Eritrea: Language and Identity And Globalization

The article, “Abyssinia (Al Habasha): Origins and Language by: Professor JalaLuddin M.Saleh, Ph.D.” posted by Beyan Negash has generated a very good discussion on the origins of Ge’ez in relationship to Arabic. I have posted several clarification comments under the article. My assessment of the article itself comes from a limited world view but it has helped us dig deep into a lot of related issues, which I appreciate. I hope others had the same assessment.

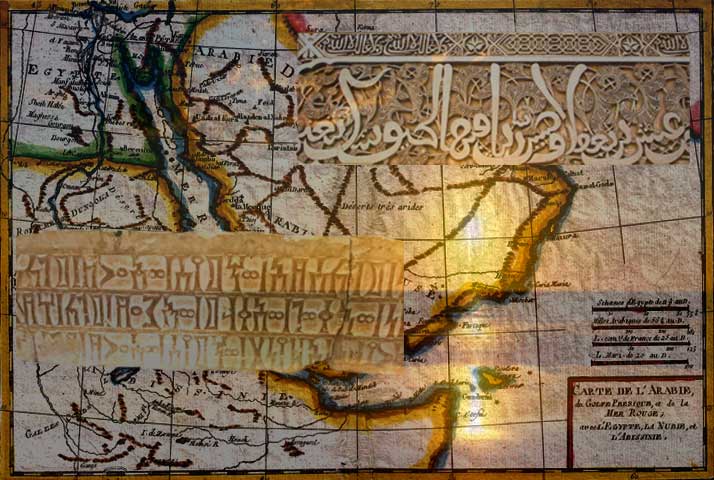

My article tries explore issues of language and identity in Eritrea. Dr. JalaLuddin M. Saleh’s addresses the origin of a dominant language in Eritrea and he tries to tie its origin or subordination to yet another dominant language and culture, which reached its zenith because of its affiliation with a dominant religious tradition. In both cases, in our area, Ge’ez (Tigrinya) is associated with Christianity and Arabic is associated with Islam. Though both came from the same origin, due their religious affiliation or as tools of different religious expressions, their differences are highlighted instead of their communality or affinity. My goal here is not to reconcile their differences but to highlight their dominance and their unfair advantage of the other minority languages in Eritrea.

The world is becoming smaller due to globalization and technology. Though Tigrinya might seem dominant in its limited environment, compared to the global trend, it is on the losing path. English, a language from a tiny British Isle is coming super dominant all over the world. Arabic in its association with Islam is trying to push back but with the religious radicalization of some of its elements, in some parts of the world it is seen as a liability instead of an asset.

Having stated that, let us go back to the rest of the Eritrean languages alphabetically: Afar, Beja, Blin, Kunama, Nara, Saho, and Tigre (Tigrayit). These seven languages, are trying to survive under a Tigrinya and Arabic dominance. The effort to use them in primary education is commendable but with increasing trends of urbanization, migration, not to mention Arabization and Tigrinyanization, these languages face the danger of extinction. For a full disclosure, I am a Tigrinya speaker, but my early exposure to Saho and Tigre did not stick because they were replaced by Amharic, English, and other languages in between. This was a regression from our parents and grandparents, who grew up multi-lingual though most of them never went to any form of grammar school. Modern education, or Western education, estranged us from our own language and culture. Therefore, globalization was creeping up for the last 70 years, starting after the end of World War II.

Globalization started in earnest with the colonization of the New World (the Americas) 500 hundred-years ago and has accelerated speed in the last 70 years and more so since the 1960’s in Africa. Liberation from colonial powers did not help African countries recapture their language and culture but Westernization became the way forward, a symbol of civilization and human advancement. When we lose our native languages, we compromise our identity. The wisdom, the knowledge, the pride and the sense of belonging is taken away from a community or individual who once had strong sense of identity and belonging.

In my assessment of Dr. JalaLuddin’s article, I tried to paint a bigger picture that the languages in Eritrea, except Kunama and Nara (believed to be part of the Nilotic family of languages), the rest fall under the Afro-Asiatic family of languages. Yet, such distant relationships cannot cloud our perspective; therefore, their uniqueness must be preserved in the words of a wise person, “Losing an ethnic language is like burning a whole library.” Are we aware of such ramifications when we give up our native language in favor of a dominant one? For example, in the case of Tigrinya, Amharic and Arabic in our area, overshadow other ethnic languages. The effort to preserve ethnic minority languages is shrugged by the dominant culture or language. For example, our discussion or reaction to “Abyssinia (Al Habasha): Origins and Language” was concerned more about dominance and prominence. Though very important issues were raised and clarifications made; giving us better perspective or context the implication of such dominance on Eritrean ethnic minority languages was absent.

