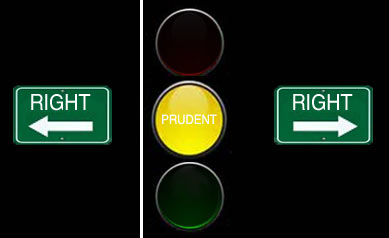

Being Right vs Being Prudent

To plough on, oblivious to risks, is the stuff of legends. The rational mind assesses risks and judges some to be too high. Even a compulsive gambler will look at the cards he’s been dealt and at the stakes and then withdraw: too rich for my blood, is the common expression. Too high of a risk. In Tigrigna, the equivalent expression for too high a risk used to be ayewatSa’anan iyu. We may be able to get in, but we won’t be able to get out. It is a trap. Now, in our military culture, to express doubt, or to conduct proper risk assessment is called tesa’Arnet: defeatism. Faced with any risk, one must always choose the riskiest. To choose the less risky, to express doubt about a path full of precipice, is to beg for the label of a defeatist.

Call me an elitist, but I think at the next AU meeting they should mandate that every African head of state should take a course in cost accounting and risk assessment. Then they should take a test; and those who flunk it should be removed from power. There can be exemptions for democratic states. Because it is only in non-democratic states (read: Africa), that the people, and not the leaders, who pay for the miscalculations.

Being Right vs Being Prudent

Faced with a frivolous lawsuit from an ex-employee, a CEO of a publicly-held company has options. The CEO, who has a fiduciary responsibility to the shareholders to maximze profit, knows there is no case, the charges are trumped up and he can prove this in a court of law. It will cost $500,000 to prove that he is right. But it will cost $50,000 to settle the case. Does he go to court or does he settle? Does he prove that he is right does he do the prudent thing?

Consider the Host of the AU: a man who, while the world was begging him not to, orchestrated a wasteful War of Choice by describing it as a Necessary War, is now lamenting the wasteful decisions of African governors.

Ah, it is the “principle” of the thing. It is the “bottom line.” “Principle” has become the refuge of the stubborn, the halo of the self-righteous. Remember 1999. We cannot accept this treaty because, among other things, it allows Eritrea 45 days after it signs an agreement to withdraw from the contested territory. So argued Ethiopia in reference to the Technical Agreement. Then it spent 9 months—270 days— and declared a war of devastation to make the point that 45 days was too long.

For the sake of “principle,” Ethiopia made that wrong decision in 1998. For the sake of “principle,” (final and binding) Eritrea is making that wrong decision now. Two years and counting. You know what I am going to say; but I know what you are going to say. But first, another example.

THE RISKS OF…

Remember the scene from the movie Young Frankenstein? (Correction: “It is Franken-steen!”) If you don’t, you should check it out; it is a Mel Brooks adaptation of the horror movie. The doctor is about to go to experiment on the monster he has created and he tells his assistant that once inside the laboratory, he will probably scream and cry for help but that she (the assistant) is to absolutely disregard his cries for help. He reminds her of this instruction several times. A few seconds later, the doctor cries for help. What does the assistant say? Exactly: the equivalent of “no, our deal was final and binding.” The frantic doctor cries for help, “open the damn door, can’t you people take a joke. I was joking!”

“…DIALOGUE”

Those who are opposed to dialogue (“let the doctor be swallowed by the monster he created!”) not just on the basis of principle but also on the argument that this is a risky venture make the following argument. Once you agree to enter into dialogue, you are forfeiting whatever advantages you had with the ruling of the Boundary Commission and you are agreeing to start from Zero. And given the Ethiopian Government’s unreliability when it comes to upholding agreements it has signed, you are exposing Eritrea—including future generations—to an unacceptable level of risk. If you agree to an open-ended dialogue, then there is no guarantee that the dialogue won’t drag out for generations and that new elements won’t be introduced to the agenda that will make reaching an agreement less and less likely.

Those of us who have argued for immediate dialogue have done so on the basis that, yes, there is a risk, but that risk is considerably mitigated if you have a vested interest from all parties to find a solution and that this vesting is likely to dilute over time until there comes a time when no one will be interested. (We compared it with Palestinians useless “Resolution 242.”) The dialogue is not likely to be “open ended” and the scope of the agenda of the discussion is likely to be limited given that (a) the party representing Ethiopia now (TPLF) has accepted the sovereignty of Eritrea (no small thing given the other alternatives) and (b) it has also officially accepted the partial demarcation of the non-controversial parts and (c) it is, like all governments, concerned about its international reputation.

Given all of the above, the dialogue proponents are saying that a mutually agreeable arrangement can be made provided Eritrea and Ethiopia adopt a less adversarial relationship and negotiate in good faith while the focus of the international community is still concentrated on the Eritrea-Ethiopia dispute.

