Book Review: The Nurnebi File –Espionage and Politics

YeNurnebi Mahder: Silela ena poletica (The Nurnebi File –Espionage and Politics), published by Gebriel and son Publishing Virginia, USA, 2017. Amharic text: by Tesfaye Gebreab. 400 pages plus list of references and index.

This a very fascinating book for its imaginative qualities and for putting together some known facts in an imagined world. This is a historical novel, quite well known in European literature but probably the first of its kind in Ethiopian (Amharic) literature. This book is a story of Nurnebi and the fate of his descendants up to the fourth generation. It is also a story that covers the history of Eritrea, through the lives and times of the Nurnebi and his sons from its creation as a colony in 1882 until 2015.

In the summer of 2015, Debesai Gebriel, the fourth descendant of Nurnebi gave to the author, Tesfaye Gebreab, hence TG, a number of documents that were kept hidden by Debesai´s mother for many years. There is no doubt that some documents were handed to the author. But to claim that the book is a true account of the lives and times of the four generations (from Nurnebi to Debesai Gebriel) based on such documentation is to underestimate the critical faculties of his readers. To a great extent the book deals with TG´s grasp of the history of Eritrea where the four descendants of Nurnebi lived and died. I believe this critical remark would become more clearer as I proceed with the review of the book.

The reader has to plough through half the book to find out the nature of the documents that Debesai Gebriel handed to TG. It is a single criminal/pollical file compiled at Mogadishu containing a case against Gebriel Edmundo Gebre Medhin and thirteen other Eritreans for being spies of Ethiopia or working for Ethiopia (pp. 197-98). This is the file that TG imaginatively used as a title and organizing principle for his book. The file does not mention the name of Nurnebi for two reasons. The first reason is that the name Nurnebi was changed into Gebre Medhin. The second was that the memory of Nurnebi was not recorded in the colonial archive.

I am fairly acquainted with the Italian colonial archives and I wrote an article on Resistance and Collaboration in Eritrea, 1890-1914 (published 1982) I did not come across a file on Nurnebi Bechit, because he was not captured and because he was not considered as serious as people like Mohamed Nur.

The Italian colonial archives contain thousands of files covering all aspects of the law. There is a file for every person charged with a political or other crime and brought before a court of justice. Access to these and other archival material is restricted but I am almost certain that the file of Gebriel Edmundo Nurnebi was accessed from the Central Archive at Rome (Archvio Centrale dello Stato) where the archive of Rodolfo Graziani (first governor of Somalia and later governor of Ethiopia up to 1938) is deposited.

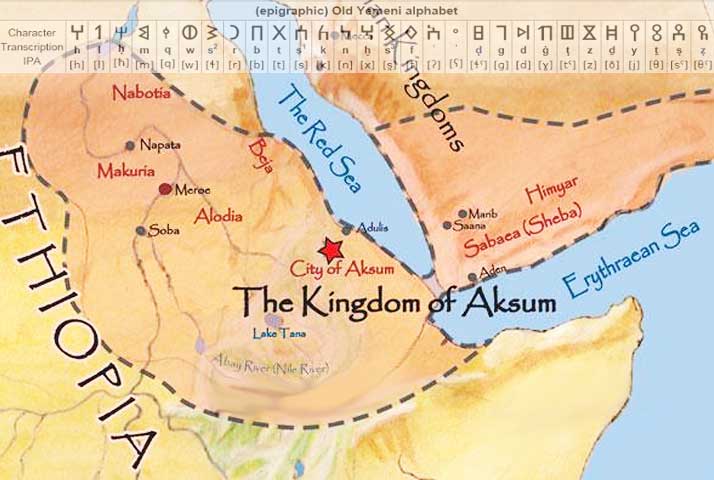

Nurnebi Bechit from Halhal (Bogos, Bilen) left his village in 1888 during the first year of the great famine, (1888-1892) with his two sons; Idirs and Adum. Nurnebi was from Bet Tawke, one of the two major clans among the Bilen..

