Eritrea’s Feigned Longing for Peace

President Isaias Afwerki sealed border crossings not only because the outflow of Eritrean citizens to Ethiopia intensified, but peace, generally speaking, is not working for him.

Bestowing the prestigious Nobel Peace Prize on PM Abiy Ahmed while leaving out his counterpart, President Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea, was a noticeable insult from which, ostensibly, the Eritrean regime and its supporters have not recovered yet. Why was the Eritrean president snubbed by the Norwegian Nobel Committee? Was it because the committee could discern that Eritrea feigned peace?

Activists, civil societies groups, opposition groups, analysts and many others expressed their views regarding the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize that was awarded to Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia. Many sent congratulatory messages to the PM for his initiative to bring peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea, while others were not convinced whether he really deserved the ‘half-baked’ nature of the peace agreement. In any case, the whole world talked about the prize except Eritrea.

Yes, there was not a single story published on government papers regarding the Peace Prize. Haddas Eritra (Tigrinya), Eritrea AlHaditha (Arabic), Eritrea Profile (English) as well as Shabait.com, the principal government website, and other pro-government media outlets simply ignored the story. Why?

A bit of background history

The Peace Prize is a major victory for the charismatic Ethiopian premiere who dared to annul the 17 year old stalemate between Ethiopia and Eritrea. In 2018 he declared he would honour the UN ruling of 2002.

It is to be remembered that the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission was established pursuant to the Algiers Agreement of 12 December 2000 between the two countries; and then it reached a verdict a year later – a verdict that was final and binding. In spite of that, it had been repeatedly rejected by Ethiopia until PM Abiy Ahmed came to power in 2018.

The two previous governments of Ethiopia – that of the late Meles Zenawi and Hailemariam Desalegn – refused to honour the verdict while resorting to quiet, punitive measures against Eritrea which went on for far too long.

The Punitive Measures

The primary punitive measure Ethiopia applied was by stalemating the resolution which caused a state of lingering tension between the two countries. The tension caused enormous damages to Eritrea’s economy while Ethiopia continued to enjoy relative progress. For instance, Ethiopia built universities and other institutions of higher learning during the stalemate period; and the country managed to produce tens of thousands of educated youth. On the contrary, Eritrean students received mediocre education and the majority were relegated to do forced manual labour via the National Service programme.

The state of tension gave the Eritrean regime a pretext to rule as it pleased; as if the country was in a state of emergency. The regime dodged demands to introduce reforms, continued with its open-ended national service, denied citizens space to operate freely, and prevented the youth to live a normal life.

The second punitive measure was designed to isolate Eritrea. As Ethiopia was the darling of the international community, it successfully rallied its supporters to mete out UN sanctions on Eritrea. Eritrea was allegedly accused of arming terrorist groups in the Horn region. The sanctions, subsequently, prompted Eritrea to stick to its hollow ‘self-reliant’ programme which in turn put a tighter stranglehold on the country’s economy.

Basically, the regime used its ‘self-reliance’ policy rather illicitly. It misappropriated small businesses, plundered national and institutional resources, exploited the labour force and more in the name of ‘self-reliance’.

The third punitive measure was carried out through the pull/push factors in the region. Ethiopia created a condition for the pull factor that enticed Eritrean nationals to flee. And Eritrea, of course, played its part by pushing its own citizens out. The stifling situation in the country became too unbearable for Eritreans to stay put.

The Eritrean dream crumbled as its population dispersed. Consequently, Eritrea ended up becoming one of the highest refugee-producing countries in the world. According to the UN refugee agency, Eritrean refugee numbers worldwide, 2014-18, has surpassed half a million.

It is amid this confusion and heightened youth drain that the Peace Accord was suddenly declared.

The ‘sudden’ 2018 Peace Accord

In 2018, PM Abiy Ahmed’s announcement to overturn Ethiopia’s stand, the longstanding stalemate, came unexpectedly. The change of heart was embraced and celebrated not only by the majority of Ethiopians and all Eritreans but by the international community as well.

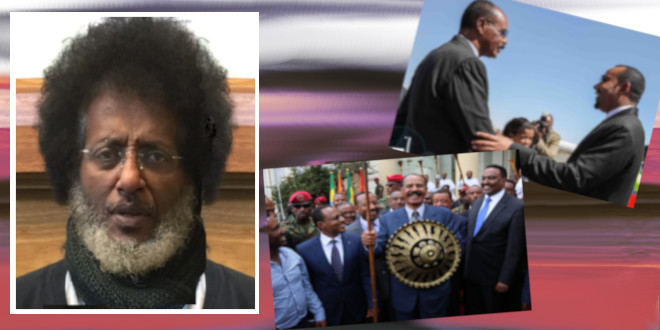

Unprecedented, the Ethiopian Premier relayed a goodwill message to President Isaias via television in Tigrinya, one of Eritrea’s main languages; and by doing so he won the hearts of many sceptics. On the other hand, the Eritrean president could not reciprocate well enough; he failed to articulate his thoughts on that historic occasion. He is remembered for his infamous ‘you lead us now’ phrase which surprised, actually alarmed, Eritreans in and out of the country, including his supporters. By that he asked PM Abiy to take charge of the peace process, and perhaps more. Furthermore, many watched with amazement as the president, uncharacteristic of his stone-cold expression, was caught on camera giggling and beating his chest with elation.

After the two leaders held a series of meetings in both capitals in June 2018, they subsequently signed a peace deal on 8–9 July 2018 in Asmara, Eritrea. It was rather a surreal experience to the citizens of both countries and international observers as the two leaders embraced and promised to end the two-decade-old state of no-war-no-peace stalemate between their two countries.

What did Peace bring to Eritrea?

