing happened so far.

First, arresting anyone for their faith, unless there is a clear violation and a charge, is objectionable. The regime should not get involved in the affairs of religious institutions like it was doing for the last four decades.

An elected, legitimate regime arresting a citizen is quite normal. That is because a proper charge, arrest, trial, and sentencing follow. But an illegitimate regime arresting people at whim with no charge has no validity. It remains, and illegitimate action supported by the security forces’ muscles. We cannot ask for a trial because the regime has no justice system, but has perfected brigandage and gang rule. Therefore, the arrested should be freed.

And that brings me to what I have been talking about in the last few episodes. True, it’s painful to see that the Islam we knew in Eritrea is damaged, corrupted, and abused and has made Muslims easy prey of victimization. But it’s upon us to reject and resist the incursions on people’s freedom of choice and an imposition of edicts that borders on sectarianism. But today, I will give you a glimpse of Islam in Eritrea, the Islam I know, through the story of “Abeshay And The Saddle Maker.”

Abeshay And The Saddle Maker

I didn’t have a chance to see my grandparents, neither from my mother’s or father’s side. However, I knew all four great-grandparents on my mother’s side: Khelifa Abdella Mohammed ANur and his Wife Saadia. Until I left Keren, my main religious influence was from them. And here is a part in my book “Of Kings and Bandits”, that sheds light on that influence.

I grew up in the main street that leads to the Mirqania compound, the Sufi leaders of most of the region’s Muslims. When I was growing up, the patron of the Sufi sect was Siddi Abdullahi AlMurqani—I was not fond of his leadership qualities but he remained a symbol of cohesion in a beleaguered nation and the Mirqani compound remained a place of spiritual venue where Muslims expressed and celebrated their identity. Here I will present you a sample of of the Eritrean Muslim– great-grandfather hoping through his description you will be able to know the qualities of the Islam and the character of a Muslim that we revere.

There was a kid named Mahmoud on the way to my grandparents’ home and he will always ask, “Where are you going?”

“To my grandparents’ house,” I said.

“Why do you go to people’s houses during lunch time?” Mahmoud asked.

“It’s not people’s house but my grandparents’!” I replied.

“They adopted your orphan mother; they are not her real parents.” Mahmoud said.

“You are jealous because you don’t have a grandfather,” I said to him as loudly as he could and walked on. I knew that got into Mahmoud’s nerves.

“Mine were young, not old and wrinkled like yours,” Mahmoud said defensively.

“But they are dead.”

I hoped that would stop him, or even make him cry. But that would not be Mahmoud.

“Abeshay and Khelifa will die soon. They’re old,” Mahmoud said, grinning and feeling vindicated.

I opened my mouth to say something but couldn’t find the right words. They will die? The thought scared me. I felt defeated with the last comment that Mahmoud hurled at him. What if they die?

I found Abeshay picking cotton from her trees when I entered to the yard. The thorny tree seemed to fight back and didn’t give in easily. I saw scars and blood droplets on her fingers. She sucked her fingers hard and spit out the red stained spatter a few times until the wounds clotted. I thought God couldn’t have created anyone darker: ivory black skin that glistened even under the shade. She had the whitest teeth, all intact. Abeshay looked like a walking divine painting: sharp, contrasting colors of bright green dress and red headscarf. The bright white cotton in her hands matched the white teeth, and the red blood droplets on her fingers melted into her dark skin.

Moments later she went to the kitchen and brought me a slice of musemmen, a sweet butter bread, on a colorful straw plate and sat on her stool. I had hoped she would get me some dried meat stew; it seems she didn’t cook any that day.

As usual, I cut a piece of the bread and said “Bismillah,” in the name of God, before putting the food in his mouth—she would make me spit a mouthful if I didn’t declare Bismillah before eating anything.

“Your food would be like poison without the blessing of God. You will never be satisfied, even if you ate a cow!” she reminded me.