Dr. JalaLuddin’s article raised a fundamental issue of identity. Who do I say I am in the tapestry of Eritrean national identity vs. other ethnic groups? Am I to accept the explanation of the article or do I have a different sense of identity supported by genealogical lineage adorned by folkloric and mythological stories? Am I to reject one in favor of the other. I had mentioned in my comments that naming oneself or others signifies power over the named. If I have the freedom to name myself, I am exhibiting my independence and power.

In the 19th century, there was a Catholic monk in his manuscript “ተሰኣሎ ለኣቡከ – Tese’alo L’Abuke – Ask Your Father” who rejected the word “ሓበሻ – HABESHA” as a derogatory word because of the implication of mixed race “ድቓል-Diqala–bastard.” He saw it as demeaning; therefore, as the title of his manuscript describes “ተሰኣሎ ለኣቡከ – Tese’alo L’Abuke – Ask Your Father”, he wanted his readers to follow the name his ancestors give to themselves and their sense of identity and belongings. For example, he preferred the word Ethiopian, a word present in the Bible. This was before the creation of Eritrea. However, with passage of time word HABESHA became accepted; in fact, a common name for Eritreans and Ethiopians, signifying neutrality and affirming common identity. Yet, such an evolution of language also led to the word Habesha to mean Christian or only Amharic and Tigrinya speakers. Therefore, instead of becoming a common name for Ethiopians and Eritreans, it ended up in hair splitting process of exclusion. According to Dr. JalaLuddin’s article, however, Al Habesha was a tribe or a clan not mixture of race the way many of us learned understood growing up.

In Eritrea and in the Horn of Africa in general, one cannot be accurate about ethnic purity or identity because people claim multiple identities. We can be more accurate of language affinity than ethnic identity. As in my favorite Ge’ez proverb, “በሰመ ሓዳሪ ይጸዋዕ ማሕደር በስመ ማሕደር ይጸዋዕ ሓደሪ – a dwelling is named by the dweller, a dweller is called after the dwelling.” Many Eritrean genealogists tell us that family lineages cross language, ethnic and religious lines. As our ancestors correctly tell us, “ወለዶ ሓረግ’ዪ – genealogy is like a vine tree (intertwined/interconnected).” If our national and regional identity is interconnected by blood and language, then it behooves us to be concerned about the survival of ethnic minority languages in Eritrea and in our region in general.

Tigrinya is coming with a competitive advantage over other Eritrean languages because of the urban locations as well as because of its scripts. Arabic though limited to Rashaida as native language, religious affiliation with Islam tends to play dominant role at the expense of local languages in Eritrea and other parts of the world where it tends to have great influence. If some Eritreans have negative attitude towards Arabic language, it is fear of cultural domination through Arabization not the Arabic language on itself. This negative attitude towards Arabization is not limited to Eritrean Christians but other Eritrean ethnic groups, who are Muslims too. For example, in the last forty-years, Arabization came with religious puritanism, affecting traditional ethnic practices, cultural norms and customs, including dressing up like Arabs; abandoning millennia old ways of life that do not contradict religious practices.

I would not be happy to see my Tigrinya culture suffocating other Eritrean ethnic group languages and their way of life. That would be another form of cultural domination akin to colonization of culture. During Emperor Haile-Selassie’s era, the practice of Amharazation caused the current government of Ethiopia to react to the other extreme by creating federal states based on language and ethnic affiliation. This is good in a way for cultural and language preservation. Balancing national unity with ethnic/language identity is delicate process requiring policy skills and maturity.

In grand schemes, there is bigger threat to ethnic and national languages. It is the power of globalization that is a sweeping cultural and language domination. How will Eritrean languages fare in such global phenomena? The primacy of Arabic, Amharic or Tigrinya will be irrelevant facing a much bigger threat of Westernization through globalization, when English becomes lingua-franca for the rest of the world, including China.

Awate Forum