History is Watching us

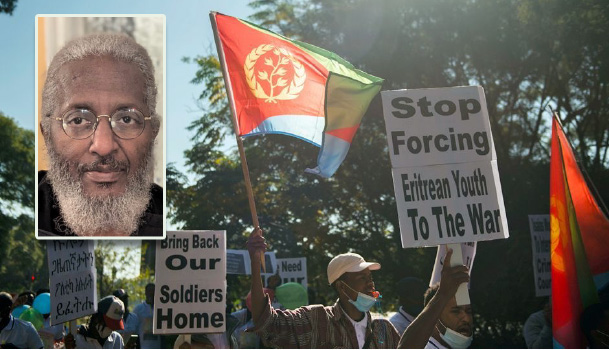

[This article is dedicated to a group of Eritrea’s Prisoners of Conscience who were arrested in 2001 after criticising President Isaias Afwerki’s rule, and have never been seen or heard from since. The prisoners, rather selflessly, led the way to meet the challenges head-on while their fellow ex-freedom-fighters failed to follow suit .]

This piece coincides with the death of Eritrea’s former finance minister, Berhane Abrehe, who died in prison this year. It is to be remembered that he was arrested on 17 September 2018 after he published a book which, among many other issues, pleaded with his fellow freedom fighters to protract the campaigns on behalf of former colleagues – Eritrea’s prisoners of conscience.

His plea resonated with me for I ended up connecting with it on a deep and personal level. Leaving its personal imprints aside for now, allow me to reiterate the fact that Berhane Abrehe’s testimonial was a strong form of protest against President Isaias Afwerki’s autocratic rule.

He intrepidly took the opportunity to protest by raising his voice for compassion – a voice that is still rumbling in people’s hearts, minds and in the Eritrean wilderness.

I believe level-headed Eritreans are with him in spirit – they are of the opinion that they have the duty to speak out and protest on behalf of the long-suffering citizens of Eritrea.

I would like to take the above mentioned assertion to a higher degree by arguing that there exist constellations of ex-freedom fighters in the country who are poised to extend Berhane Abrehe’s appeal provided they get their act together.

Those various clusters of ex-freedom fighters are the best suitable units of change. They can unleash the power of their communities to solve Eritrea’s problems as our people need them to act at a level to improve real life outcomes now. If truth be told, they are their Brothers’ Keepers.

Was it Martin Luther King, Jr. who said ‘He who accepts evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it’? Knowing full well nobody wants to be blamed for cooperating with evil, the former freedom fighters whose conscience might be giving them a nudge to act – before the miserable life in the country unfolds into an utter nightmare – are certainly at a crossroads now. Of course, shouldering the responsibility of protesting inside Eritrea in order to counter the regime’s stranglehold on the downtrodden citizens of Eritrea is challenging.

However, having stated the central premise of my argument, allow me to proceed to state that protests are not only challenging but doable in Eritrea.

In the West Eritreans have a right to protest peacefully, and host nations have a duty to respect, facilitate and protect this right. In Eritrea themes surrounding protest is a totally different story.

Let’s revisit a series of protests that occurred in Eritrea in order to contextualise the ins and outs of my assertions.

In spite of the fact that protests are prohibited in Eritrea, there have been many protests that had shaken the government over the years. Often the protests are remembered by ‘the June 1993 protest’, ‘the July 1994 protest’, ‘the August 2001 protest’, ‘the January 2013 protest’, ‘the October 2017 protest’ and so forth.

One has to admit that although the above mentioned protests made a dent in the regime’s armour, they failed to maximise the outcome because, as the saying goes, victory is seldom won by half measures.

One has to admit that real change has eluded the protesters all along. Many of us have reflected on how momentum can be sustained to bring about lasting change in Eritrea.

The government views protests as illegal undertakings and clamps down on protestors rather heavy-handedly – with arrests and torture. From time to time reports reach the public regarding the fate of protesters – that they were covertly picked up and made to disappear by the country’s CIDs. Nevertheless, protests continued.

This article is based on protests in Eritrea that Dan Connell presented in his seminal book – Historical Dictionary of Eritrea.

The June 1993 protest, known as the ‘Fighters’ Uprising’

On June 20, 1993, four days before the referendum was concluded and independence was officially declared, the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) fighters staged the largest mass protest against the revolutionary leaders.

The sudden uprising immediately paralyzed the city of Asmara and led to the closure of Asmara airport. It is to be remembered that the incident left the guests who flew in to attend the Independence Day celebrations in limbo.