Spinning cotton absorbed her. As if meditating, joy radiated from her smiling face and she hummed a song as she indulged in the art. She trained her eyes on the distaff and moved her left hand up and down, pulling swabs of cotton and feeding it to the spindle that swirled with amazing speed. The handful of cotton swabs became thinner as she rolled the spindle methodically feeding it with more cotton. Her right hand rotated the spindle and the yarn thread rolled and took the shape of a cone as the yarn wound around it. Once she had made enough, she would take it to the neighborhood weaver to make a gabi, a tunic. In gabi Abeshay found an excellent gift; she had one made for almost every relative that got married.

My Great-Grandfather’s title, KHELIFA, HAD ALMOST REPLACED his real name. It was bestowed on him by the patriarch of the Mirqani family years earlier. Since then, people had dropped his name and called him by his title because they knew him to be worthy of it. He always donned a khaki safari jacket, a thin white gabi and stooped as he walked with the support of his cane that touched the ground in a harmonious slow sequence with his feet. Khelifa seemed to be looking at his shoes as he walked, the hunch of his back showing his age.

The top of his orange kuffia—the skullcap—stood visible from the center of his white turban like an arched cone. A bushy gray beard covered most of his face. His long mustache, unidentifiable from his white beard, buried his mouth underneath. Everyone in town took notice when he passed by and greeted him with respect while the young raced to kiss his knees. To me, Khelifa resembled Moses, the prophet.

Bakri once took me to the cinema house to watch the Ten Commandments, a movie like all others, dubbed in Italian. Moses and his people spoke in Italian; Khelifa also uttered Italian words if something annoyed him. I wondered if Khelifa might have come from that age. He could have been the twin brother of Moses.

Officially retired, Khelifa refused to stop working. He continued making saddles and sandals until a few months before his death. In a town with only two or three horse owners, I wondered where the saddles went.

Khelifa regularly led prayers in his neighborhood mosque for years; so devout in observing his religious duties, he wouldn’t miss a prayer time for any reason. A bulging black callus growth on his forehead attested to his frequent praying. At home, he spent most of his time reading and re-reading his old books. Daily, his forehead touched the ground in postulation thirty-four mandatory times, fard, and probably as many voluntary extras, Sunnah. Thus, he acquired an almost mythical status. I never heard him complain, raise his voice, gossip or mention anyone with contempt. He enjoyed telling me the stories of the prophets. Often, he would mention stories of the saddles he made for the cavalry forces before going back to the stories of the prophets.

I would ask him, “How could someone stay alive inside a fish?”

“It is not a fish, it is a hoot, a very large fish,” Khelifa said.

“How big is it to swallow a man?”

“Very big.” Khelifa explained, “It can swallow several men.”

The story of a person staying alive inside a fish baffled me; the existence of a fish that large mystified me. I couldn’t help admiring Jonah more than Moses, who looked like Khelifa.

“But Younis didn’t die!” I doubted the story.

“No. It didn’t bite or chew him, just swallowed him. It is a miracle, a Will of God,” Khelifa said blocking any further argument.

Once the Will of the almighty God is invoked as an explanation, questioning the logic is not encouraged–-I had always known that. I nodded pretending to have accepted the story, still questioning the possibility of someone coming out of a whale’s stomach alive.

I tried hard to understand the story of Jonah, but Khelifa added more to my puzzlement by mentioning another fascinating story. “Divine miracles. Eissa had the power to cure the blind and raise the dead.”

“He did?” I had asked with his eyes staring at the cup of water on the table, attempting to visualize the size of the body of water needed to accommodate a big fish that could swallow people. Then I tried to imagine someone walking on it.

For the first time I had seen a large body of water and flood in the movie, The Ten Commandments, where I also saw Moses. But children told me what he saw is not real, but Sehr, magic. Yet, I wondered if Younis actually made it back to the shores.

“Did he have wounds when he came out?” I asked

“No. Not a scratch,” Khelifa said.

“Is must be a big water, like the one Mousa made disappear?” I asked.

Khelifa stared at him. He looked even more like Moses. “You remember the story of Mousa!” he said with a smile.

“I saw it disappear. I saw the men with swords chasing Seyedna Mousa,” I explained trying to remember what else happened in the movie so that I would recount it to Khelifa.

“It happened thousands of years ago; you must have dreamed about it,” he said with a chuckle.

“I didn’t dream it. I saw it in the cinema with my father,” I said.