“… FINAL & BINDING”

Now, let’s consider the risks of insisting on “Final & Binding,” not on the basis of the abstract (which is a slam dunk), but based on reality. Internally, the political dynamics in Ethiopia discourages the Ethiopian government from making any concessions and this attitude is hardening and is unlikely to be reversed. Externally, there is no evidence that the international community has the stomach to apply any pressure on Ethiopia. (The international community doesn’t even have the stomach to intervene in Darfur.) As recently as this week, Koffi Anan, in his meeting with President Isaias Afwerki, was reported to have spoken admiringly of how the Cameroon-Nigeria border dispute was resolved (face-to-face dialogue.) Thus:

- The adamant refusal by Ethiopia to accept and implement the ruling of the boundary commission is very unlikely to change;

- The international community is very unlikely to take substantial measures that will compel Ethiopia to reverse its decision;

If one agrees with the assumptions above, what we are really saying is that we have to wait until the government in Ethiopia changes for us to get our “final and binding.” Right? Now, two more assumptions:

- The Ethiopian government is very unlikely to lose power in the next election and;

- Even if it does, the Ethiopian opposition that has opted to participate in the Ethiopian election is even more strident on the issue of Eritrea and even less likely to fully implement the Algiers Agreement,

Now, if we add all the assumptions, what we are really saying is that the “final and binding” boundary decision will be implemented only when there is a violent uprising in Ethiopia that results in (a) a government totally committed to implementing the Algiers agreement and one where (b) the deposed Ethiopian powers will submit to the new powers.

FURY, FALSE HOPE, PRIDE

Of the two approaches—dialogue vs insisting on “final and binding” not just in the abstract but the real–which approach is riskier? I maintain, and I believe most rational people do, that the insistence on the “final and binding” in the face of these realities is imminently more risky.

The government of Eritrea knows this. And its job is to make us less rational. It does this by giving us doses of fury, false hope and pride.

It is not hard to be furious with Ethiopia and the international community because it is justified. Even the Eritrean opposition, which, given its fixation with “principle” has never met a lost cause it didn’t like, has allowed itself to become a pale imitation of the “final and binding” chorus line. But sustaining this fury is a full-time job, which is why the government media is always reminding us of the terrible deeds of the Ethiopian government (going back to the 1940s if necessary) and the international community.

When the government of Eritrea is not stroking our rage and fury, it sells us false hope that will make it more likely for us to consider the implausible. It tells us that its shuttle diplomacy is swaying the international community. Simultaneously, it paints a picture of Ethiopia as one that is on the verge of collapse, a state whose soldiers are defecting en masse and its armed opposition scoring tide-changing military victories.

Even those who don’t buy any of these emotional manipulations hold out because they just cannot allow Eritrea to lose face. Pride precludes negotiation because this would mean that Ethiopia won. But this pride is misplaced because the irony of this “principled” position is that there is nothing in the Algiers Agreement or even the ruling of the Boundary Commission that precludes Eritrea and Ethiopia from entering into a dialog. Even if one is a stickler for the rules, while it is true that the Agreement does not compel either party to enter into negotiations, it does not prevent them from doing so, either. More, it is better to win peace and lose the mechanics of peace than to win on the mechanics of peace and lose the peace.

THE COST OF “STAYING THE COURSE”

Which takes us to the cost item. Of course Ethiopia is wrong. Of course Ethiopia should have not reneged on a rock-solid agreement. Of course Ethiopia’s actions set a bad precedent for other international agreements. But the reality is that it is Eritrea and Eritrea only that is paying the brunt of the post-war environment: the peacekeepers are in Eritrean territory; it is Eritrea that suffers from a state of no war no peace. Ethiopia, for geo-strategic reasons, is far from being punished, actually being pampered and is likely to be, as long as the Meles Zenawi regime is in power.

Eritrea has now been denied peace and security for six years. And, its current government is telling it that its peace and security will come about when there is total war in its neighboring nation, Ethiopia.

Meanwhile, the Eritrean people should wait. A year, a decade, a century, it doesn’t matter: because it is not the government that is paying, it is not the opposition, but the ordinary people. And we always have time. This time will give us more time to commemorate events and count our enemies; we will build new monuments to newer gods. Worse, given that Eritrea has not ruled out war (in his Independence Day Speech, President Isaias Afwerki said “patience has its limits” and we all know what that means), and Ethiopia, despite is lip-service has not (if war starts this time, we won’t know where it will end) we may even force new members to an esteemed and venerated club that does not want to receive new members: our martyr’s club.

The world is unfair; our anger is justified; the Ethiopian government is slippery. All true. But what the people of Eritrea want is not an explanation why they don’t have peace; and they are not looking for slogans and expressions of solidarity. What they want is a solution. What they want is peace. And those who claim to lead us should remember that the first and second orders of any government (including the opposition, if they ever come to power) are to provide peace and security for its citizens.

NB: This edition of AlNahda is from the archives. It was first published on July 8, 2004.

Awate Forum