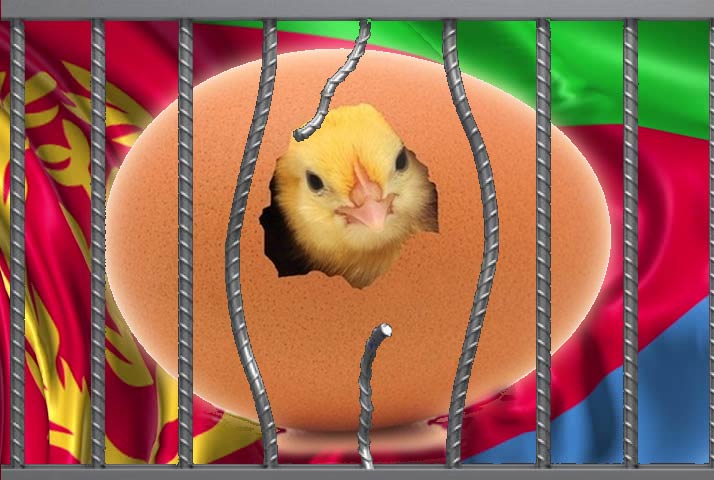

Prison Break: A Microcosm of Popular Uprising Against Tyranny

The inspiration for writing this article was drawn from a piece aptly titled “Seventeen years in Prison without Charge” that recently featured on Awate.com. The story of Haj Mohammed Ali Mahmoud the piece narrates is, sadly enough, also the story of thousands of other Eritrean prisoners that are wasting away in PFDJ jails for no reason other than that a police state decided they be left to rot there. It is atrocious that the arrest and confinement of thousands of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience took place without due process of law. It is even more so

that their fate is entrusted not to the dictates of the law, but to the whims of a ruthless dictator.

Arbitrary incarceration in Eritrea – along with its attendant cruelties of indefinite detention, solitary confinement, torture and disappearance – is an injustice that is linked to a host of other realities of political repression and socioeconomic deprivation. Such linkages notwithstanding, however, this article focuses exclusively on the issue of political captives of the regime. The writer takes the view that, as an instrument of oppression, arbitrary incarceration is an evil that can and must be fought on its own without losing sight of the movement’s overarching mission of bringing democratic change.

Learning From the Past; Innovating for the Future

A glaring weakness of the Eritrean opposition movement and a key factor in its lamentable state has been the absence of effective strategies for organizing its activities and for carrying the struggle forward. Indeed, sorely lacking in the movement have been political acumen, foresight and will that are so essential for prioritizing issues, developing a sense of scale (i.e., capabilities owned versus challenges faced) and getting missions accomplished. With such history of inadequacy behind it, the opposition has little to show for its nearly two decades of existence by way of accomplishments or even progress toward attainment of its goal(s). Its activities over this period have included picking, seemingly at random, a variety of often contentious issues and adopting politically opportunistic, hence discordant positions on them. At times, issues were framed and advocated in ways that promoted dissention rather than harmony within the camp.

Individual factions of the movement have not fared much better either. They too failed to prioritize issues and conduct realistic appraisals of their respective political strengths, support bases and financial resources as benchmark for elevating their future contributions to the struggle. Instead, they remained preoccupied with faulting each other’s agendas, activities and positions on issues. Needless to say, these negative factors and attendant inter- and intra-group feuding have combined to severely impair the movement’s potency and erode the capabilities of its constituent factions.

As hinted above, a political movement can succeed against seemingly insurmountable odds by optimizing its capabilities through adopting a canny strategy of tackling the problem in a piecemeal fashion. Application of a ‘problem disaggregation approach’ (PDA) to political activism provides a way of conceptually breaking down a popular struggle into its constituent elements. In practice, PDA improves chances for success by helping identify self-contained and manageable elements of the overall struggle, prepare effective plans for their sequential implementation and undertake execution thereof in a logical and systematic manner.

This article attempts to draw attention to possible operations that committed opposition group(s) could launch in coordination with clandestine cells in Eritrea to undermine the regime’s ever-expanding prison system, and to counter the pain and cowering apprehension it induces in the population. The proposed mission would advance the struggle on its own merits and by exemplifying initiatives opposition forces can take to chip away at the regime’s grip on power.

A Population Under the Yoke of Tyranny

The PFDJ government’s quarter-century rule of Eritrea has made it amply clear that the ultimate goal of the party and the political ambition of its strongman has always been to remain in power indefinitely. To ensure such an outcome, the party has championed political repression, economic deprivation, cultural degradation and national-psyche manipulation as pillars of a dictatorial system designed to subdue and control the population. The result has been a police state where an oversized state intelligence and security service (ISS) equipped with these instruments of oppression is dead set on eradicating any opposition to its rule by clamping down on dissent and crushing the slightest political activism with utter brutality.