Khelifa’s face stiffened. “Cinema! That is the work of Sheitan. What do cinema people know about Mousa?” Khelifa said disapprovingly.

“There was no Devil, I didn’t see one!” I explained

“I will talk to your father; he shouldn’t take you to the cinema,” he said with a brief smile. I could tell Khelifa was not happy with my father; he started to murmur some words in Italian. Sensing his displeasure, I changed the subject, “Who is older, Mousa or prophet Mohammed?”

“No, prophet Mohammed is very young. The era of Mousa was a long, long time ago.” He said waving his hands over his shoulders as if trying to push time thousands of years back.

In one of the campaigns in a remote mountainous region, Khelifa observed the tattered harness of the pack animals. He treated a fresh bull skin with a mixture of salt and ground barks, and after a few days, he made new harnesses for the mules. His commander was pleased and transferred Khelifa to the stables of the cavalry units in Keren. In a short time, he began to make impressive saddles and shoes. He gained acclaim for his workmanship. Decorations, a pay raise and medals followed.

Simahom fi wjuhihim mn ather a’sejoud (You see their piety in the their faces due to prayers)

WHEN THE CALLUS ON HIS FOREHEAD GREW back every few weeks, Kehlifa sat on his wicker chair while Abeshay stood in front of him like a barber shaving a customer’s beard. She scraped the dead cells off his forehead with sharp razor blades while he enjoyed his moist tobacco until she finished performing the task as carefully as a work of art.

Sometimes, Khelifa couldn’t bear the boredom, sitting with his head facing the ceiling. The tobacco still in his mouth, he fidgeted with his prayer beads and gargled something under his breath. Only Abeshay fully understood the gurgling sounds. I could make sense of a few words that sounded like, “are you done yet?”

She calmly responded, “Patience, I am almost done.” Then she went a few steps back and squinted focusing her eyes on his forehead to see its smoothing. Often, discovering some parts that needed more scraping, she said, “A little more there,” and worked on the callus surface with the exactness of a plastic surgeon. When she finished, Khelifa thanked Abeshay, “may God reward you.” He then went to spit out the tobacco-stained strand of brown spittle and cleaned his mustache with a handkerchief. Then he prepared himself to go to the mosque for more prayer.

Whenever I walked to Khelifa’s room, he always found him reading from a book on his lap. I stood by the side silently until Khelifa folded the book, leaving a book-marker where he stopped. I then kissed his knees and said ‘Ameen’ as Khelifa showered me with blessings, always sensing the smell of tobacco coming out of Khelifa’s mouth as he kissed my forehead and hugged me. Then I sat beside Khelifa as he resumed reading loudly in an enchanting voice, moving his head and shoulder, in a rhythm like a pendulum. Sometimes, he seemed to go into a deep trance, totally absent from everything around him. A few times I found him reciting emotionally, with tears flowing down his cheeks. He said, the love of God, and at the same time the fear of God, made him cry.

When I asked him when he was going to finish reading the book he laughed. Then he took out his chained clock from his pocket, glanced at it as if he was on a timed reading, and casually said, “You never finish reading the Koran.”

Khelifa had just a number of huge books, bound in what might have been expensive felt cloth of different colors before turning yellowish with time.

“You read the Koran. You finish it. Then re-read it again,” Khelifa had said. “I memorized the Koran as a child, and I have been reading it ever since. I will continue reading it until I die.”

I didn’t like the mentioning of death casually but nodded anyway.

“Lies, back-biting and gossip take you to hell fire,” he warned and looked up as if talking to the ceiling, “Oh God forgive our sins.”

“Who lied?”

“No one. Idle people talk nonsense and make mistakes. Reading the Koran prevents one from that and cleanses the spirit,” Khelifa said, “You shouldn’t mention people who are not present to say their side in a conversation. May God forgive us.”

Khelifa lived a predictable, routine life. He woke up at dawn, sipped coffee and walked to the mosque along the rocky, eroded dirt road rolling his beads and praying in a whisper. Afterwards, he returned to his house, ate a quick breakfast, donned his Safari jacket and white robes and went to work. After work, he came home and stayed at home, reading until minutes before sunset when he went to the mosque again for the evening prayers.

Awate Forum