Nurnebi saw initially the benefits of Italian colonialism; they abolished slavery; abolished the threat from the highlands over the lowlands and provided food to the hungry and were much better than the Egyptians and the Turks before them.

TG describes Italian colonialism as no different from Ethiopian colonialism; the only difference is that the Italian are white and they came from beyond the Sea; all are invaders. As to the Ethiopians, they were not united since they had no common bonds that united them (p.39). Where did TG get the empirical material (from the files that Debesai Gebriel handed) and how was that material composed. Was it Nurnebi himself who described Italian colonialism as not different from that of Ethiopian colonialism? If so, how was that tradition transmitted?

The description of Italian colonialism cannot be attributed to Nurnebi and his descendants. It is the opinion of TG but put forward as if it was the expressed opinion of the Nurnebi. I shall cite another example. Between 1890 and 1891, the Italian colonial state eliminated more than half of the traditional political elite together with their supporters. Over one thousand people were summarily executed in a pacification process, described by contemporary writers as the genocide of the inhabitants of Massawa. TG mentions the massacre of Massawa but dismisses it by writing that at that particular moment Menelik was engaged in the process of handing over hundreds of thousands of Oromo to slavery (123). The issue is not whether Italian colonial genocide is comparable with the slave trade policies of the Ethiopian state of the period. The issue is whether such a comparison can be made on the basis of so called Nurnebi file that TG was handed by Debesai in 2015.

TG can entertain any political or historical view of Eritrea and its past. My aim as a reviewer is not to interrogate the accuracy of his historical reading but to point out his false claim of writing the truth as if the truth was available in the Nurnebi file he got from Debesai.

Let us continue to narrate the life of Nurnebi, his two sons (Idris and Adum) and Meryem, Nurnebi´s sister. Nurnebi and his two sons (Idris and Adum) arrive in Massawa around 188. After some time Nurnebi got a job and his two sons were with him; they all stayed at Meryem´s home, Nurnebi´s young sister.

When things appear settled (the overcoming of hunger and the securing of job), Nurnebi, rebelled against the Italian rule and decided to carry out armed resistance. The pretext is rather insignificant; he was insulted by a drunken Italian. Nurnebi shared the information with his other co-workers who told him that they have been subject to far more insult (the amount of insult) than him and advised him to live with it and take care of his family. Nurnebi, however, was so proud and his humiliation so profound that he sacrificed his sons and sister and joined the anti-colonial resistance movement (p.52). This happened sometime in 1891.

Nurnebi remained fugitive (from the perspective of Italian colonial laws) and fought on the side of Bahta Hagos, (p.134) the leader of the first significant rebellion against Italian colonial presence in -Eritrea in December 1894. Nurnebi continued to fight against the Italian armed forces from Ethiopia and he participated at the famous battle of Adwa (pp.135-143) as part of the armed unit led by Gebremedhin, the son of Bahta Hagos. Nurnebi survived the battle of Adwa and had wished that the forces of emperor Menelik had crossed the Mereb river and drove out the Italians from the Eritrean landscape (p.152). But the people of Shewa (the soldiers of Menelik), after securing their border with Italy, decided to go back to their villages. Despondent but resolute, Nurnebi chose the mountains of Halahal to hide from the clutches of Italian colonialism, than to either submit to the Italian authorities or join the forces of Menelik, , like many of his colleagues did. The final days of Nurnebi remain obscure and shrouded in mystery. Some say he joined the remnants of the rebel group led by Gebremedhin the son of Bahta Hagos. Others rumoured that he joined Mohamed Nuri another well-known Saho anti-colonial rebel. TG wrote that Nurnebi remained alive in the memory of the people of Halhal until 1900. He was forgotten from the annals of Eritrean history until 1935 when his name and memory surfaced again in connection with the Italian invasion of Ethiopia (p.160).