The system’s pursuit of its barbarous agenda has so terrorized the country that the fear-gripped population has no choice but to submit to the regime’s absolute power or to join a mass exodus the scale of which continues to shock the world. The notorious ISS advances its mission by forcing ex-freedom fighters and national service conscripts to do its dirty work. These agents conduct surveillance on the population, round up citizens on mere suspicion of dissent, imprison and torture them and keep them locked up indefinitely. Ironically, these are the same forces that defend the country’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and are themselves the victims of the inhuman policies of the very regime they help keep in power.

A: PFDJ Prisons and Prison Conditions

Information provided over the years by human rights activists/organizations, defecting officials, government insiders, former prison guards, etc. has increased knowledge of prisons and prison conditions in Eritrea. It was thus long known that, by the late 2000s, there existed some 300 detention facilities scattered across the country. As the regime grew increasingly ruthless in subsequent years, its incessant roundup of real and suspected dissidents generated tens of thousands of prisoners thereby pushing the number of facilities to nearly a thousand.

Depending on age and location, the country’s detention facilities vary widely in size, quality and accessibility. Old, colonial-era prisons in cities and towns are properly designed, fairly accessible facilities that accommodate thousands of inmates. Contrasting with these major facilities are small-capacity, makeshift prisons that PFDJ established in urban and rural areas. In towns the latter consist of converted warehouses, villas and other private buildings most of which are off-limits to the public. Those in rural areas, on the other hand, are sited in remote locations and consist of crude masonry cells and shipping containers placed above and/or under ground. These are mostly “secret” facilities designed to be geographically and administratively inaccessible.

Incarceration in PFDJ jails is believed to be unparalleled in its hellishness. Living conditions are simply atrocious with levels of crowding that are hard to imagine. For many, torture and sexual abuse and other forms of mistreatment are daily staples of prison life. Prisoners are never brought before the court, neither do they have any legal recourse. Incarceration is therefore indefinite: for some, it has already dragged on for decades; for others, it ended when they were disappeared or extrajudicially killed by the system.

B: Recent History of Prison Breaks in Eritrea

Notwithstanding the profusion of prisons, burgeoning prison population and horrific detention conditions outlined above, there have been no prison breaks anywhere in the country during the nearly 26 years of PFDJ rule. Here the term “prison break” is used in the strict sense to mean a prisoner escape hatched and coordinated by a group of inmates and/or non-inmates, staged inside prison grounds, and resulting in successful escape of more than just a single prisoner or two.

It is true that there had been incidents of a lone prisoner escaping from a PFDJ prison, presumably with the stealthy help of one or two insiders. Two prominent cases are those of Asmara University Students’ former leader, Semere Kesete (who escaped in August 2002) and former Eritrean air force pilot, Dejen Ande Hishel (in February 2014). But, such incidents have been so few and far between that they are more anomalous occurrences than normal events. As such, and because details of their breakout remained shrouded in mystery, the escapees were accorded celebrity status and even glorified as mythical heroes in some circles.

The country has also witnessed another type of prisoner escape which, though by no means frequent, is not all that rare in its incidence having occurred a few times in the last three to four years. Based on opposition media accounts, escapes in this category seem to share characteristics that set them apart from the “solo-escape” cases outlined earlier. Specifically, they (i) involved groups of between four and two dozen prisoners, (ii) were staged outside prison grounds (while prisoners were in the process of being transferred between facilities, or escorted to and from forced-labor sites) and (iii) entailed an ironic spectacle of prisoners being led in their flight by the very armed guards assigned to escort them. These observations suggest that the escapes were the work of aggrieved guards who made a premeditated move during off-prison escort assignments or spontaneously made decisions on the spot.

Regardless of their nature, however, prison escapes during the PFDJ era have been notable neither in their frequency nor in the number of prisoners they catapulted to freedom. This is in stark contrast to the record numbers of escapes that marked pre-independence years when the liberation organizations (both ELF and EPLF) emptied enemy jails of thousands of political prisoners in repeated prison breaks. Special-operations fighters from liberated areas, clandestine cells in enemy territory, operatives and captured fighters inside prison facilities secretly coordinated their ideas to develop elaborate escape plans. Possibly input into devising the plans, but certainly cooperation in their execution, were secured from prison staff who were themselves members of underground cells or else were co-opted onto the plot. These spectacular missions of setting prisoners free targeted not only small jails in rural areas of the country, but also major facilities in cities like Asmara and Adi Quala most of which were emptied more than once.

What Kept PFDJ Prisons largely Unbreached? Facts versus Fiction

PFDJ’s uniquely abominable conditions of incarceration ordinarily would be expected to give anti-regime elements inside and outside of prison the impetus for organizing prison breaks. That there has been not a single mass escape of prisoners all these years is therefore puzzling to many. Unable or unwilling to offer a rational explanation for this record, some resort to peddling false narratives that are contemptuous of the Eritrean people and demeaning of their proud past. They attribute the absence of prison breaks to cowardice of an inmate population that ostensibly lacks courage and resolve to escape to freedom through an ingenious plot or by muscling in on prison security. Some even extend blame to prison guards and to the rest of the population for their alleged tolerance of the barbarity of the prison system.