The protest erupted two days earlier when Isaias Afwerki (who was not president at the time and was named president by the Provisional National Assembly on June 24 under questionable circumstances) said in a speech to the EPLF Central Committee that fighters should serve (without pay) for another four years.

The striking ex-fighters reacted out of frustration because they could not help their families who were in extreme poverty, and were not in a position to contribute towards the recovery process of the country’s economic woes. The combatants had roamed in the wilderness for so long – some for more than twenty years – their repressed aggravation ripped open to reach onto the streets of Asmara when Isaias placed more burdensome demands upon them.

Connell stated the protests began at the airport early in the morning. As aeroplanes were banned from landing and taking off, the news spread quickly among the EPLF units by radio.

Among the most prominent dissidents were young fighters who attended ‘School Zero’ during the armed struggle and continued their contacts after independence.

Within hours, armed fighters took control of banks and government buildings in the city, and strangled traffic in Asmara. Members of artillery and tank units joined them.

Army officers and members of the political bureau, as well as Isaias Afwerki himself, were rejected when they tried to approach the demonstrators. The protesters demanded that their grievances be heard in public.

In the afternoon, Isaias agreed to meet with the protesters at the city stadium.

When he arrived at the stadium, he sweet-talked his way back into their affection by promising them a new salary schedule and discharge benefits.

He also said that 50 million Ethiopian birr ($7 million) will be allocated to projects for veterans and war victims and their families.

His promises and his friendly manner lulled them into a false sense of security. On that very night Isaias appeared on state media to denounce the protest as “illegal” and the protesters as “infantile”. Two days after he craftily quelled the unrest, he proceeded to pick up more than 200 ex-fighters who took part in the rebellion and those who allegedly organised it. They were imprisoned for two years without trial.

Some of them were released, while others – presumed as leaders – were sentenced to 12 years in prison,” Connell wrote. “And some of them were ordered to return to their units only to learn they were deprived of their small pocket money and annual leave,” he added.

The above paragraphs are excerpts that summarise the June 1993 protests. The other protests have their own causes and rationales. But at the centre of the dispute has always been the unelected leader – for the way he kept forcing himself on Eritreans.

There were other confrontations in the battlefields of Eritrea before the liberation struggle was concluded. For example, two movements that are frequently highlighted in history books are that of ‘MenkaE’ and ‘Yemin’, both directed against Isaias.

The ‘MenkaE‘ and ‘Yemin‘ movements

‘Menka’ was a movement that primarily resulted from and intertwined within the ‘Ala Group’ – or what was known as the ‘Freedom Party’ which was led by Isaiah Afwerki.

‘Menka’ was launched by Mussie Tesfamichael, a classmate and close friend of Isaias (when they were at Prince Mekonnen High School in Asmara). He was accompanied by Tewolde Eyob and other prominent members of the emerging Front. It occurred during 1973-1974.

Members of the movement were mostly left-wing. They demanded democratic decision-making and Marxist social programmes to be introduced. Historical documents show that they advocated for the rights of the fighters to be respected, and accountability of the leaders. They were also said to have strongly criticised Isaias for his dictatorial tendencies.

They were summarily executed.

The punishment the ‘MenkaE‘ group received for their ‘crimes’ should have been in proportion to the severity of their crime itself; they only launched a democratic challenge to the status quo; Isaias’ ways of handling matters that affected combatants’ existence. They did not perpetrate an assassination attempt of their leader; they did not conduct undercover work for the enemy. Were they engaged in espionage? No, they wanted to introduce internal reforms that relieve their fears and anxieties.

‘Yemin‘ was a movement that arose within the EPLF fighters from the mid-to-late 1970s. It was associated with Solomon Woldemariam, the party’s internal security chief who played a role in the suppression of the ‘Menka’ members. Solomon was also said to have played a major role in the early formation of the EPLF.

Although the leaders of the EPLF stated the ‘Yemin’ movement was a right-wing movement, critics describe it as essentially an anti-authoritarian movement, with neither right-wing nor left-wing tendencies.

Yemin‘s fate, like most of the MenkaE members, ended in assassination. Solomon was executed in the early 1980’s.

The Mayhabar Protest

It was July 1994. It was a time when many disabled fighters in Mayhabar – a care centre for the war-injured – were protesting stridently.

Mayhabar is located 25 km east of Asmara. The former war veterans who had taken refuge in Mayhabar had formed an association called the Eritrean War Veterans Association. On July 11, 1994, having been concerned of the rumours they heard – that they would be moved from their base involuntarily – they came together and left for Asmara to protest against the planned move publicly.