TG´s biography of Nurnebi is deficient in some important aspects. Nurnebi is not put into the context of the history of the region. TG hardly discusses the implications of Nurnebi´s close collaboration with other anti-colonial rebels in the region and especially the common cause he created with Bahta Hagos. In the hands of TG, Nurnebi appears to be highly erratic pushed by irrational impulses and with a personality disorder that preoccupied his co-workers. A much better biography of Nurnebi could have been written even by TG himself.

I believe the problem of treating Nurnebi in such unsatisfactory manner is around TG´s perception of Italian colonialism. If Italian colonialism, is not different from Ethiopian or Tigrean colonialism (which is the position of TG) then it becomes very difficult to do justice to people like Nurnebi, who devote all their lives to fight against the presence of foreign rule. TG cannot really figure out what drove Nurnebi.

Meryem, unable to bring up the two sons of her brother Nurnebi, decided to hand them to the Catholic Mission at EMikullo (11 kilometres north of Massawa). The sons of Nurnebi were very well received; they were converted to Catholicism. Idris became Eduardo and Adum became Edmundo. Their father´s name Nurnebi was changed to Gebre Medhin (p.113). Eversince then, they were known to the Italian bureaucracy as the sons of Gebre Medhin.

Idris/Eduardo became a colonial soldier in about 1895 (p.130), whereas, Adum/Edmundo became a clerk in the colonial administration. There is no record that the sons of Nurnebi fought for Italy at the battle of Adwa. It is most probable that Idris/Edward was still too young.

One of the Eritreans who fought at the battle of Adwa as an Italian colonial soldier (known as ascari) was Yacob Tewelde who was more or less the son of Meryem the sister of Nurnebi. It was estimated that up to 2000 Eritrean colonial soldiers were killed together with 4 600 Italian soldiers at Adwa on that fateful day of March 1, 1896. About 800 Eritrean soldiers were captured as prisoners and Yacob Tewelde was one of them. The Eritrean soldiers were accused of treason-(for fighting against their king and country) and thus were subjected to due punishment, which was the amputation of the right arm and the left leg (147).

The sons of Nurnebi begun their adult lives in the beginning of 1910s. Eduardo went to Libya as a colonial soldier in 1912 ( one of the first to be recruited) and his brother Edmundo found a job at the post office and ended up with the covetous title of Cavaliere (p.169). Eduardo returned from Libya in 1920. Yacob Tewelde survived the amputation of his arm and leg and returned to Eritrea and lived the rest of his life partly on his own skill as a farmer and partly as pensioner of the Italian colonial army.

TG described the political and cultural environment of Eritrea after the battle of Adwa. TG wrote that Menelik sold Eritrea to Italy not only once but twice (p.159). In the words of TG, Nurnebi said “Menelik has defended his borders and he will be remembered by history. Now the burden of solving the problem [the presence of Italian colonialism in Eritrea] rests on us” (p.154).

One of the lessons that Italy learnt from the Bahta Hagos uprising of 1894was the negative impact of expropriation of land. Italy shelved aside its policy of land expropriation and evolved a new policy of persuading the Eritrean to abandon his land for employment in the modern sector and the colonial army. TG wrote (p. 158) although the policy did not move as fast as expected, in few years Eritrea became the country of industrial workers (Yefabrika serategnoch ager honech).

I agree that the period from 1896 until 1932 is described as the best period of Eritrean colonial history. Peace with Ethiopia was established and maintained for nearly 40 years after Adwa. The economy was highly subsidized from Italy. Eritrea did not become a country of factory workers – far from it; it became the producer of the legendary soldiers (known as ascaris) at the service of Italian expansion elsewhere. It was only after 1935 and especially during the first phase of the British Military Administration, 1941-1945, that Eritrea became comparatively speaking the country of industrial workers.TG fails to mention that about 40 per cent of the able bodied Eritrean men were recruited into the colonial army as cannon fodder first in the invasion of Ethiopia and later until 1941 in its pacification. The Eritrean rural economy was left to ruins as a consequence.