Coming from unscrupulous sources, such put-downs ought to enrage or discourage no one. Some of these critics are the same entities that often vilify the population at large for “not rising up against the brutality” of the PFDJ government. They hardly lift a finger in support of the opposition movement, but keep harping on these accusations to cover up their own impotence and duplicitous agenda. Others are, of course, disguised enemies of the Eritrean people and their sole objective is to derail the people’s struggle for freedom by unnerving and disheartening its activist sons and daughters.

In truth, the real reason for the absence of prison breaks is to be found in the regime’s strategy for retaining absolute power indefinitely. The regime has been spreading fear and mistrust in the general public so as to disrupt their unity, stifle their yearning for liberty and justice and degrade their capability to bring about change. As noted earlier, the entity that is at the forefront of this campaign is the intelligence and security service (ISS) – the regime’s largest, best funded and most powerful institution and one which operates largely outside the law.

Insider and defector accounts shared by opposition media outlets reveal how the ISS cunningly manipulates the structure and operation of the military establishment to ensure it remains docile. Independent-minded soldiers are reassigned, reprimanded or arrested; army units are periodically broken, merged, reconstituted into new units or relocated; low- and mid-level army commanders are frequently reshuffled. All these are aimed at disrupting the solidarity, loyalty, camaraderie and esprit de corps troops maintain among themselves and with their immediate commanders.

The same sources have also provided information on the scale and intensity of the surveillance and spying work that the ISS conducts on the population. The service has recruited tens of thousands of citizens from all walks of life to spy on their neighbors, co-workers, customers, etc. in almost every residential neighborhood, private enterprise and public institution including the military establishment. The resulting spy network has seriously undermined public solidarity and weakened trust among colleagues, friends and even family members. It is reported that, at least in urban centers, the ratio of spies to targeted population at any given time can be as high as 1:20; and every year or so, the current legion of spies is retired and replaced by a new batch for obvious reasons.

Those who refuse to acknowledge the time-tested resilience of the Eritrean people cannot be expected to perceive the subtle dynamism of power relations between the dictatorship and its subjugated population. The latter’s revolutionary spirit of courage, defiance, tenacity and self-sacrifice which characterized nearly a century of popular struggle against foreign domination is not a random phenomenon which pops up and vanishes fortuitously. Rather, it is an inherent national trait which, while omnipresent in essence, manifests itself with varying levels of intensity depending on the realities of the times. Presently, this trait remains suppressed by the regime’s suffocating surveillance and spying operations. But it is inevitable that power will soon shift to the people’s side causing an explosion of the pent-up popular indignation to engulf the regime and cause its demise.

The Imperative for Synergy between Domestic and Diaspora Efforts

It is common knowledge that, though undoubtedly few in number and small in size, there are teams of underground activists that have been in operation in Eritrea over the last few years. Despite the regime’s pervasive clamp down, some of these groups run a clandestine campaign of educating and agitating the public for change. They propagate national issues and concerns in the society through targeted telephone calls to influential people and selected members of the public, random calls for one-on-one discussion of specific issues, and mass robocalls that encourage people to take community, rather than individual, action to protest repression. Anti-regime messages are disseminated by publishing clandestine newspapers, putting up posters and stickers and distributing leaflets. Other groups have been periodically undertaking operations involving attacks on (or sabotage of) the regime’s military installations and PFDJ commercial interests.

Despite these encouraging initiatives, however, relations between domestic elements and Diaspora groups have remained meager, weak and sporadic. There is thus a need for stronger partnerships across the opposition movement with greater attention directed towards creating an enabling environment for clandestine teams to intensify their operations against the regime. Diaspora opposition groups must advance the struggle by committing to help establish new clandestine teams or strengthen exist ones. This would entail expanding communications and coordination with internal forces, channeling financial and material resources and providing training on equipment use and the techniques of clandestine operations. On their part, domestic activists should capitalize on Diaspora support to plan and execute a campaign of covert operations targeting the regime’s political, economic and security assets.

It is proposed here that prison breaks – to be staged at multiple locations and aimed at liberating as many prisoners as possible – be placed at the top of the priority list of such a campaign. While by no means a panacea for all of the regime’s cruelties and injustices, successful prison breaks would at least spare some victims prolonged suffering and untimely death in PFDJ prisons. No less significant is the impact they will have on the political psyche of the regime and that of the population as well as on the power relations between the two.

Regardless of the number of direct beneficiaries, repeated incidence of such breaks would destroy the culture of fear and the wall of distrust the regime has incited in the society. This would deal the regime a severe psychological blow that shakes its confidence. Contrariwise, sensing the shattering of the regime’s sense of invincibility and the tilting of the ‘balance of power’ in its favor, the population would be emboldened to up the ante on its demand for change perhaps even to the level of insurrection against the dictatorship.

Finally, it must be emphasized that helping the population organize at any level is a critical element that would not only hasten the downfall of the current regime, but also enhance the country’s chances for peaceful transition to democracy.

Awate Forum