When ordered to stop before they reached Asmara by armed police units, they took Amaniel Mihret Ab, the director of Deployment Office, and his second in command as hostages instead. They insisted that they would proceed to Asmara to express their grievances to senior government officials.

Since President Isaias Afwerki was in Uganda at the time, Abrha Kassa, the head of National Security, took over the case and sent armed commandos to prevent the protesters from reaching Asmara.

Armed commandos confronted the protesting disabled fighters near Nefasit and opened fire on them. Several of them were killed in the shootout. Then the protest was dispersed by government’s response which was wholly disproportionate.

The public witnessed the event; Eritreans living abroad condemned the cruelty; and the incident was covered in world media.

The leaders of the protest like those who had participated in the May 1993 protests before them, were all arrested and languished in prison.

More cases of Protests

Among the other memorable public protests was the one associated with Semere Kesete Negassi, the former leader of the Asmara University Students’ Union. After Semere spoke out against injustice he was unjustly arrested by government agents. About 400 students marched outside the Supreme Court to demand his release. Historical documents show that the students who protested against their leader’s incarceration were rounded up and sent to Wia, a work camp in the coastal region. To be brief, Semere’s story had a different ending – he escaped from prison and was able to seek asylum in exile.

The 2001 protest conducted by the G-15 (Group of 15) was unique in the history of Eritrea. It exposed one of the biggest travesties of justice in the country. The G-15’s ‘crime’ was their boldness to demand that it was time to hand over power to the people.

BTW, several of the members of the G-15 were founders of the EPLF.

As mentioned in my intro, it is to be remembered 23 years ago, on 18 and 19 September, six weeks after their Open Letter was published on local papers, 11 of the 15 signatories were not only arrested but they were made to simply disappear off the face of the earth.

It was mere luck that three were out of the country at the time. And one had recanted (and was spared incarceration; and later he went into exile). The three who were not in the country during the round up, one died of illness years later, and the other two are living in the West.

The disappearance of the top government officials and revolutionary leaders who participated in writing the ‘open letter’ has led to condemnation of Isaias Afwerki and his regime by the international community, human rights organisations and others concerned.

Many Eritreans concluded that the president’s cruelty emanated from his vindictive nature. One can say he is suffers from delusions of personal greatness and grandeur, and he is spiteful towards those who do not owe total allegiance to his rule.

The ‘Wedi-Ali’ and ‘Haji Musa’ Protests

The biggest protest of them all was the failed January 2013 coup d’état led by Colonel Said Ali Hijaj, ‘Wedi-Ali’, commander of the mechanised brigade in Tserona.

When the units assigned to join ‘Wedi Ali‘ in the revolt were somehow delayed for unknown reasons, the attempted coup came undone. ‘Wedi Ali’ reportedly committed suicide when he was surrounded by government soldiers.

A few years after ‘Operation Forto’ was foiled, Haji Musa Mohammed Nur died. It was October 2017. Haji Musa was a respected and valued member of the Muslim community of Eritrea. He protested when the government pressured him to close the Muslim school he was running in Akria, located at the Northeast of Asmara. He was later arrested at the age of 93.

After his arrest his followers and supporters held peaceful demonstrations for his release. The protesters were beaten with force and brutality by government soldiers until they were disbanded. Haji Musa Mohammed Nur passed away in prison on March 1, 2018.

To make a long viewpoint short, the above mentioned protests demonstrate that one can protest inside Eritrea.

Future Protests

President Isaias Afwerki’s regime will continue to face future protests as long as he remains in power.

Some of the future protesters will be conducted by clusters of the ex-freedom fighter-community. They will have to pluck up some courage to induce change with a sense of national duty to redeem their history and to make up for the suffering they caused to the people of Eritrea.

Therefore, I would like the ex-freedom fighter community to pay heed to the following staccato cautionary messages because history is watching them.

- … You have the prerogative to put things right because you are the ones who brought Isaias in and put him in power without our consent.

- You propped him up as you eagerly waited to become the beneficiaries of government jobs.

- You watched him from the side lines as he manipulated history, one that you were part of, to serve his own agenda.

- You did not raise a finger as he designed the current system with your help in order to preserve his interests and authority;

- You remain unresponsive to his master plan in which you have no role whatsoever.

- You did not react when he systematically ‘froze’ you and motioned you to leave the country;

- You chose to ignore the Open Letter your comrades wrote to you as you simply rolled with the punches.

- If Berhane Abrehe dared to go into the lion’s den to accentuate the case of the prisoners of conscience so can you.

May this anniversary inspire you to rectify the situation on the ground and restore our martyrs’ promises!

Awate Forum