Life was good for the sons of Nurnebi and their very close relative Yacob, Tewelde. Eduardo had, as a soldier a rougher time but his younger brother Edmundo was very much privileged as a high clerk in the colonial bureaucracy. Moreover, he had several opportunities to visit Italy. Their schooling at the Catholic Mission in Massawa had given them a competitive advantage and their loyalty to the Italian colonial system reinforced their position of privilege.

There is no record as to the private lives of the sons of Nurnebi but TG wrote both sons of Nurnebi were married and had children. Gebriel and Michael were the sons of Edmundo Nurnebi. Estifanos was the son of Eduardo Nurnebi . Tewelde had a son named Iyassu. The grandsons of Nurnebi were educated at the Catholic School in Keren and were converted to Catholicism, whereas Iyassu, the son of Yacob was educated at Evangelical School at Beleza (p.179).

But in the 1930s the sons of Nurnebi (Eduardo and Edmundo) begun to criticise the policies of Italian colonialism and the role assigned to the Eritreans. By 1935, the sons of Nurnebi had developed a very critical attitude towards Italian colonialism.

On the eve of Italian invasion, Eduardo and Edmundo and their children and their families were transferred to Somalia; their loyalty to Italy was suspected (p.190).

TG leaves the sons of Nurnebi exiled in Somalia. They do not display sophisticated awareness other than vague criticism against Italian colonialism and its ambitions to invade Ethiopia.

Gebriel, the son of Edmundo and the grandson of Nurnebi was, thanks to his education at the Catholic School in Cheren, employed as a clerk in the government in Mogadishu, while his childhood friend Iyassu Yacob Tewelde was placed at the Italian intelligence unit after a short training in Italy (p.179). His cousin Estifanos Eduardo Nurnebi born around 1910, was also exiled in Somalia.

Although the Italian invasion of Ethiopia took place on October 1935, preparations for war started already in 1932. One of the few Eritreans who followed the developments keenly was Gebriel, the son of Edmundo Nurnebi. Gebriel rejected the widely spread belief that Menelik sold Eritrea to Italy. Gebriel argued that Menelik did not have the power to sell Eritrea to Italy; he signed the peace treaty because he did not consider Medri Bahri (Eritrea) as his own territory. Menelik, would not negotiate over Aksum because he believes that Aksum is the origin of [the nation] (p192).

Yet, few months before the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, Gebriel, his cousin Estifanos and his uncle Eduardo, together with 12 other Eritreans were brought to a military court in Mogadishu on charges of treason – for spying for Ethiopia. And on 30 October 1935, Gebriel was sentenced to death. The case against Gebriel appeared convincing; he was accused of writing such statements: “It is a sin to participate in the war that Italy is planning against our Ethiopian brothers “(208). Estifanos Eduardo was condemned for 16 years imprisonment.

Due to his high education and the reputation of his father (Cavaliere Ednumdo), Gebriel was a privileged prisoner. He was interrogated by the political office from Asmara with the intention of changing the death sentence into life imprisonment. But Gebriel was intransigent; he defended his support for Ethiopia. TG makes Gebriel state categorically that “Eritreans would prefer their underdeveloped lifestyles than to live in material comfort under racist colonial rule. People long after the life that they had before your arrival” (pp. 225-6).

The death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment due to the intervention of his friend Iyassu Yacob Tewelde, who had a high position at the colonial bureaucracy. Eduardo Gebre Medhin alias Nurnebi was soon released as he was not in any way implicated. His son Estifanos was also released.

Iyassu the son of Yacob Tewelde entered Addis Ababa with the victorious Italian army. Iyassu Yacob supported the Italians in Ethiopia throughout.