As President Isaias enjoyed the newly found attention during his visit to Ethiopia, he somehow fumbled. He started walking a thin line between opening-up and self-preservation. At the same time, his supporters were still dumbfounded by the unexpected development and the shoddy ‘you lead us’ approach the president let drop. Basically, the president and his supporters were seen marching out of lockstep for weeks. Delegating the peace process to the Ethiopian premier was a bit too much for his supporters to digest. Nevertheless, one can say that hopes went soaring with exhilaration after the peace accord was signed.

Credit is due to the Nobel Prize awardee, PM Abiy Ahmed, for breaking the ice and for triumphing over that crucial stalemate. However, by holding out an olive branch to Eritrea and by conceding to Eritrea’s staunch demands, the PM ended up putting President Isaias, perhaps unintentionally, on the back foot.

Ethiopia’s sudden acceptance of the UN ruling of 2002 – Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission decision regarding delimitation of the border – pulled the rug out from under president Isaias’ feet.

The sudden recognition of the ruling meant that Eritrea could not use the state of tension between the two countries as a primary motive for arresting Eritrea’s social, economic and political developments anymore. Likewise, the logic of the perpetual entrapment of Eritrea’s youth through the national service programme was suddenly overturned by the ‘peace agreement’.

The Dictates of Exorbitant Fear

The ball has been in Eritrea’s court, so to speak, since that momentous summer of 2018. President Isaias signalled as if he was prepared to respond to the PM’s courageous move in kind. But it did not take him long to have second thoughts about the upshots of ‘peace’.

President Isaias reneged on everything he had promised to do during the signing of the peace agreement. Actually, he started dismantling people’s hopes and expectations soon after the signing ceremony.

Instead of being magnanimous and pressing forward with the ‘peace-project’ he chose to focus on settling old scores with the Tigrayans, the ‘TPLF gang’, as he used to refer to them. It was un-presidential of him to let off a lot of steam like that at that stage. Although his ‘TPLF gang’ rhetoric gradually subsided, he did exhibit his true colours then to the world at that crucial time. Presumably, the Norwegian Nobel Committee took all that into account as it deliberated to pick a worthy nominee for the award.

Soon after the honeymoon period was over, the president began to re-assess the situation more vigilantly. He saw more and more Eritreans were fleeing to Ethiopia and others were directly engaging with Tigrayans positively and without any inhibition through trade – an act the government quickly frowned upon. In Eritrea the PFDJ, the president’s party, is the sole owner of and player in business activities.

The new era signalled that his self-preservation policy came in direct conflict with opening-up the country to Tigray/Ethiopia. That alone made him realise that peace comes with a ‘cost’, to his regime, not Eritrea. It posed an affront to his rule by eroding some aspects of his authority; that is by opening up Eritrea to a new era of ‘peace’.

Furthermore, the president’s self-preservation ‘policy’ would be hard to maintain if he had allowed more and more Eritreans to compare and contrast for themselves the two divergent developments on his watch – Ethiopia’s advancement as opposed to Eritrea’s decline.

Paranoia sets in once again

President Isaias Afwerki sealed border crossings not only because the outflow of Eritrean citizens to Ethiopia intensified, but peace, generally speaking, was not working for him.

After the peace deal, the government realised it could not justify its rigid rule anymore. In other words, peace meant that the government could not sustain the strictly controlled existence it had imposed on the people. Yes, the government’s mantra of the last two decades – “tighten your belt and remain vigilant at any cost” – was suddenly rendered void and meaningless.

Those who managed to visit Ethiopia during the brief opening of the border had learned the government had lied to them all along. They also found out the region of Tigray, for instance, is far more developed than Eritrea; and the people in Adwa, Mekele, Adigrat and elsewhere have been, relatively speaking, enjoying a better standard of living.

As far as the president is concerned, the region of Tigray was put on a showcase during that brief period when people could cross the border freely. And it can be argued that showcasing Tigray did not bode well for the president’s puffery.

“A Leopard does not change its spots”

PM Abiy did take a gamble in reaching out to his Eritrean counterpart. But Eritrea is wavering to do its part because it is not ready for ‘real peace’ yet. Had Eritrea been seriously engaged in the peace process we would have noticed some changes on the ground by now. But nothing has changed across-the-board in the Eritrean political, economic and social landscapes since 2018. Unfortunately, no substantive work has been undertaken to normalise relations between the two countries since the signing of the Peace Accord. That leads us to ask questions about the sincerity of the peace process.

Questions that were raised soon after the peace agreement in 2018 still remain unanswered. Will the government delineate the boundary which has been the main bone of contention between the two countries for a long time? Will it reform the national service? Can the regime loosen its tight grip on free enterprise and allow Eritreans to live a normal life? Now we can confidently say that demarcation is a subject matter that is conveniently forgotten; putting an end to the open-ended nature of the national service is just swept under the rug; and introducing political reforms is simply unimaginable.

The peace agreement was supposed to change people’s livelihoods. But it didn’t. Instead Eritrea is still being governed with an iron fist and utmost secrecy. The president continues to rule as if Eritrea is his personal property. Sadly, Eritrea has become a country where events are orchestrated and its citizens are kept quiet as government officials depict false realities.

Now many are questioning if the peace accord was a sincere effort intended to put an end to Eritrea’s woes. Yes, livelihoods can be changed through peace processes only if the feuding parties stick to the terms of agreements. Let’s just say Eritrea’s case is out of the ordinary.

It would be naïve to think that Eritrea will ever honour the terms of the peace agreement because the president and his abettors are very much living ‘la dolce vita’.

For now we can conclude by saying that leaving out President Isaias Afwerki out in the cold while his ‘partner’ was relishing his moment of glory in Oslo proves that the Norwegian Nobel Committee had figured it out that Eritrea was only feigning peace.

Awate Forum