Education not Incarceration: Build Schools not Prisons

Education is central to Eritrean culture. During the 30 year revolutionary struggle Eritrean nationalists made a conscious effort to formally educate the villages they sought refuge in. Amongst a chaotic backdrop of air raids and gunfire, mobile workshops and literacy programs were run to empower local women, children and potential fighters (Rena, 2007; Pool, 1997). In the hearts and minds of nationalists, a literate population was seen as most prepared to fight for their freedom through the reading, writing and public sharing of revolutionary literature. As a hallmark of the revolution, the PFDJ committed itself to universal education upon ascendance to power in 1991. All members of society were promised the provision of political, cultural and economic education regardless of tribe, region, class or gender. However, nineteen years after independence it is all too obvious that the PFDJ’s has aborted its commitment to education. With the moving of the final year of all high schools to Sawa (military training grounds) in 2003, the closure of the University of Asmara in 2006, and the Nazi’esque crackdown on academic freedom, the right to education has never been so absent from Eritrean life.

The greatest threat to future generations may be the PFDJ’s current priority to build more prisons than schools. Underground prisons are bursting at the seams and new ones are under construction. We should interpret the desperate race to build prisons to mean two things. First, the PFDJ is indeed facing resistance from Eritreans at home. (This is best evidenced by the recent assassination attempt against Isaias last August). Second, it views the country’s population as more fit for incarceration than education.

In an ironic reproduction of colonial violence, the regime has even resurrected the use of Alla and Nakhura Island as torture centers. The two locations were previously built and operated by Italian forces to torture Eritreans who opposed occupation (Human Rights Watch, 2009). In an even more ironic reproduction of colonial violence, PFDJ torturers have appropriated some of the techniques used against Eritreans by the Derg. For example, water boarding or “mock drowning” as prison guards popularly refer to it is used against many prisoners of conscience (Human Rights Watch – “Service for Life”, 2009).

Casual education outside of the classroom is also under attack. In recent years the PFDJ has banned groups of seven or more from gathering publicly, thus, preventing any collective conversations from taking place on the now-destitute streets of Asmara (Connell, 2004). Oral histories and Indigenous traditions of learning have also been abandoned in favor of Western ones. Therefore, any understanding of “education rights” must include a respect for the transmission and practice of Indigenous knowledge.

Of particular urgency is the growing number of women facing sexual violence in schools, military training grounds, and other public spaces. International observers have found that “those who are recruited (to the military) are more at risk of rights violations, rape, and sexual harassment in particular” (Human Rights Watch – “Service for Life”, 2009). However, whenever human rights organizations raise the issue of rape, Isaias’ and his cronies go deaf to the warnings, and only continue their policy of silence and complicity in regards to the issue. The fact of the matter is the daughters of the nation are most at-risk under the patriarchal watch of PFDJ politicians and foot-soldiers, who in many cases are the most likely culprits of violence against women.

Perhaps most crucial to the fostering of a healthy learning environment is the maintenance of inter/intra-national peace; a peace in which aggressive military build up is no longer necessary. How else are our youth expected to learn? Especially when they read, write and perform in schools knowing that all roads to graduation lead to unavoidable military conscription. For those already in their last year of high school diplomas are almost immediately replaced by rifles. Leading one former teacher at a Sawa school to recall that “students could not study. They [are] always being forced to leave the class for some kind of military service” (Human Rights Watch – “Service for Life”, 2009). Such disruptions to the learning process are no doubt caused by the omnipresent position of the military industrial complex in Eritrea, and its ability to dwarf other social concerns such as education.

When Human Rights Watch put together its 2009 report entitled “Service for Life”, the international watchdog warned against the “multi-faceted repression” created by indefinite military service. In the 1995 Proclamation outlining its military program, the PFDJ summarized that to serve in the military was an utmost nationalistic duty that worked “to foster national unity among our people by eliminating sub-national feelings” (Eritrean Gazette, 1995). Fifteen years after the proclamation it seems that by “eliminating sub-national feelings” the regime actually sought to eliminate political rivals and competing claims to power. Although Article 8 of the Proclamation ensured that military service would span no longer than 18 months, many youth-turned-veteran fighters have been active for the past seventeen years. By 2007 all government pretensions to demobilization ceased, as government members openly stated fighters would serve in the military as long as they saw fit. And yet outside of the short-lived Border War with Ethiopia and Isaias’ failed attempts to bait Sudan and Djibouti into war, there has been unequivocally no need for an agro-active military. Unless, of course, that agro-active military was being used as proof of a looming threat of invasion, and the looming threat of invasion was itself a ploy to distract the masses from political-economic mismanagement on part of Isaias’ regime.

By way of conclusion, it may be worth ending with a message to the blind nationalists who live life with the wool (or should I say flag) pulled over their eyes. Whether in the Diaspora or in the country proper, the blood of resistance stains your hands as it does the prison executioner’s. When Isaias is dragged through the streets to answer for his crimes, you too will be held accountable for those brave young men and women who rot away in underground prisons. In the nation-(re)building moment of tomorrow, you will be judged by the moral compromises you make today. For when the prisons are opened and the bones of the dead are collected, and when grieving mothers flood the streets to remember the loved ones they have lost, the tragedy of history will not be that you watched it all happen, but that you did nothing to stop it.

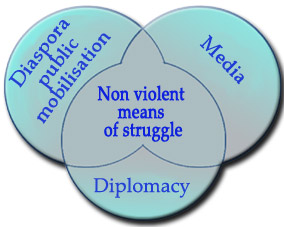

In our current campaign to advocate for “Education Not Incarceration”, Eriforum recognizes that above all, the right to education includes the right to:

1) Access, produce and share knowledge free from persecution (including sexual violence against women, indefinite military conscription, unlawful imprisonment, torture or spiritual injury)

2) Speak and organize freely under constitutional protection

3) Take part in participatory political processes that allow all Eritreans a voice in local, regional and national governance

4) Practice Indigenous knowledge (including investment in and curricular use of local languages in addition to Arabic, Tigrinya and English)

We like to hear from you; please commet:

Awate Forum