On December 1939 Gebriel, while still in prison, got his second child Debesai (the first died soon after birth) the fourth generation of the Nurnebi line of descent.

When Italy invaded Ethiopia, TG wrote that many Eritreans from all corners demonstrated to which side they belonged; they were on the side of Ethiopia. TG further wrote that those Eritreans who suffered a generation under racist system came out in support of Ethiopia. And those Eritreans who had sought refuge in Ethiopia prior to the war joined their Ethiopian patriots against Italy. Moreover, Eritreans who had better education (and they were considerable) were at the service of the Ethiopian imperial government such as Lorenzo Taezaz and Efrem Tewelde Medhin (238-239). Furthermore, TG presents in concise form the hundreds of Eritreans who defected from the Italian army and joined the Ethiopian resistance forces which made Italian occupation extremely tenuous.

Was it really the racist colonial policies and praxis alone that pushed Eduardo, the son of Nurnebi and Gebriel, the son of Edmundo Nurnebi to support Ethiopia and its struggle for liberation from Italian occupation? TG mentioned Lorenzo Taezaz and Efrem Tewelde Medhin, Eritreans who worked for the emperor in exile and after. Were these people contributing their services as an act of solidarity of black people supporting other black people in their war for liberation against white rule?

As far as Ethiopia is concerned, all the Eritreans who fought on the side of their Ethiopians compatriots did so as Ethiopians and those who survived the war were treated and rewarded as other Ethiopians. TG cannot share this view because he had already made up his mind that Eritreans joined Ethiopians in their war against Italian occupation as black people helping other black people. TG knows very little about the working of Italian colonialism in Eritrea and how it interacted with the various ethnic groups in the country. Many Eritreans in the highlands (as opposed to those in the lowlands), continued to resist the presence of Italian rule as Ethiopians. In 1986 I published an anthology of my articles on Eritrean reactions to colonial rule under the title: No medicine for the bite of a white snake: notes on nationalism and resistance in Eritrea, 1880-1940. TG did not either discover it or deliberately ignored it.

Eduardo Nurnebi died and was buried in Mogadishu while his brother Edmundo was buried in Asmara. TG does not provide information as to when the brothers died but it appears that they died before 1940. (p.272) Yacob, their friend was alive as well as his son Iyassu, all staunch supporters of Italian colonialism. In the early months of 1940, the grandson of Yacob Tewelde (whose name is not mentioned) was recruited by the Italians to fight against the British.

Gebriel Edmundo Nurnebi was released in 1941 and he soon became a friend of the most influential people in Ethiopia. Gabriel served as high government official from the early 1940´s until his death in 1983. And he supported the union of Eritrea and Ethiopia. Gebriel Edmundo was a very good friend of Ras Asrate Kassa, the governor general of Eritrea and a member of the Ethiopian Imperial Crown Council (p.339).

TG devotes many pages on the political events that took place in Eritrea – a description that shows very little knowledge of the political dynamics of the region.

Gabriel Edmundo Nrunebi and Iyassu Yacob Tewelde met in Addis in the late 1960s. Iyassu lived in Rome, but a had son, Fedai (born 1953) who later joined the Eritrean Peoples Liberation Front (established 1971).

Debesai and Mekonen, the great grandsons of Nurnebi grew in Addis Ababa. Gebriel and Lula his wife had ten children. Mekonen was a friend of Mohamed Kidan (bron 1948) in Cheren and an active member of the Eritrean Liberation Front (established 1961). In 1976, Mekonen the son of Gebriel, the son of Edmundo and the son of Nurnebi joined the EPLF (P.344). The circumstances for joining the EPLF show the immaturity of youth and a communication gap between children and parents. He was persuaded to join the Eritrean Peoples Liberation Front on the rumour that Eritreans were not allowed to compete for positions at the Ethiopian Airlines because there were already too many of them. Mekonen joined the EPLF in 1976 and died in the battle front in 1982.

Gebriel and his wife moved to Asmara in the 1970s and Gebriel died in August 1983 (369).

Habteab Gebriel who lived in the USA came to Eritrea via Sudan at the height of the “Eritrean war of Liberation” looking for his brother Mekonen (374). He found out, much later that is after the independence of Eritrea, that his brother died already in 1982.

Iyassu Yacob Tewelde returned to Asmara from Rome and died towards the end of 1994.

Fedai Iyassu (born 1953) and Debesai Gabriel(born 1939) were alive in Asmara in 2017 when the book went to print.

Now that I have described the contents of the book, I wish to evaluate it on its merits as a political biography of the Nurnebi family stretching over four generations. This is not a political biography of Nurnebi and his descendants. It is a work of fiction woven around their lives. The work does not become more credible because it is built around real people. TG knows very well that he is engaged in a work of fiction, but he allows his publisher to state categorically that it is a true history of politics and espionage. It is a false claim.

TG can invent any history he wishes as long as he informs the reader that he is engaged in work of fiction or invention. He does not have a license as a writer, and much less as a person, to present a work of fiction for what it is not.

There is no file on Nurnebi Bechit in the colonial archives. But there is a file on Gebriel Edmundo Gebremedhin. We know Gebre Medhin was the Christian name imposed on Nurnebi by the Catholic mission at the time when his two sons were admitted.

TG can create a Nurnebi file which he did. TG has all the right to exploit his creative imagination. But he crosses an ethical line when he fails to inform his reader that the Nurnebi file is a work of his imagination.

But how good is it as a work of fiction? It is bad because TG fails to draw the line between what he writes and what his characters believe and write. His treatment of Nurnebi is beyond all criticism. He deserves a much better treatment – similar if not more than that given to another contemporary of Nurnebi, namely, Blatta Gebre Egziabeher Gilamariam.

The Nurnebi brothers (Eduardo and Edmund) are not given much voice and the social and political environment they lived is not well presented. Italian colonialism was experienced in more complex ways than TG could grasp. I think TG could have done some more research and describe even in pictures the evolution of Asmara and other towns and the strategies that Italy used to keep and control Eritrean resistance. Edmundo was a staunch supporter of Italian colonialism, whereas Eduardo was not. TG could have elaborated much more on how and why the two brothers (well paid by the colonial system) had different understanding of Italian colonialism.

Even the life and times of Gebriel Edmundo Nurnebi is treated in a very shallow manner, apart from the fictious conversation between Gebriel and the interrogating political officer from Asmara. Gebriel spent most of his life in Ethiopia, as high government official and he supported the union between Eritrea and Ethiopia, in the 1940s and 1950s. Why did Gebriel perceive the union of Eritrea with Ethiopia as a form of liberation of Eritrea? TG provided no information on the political thinking of Gebriel. TG did not want to describe the world of Gebriel as Gebriel would have wished it because TG did not support the politics of Gebriel.

The centre point for the book is the young boy Mekonen Gebriel who joined the Eritrean Peoples Liberation Front in 1976 and who unfortunately died in battle in 1982. The memory of Mekonen was cherished and kept alive by Debesai, his elder brother. The documents were handed in a free and independent Eritrea in 2015. In reality, TG was handed a single file and some family mementos.

The Nurnebi file shows the ambiguity of TG as regards the history of Eritrea and Ethiopia. On the one hand TG maintained that there were no bonds (cultural, political ideological) that united the people of Eritrea and Ethiopia. On the other hand, he is forced (by the positions the sons and grandsons of Nurnebi took on Ethiopia) to deal with their history and reluctantly agree with them. Yet he does a rather poor job of it all. However, in spite of its shortcomings The Nurnebi File tells more about the bonds that unite the peoples of Eritrea and Ethiopia – resilient bonds that withstood colonialism and other external interventions – than TG is willing to admit.

Awate Forum