The Village Of Wehni-Ber (Chapter 2)

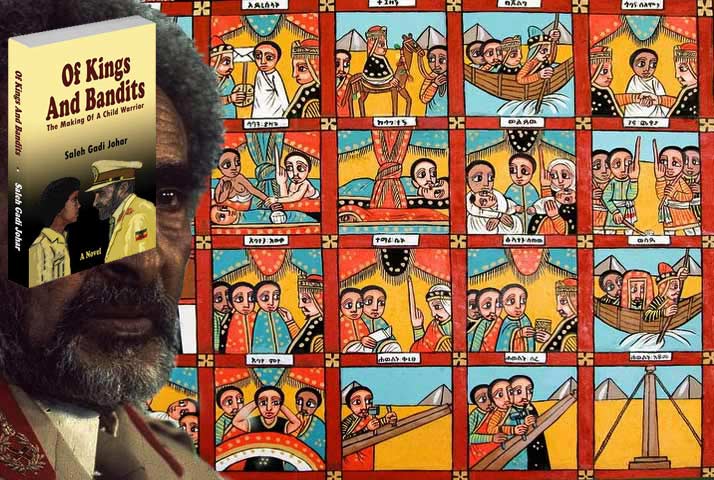

The following is chapter 2 of the historical novel, “Of Kings And Bandits”

________________________________________________________________

Mokria, a young Ethiopian boy, glanced at the Wehni Mountain whose top was covered in thick fog that made it invisible. He felt the cold bite his skin through the blanket he had slept on, which was now wrapped around his body. He waited restlessly by the bush fence outside the family hut until his father finished drinking his morning coffee. The only family cow, all white except for a patch of black that covered half its head and a few black spots on its body, mooed loudly. Left tethered to the eucalyptus tree in the cold, it could have been complaining. Mokria looked at the coop beside the entrance to the fence; the chicken that his mother raised made a lot of noise. He glanced towards the west where a snakelike stream of fog floated over the gorge, tracing the course of the Nile River. For months, his father had complained of the little rain the region received. Mokria had wondered why they needed rain when the Nile flowed like a raging monster nearby, until his father explained: “How could we bucket enough water for the vast land?” He had told Mokria that a long time ago the Italians brought pipes and engines and pumped a little, but “they couldn’t bring enough water for a fraction of the prince’s farmland!”

Mokria’s grandfather sharecropped for a prince, his father sharecropped for the same prince’s son; and after his father dies, Mokria will sharecrop for the prince’s grandson who will inherit the land. Mokria knew that his rebellious younger brother, Gobezie, would certainly have problems serving any prince, father, son or grandson. Gobezie was unlike any of his other brothers—so rebellious that his father beat him up very often for refusing to work. “Let the prince come and work on the muddy field himself,” he would defiantly say to his father.

The previous night at dinner, Mokria had asked about the size of their landlord’s farm, the confines of the prince’s land. His father exclaimed, “Erre b’amlak! Oh God, it is a half-day’s travel on the back of a mule,” he had explained to his children.

Ten villages toiled the land and delivered the harvest on pack animals to the prince’s stores in the nearby town after taking their cut of the harvest, ten percent. The prince lived in Addis Abeba, the capital city. He had inherited the land from his father, who received it as a grant from King Minelik when he defeated another prince who owned it before him. Mokria’s father never met the prince for whom he slaved. “He is a royal prince, he can’t come to our dirty villages, and he couldn’t possibly be able to inspect the vast farmlands that he owns!” Mokria’s father had said. Gobezie had a remark: “And you do not own the land on which our hut stands!”

His father had enough of Gobezie’s rebellion—he sent him off to a nearby village, to his brother who didn’t have children of his own. But living with his uncle made Gobezie more rebellious and further poisoned his thinking.

Neither Mokria nor his father or his grandfather considered the deal they had with the prince unfair, only Gobezie did. Ten villages and nearly a thousand people lived in the land; all of them busy producing for the prince who held a high position in Janhoi’s government.

Still sitting behind the bushy fence, Mokria looked at the top of the mountain again. The clouds were becoming thinner and the fog cleared out while he patiently waited for his father. He knew it would be another tough day in the fields before he returned in the afternoon to walk to the old monastery on the side of the Wehni Mountain. Farming and church was the mainstay of his life. Every afternoon after a brief relaxation, Mokria would go to the church to study under Mergheta Kndye, the old priest who taught him how to read and write. He had begun memorizing the Psalms of David. If Mergheta thought Mokria did well, he might expose him to the secrets of Kebre Neggest, Glory of the Kings, a revered Abyssinian book of knowledge. Mokria’s father urged his son to learn the history of the great warrior kings of Abyssinia, whom he mentioned with admiration, “so powerful they could own a land surrounding fifty villages.”

He would be in a bad mood before the beginning of the rainy seasons. His father and brothers would be busy for months preparing the land that they would sow with teff crop. Weeding the muddy furrows would be next, followed by weeks of warding off the birds with the noise of pebbles crackling inside empty cans. Next, they would harvest the crops, separate the tiny teff seeds from the stems, blow away the chaff, and finally, collect it in jute sacks before taking it to the prince’s stores. The tough job would only end by mid-Meskerem, September, when the four-month season of festivities and weddings would begin. Mokria would then linger around with not much work to do except feeding and milking the only family cow.

The first few Sundays after the harvest season very enjoyable. The families would take turns holding parties, and consume lots of meat and tella beer. The chats that followed went well into the night. He would see less of Mergheta Kndye and more of his father and uncles, who would tell him stories of brave kings, princes who owned vast lands and hard working peasants who made their masters happy. He would listen and ask questions to the tipsy men who enjoyed passing to him their knowledge of ancient history.

“Janhoi is left with only half of the country… he distributed vast lands to the princes… they deserve it, but… May God give him longevity,” his father said, apparently torn apart, worried that the king’s vast land would be diminished by grants.

Mokria nodded in admiration of the king: “Only a generous king would give such vast land as a gift!”

He grew up believing the king to be just one level below God and infallible. He thought it natural for the king to own the land, God’s land. But God cannot come to earth and own it—the king, God’s viceroy, does that for Him. Unlike his brother Gobezie, it didn’t occur to him why his father or grandfather didn’t own the land.

“The troops of this prince’s father had fought in the East, and this land is his reward,” Mokria’s uncle explained, “They pillaged and enslaved many, an epic pillaging.” He would never refer to the landlord as ‘our prince’ as Mokria’s father did.

“Those Eastern people! You either defeat them or die in battle—if you are captured, a fate worse than death awaits you,” Mokria’s father said.

They all laughed.

“Why?” Mokria asked.

“If you fall in their hands, they cut your organs!”

“Organs?”

“Organs. Between your legs!” His uncle replied, pointing to his crotch.

Mokria felt a shiver along his spine and he unconsciously reached for his crotch.

He learned why Abyssinian warriors, motivated by fear, fought with courage to kill or die; surrendering to the enemy or being captured in battle had terrifying consequences. They had to win to avoid the fate of having to return home without their manly tools, not able to produce children anymore.

His uncle had said, “Our nobility didn’t value marriage highly, un-Christian promiscuity, unrestrained sexual appetite and moral decadence.” He shook his head and squinted, “They produced as many illegitimate children as they did in wedlock, the reason for the numerous claimants.”

Mokria looked towards the Wehni Mountain, to the moon shining behind the tip. He imagined young princelings detained on top of the mountain remembering the history his father recounted proudly: princely brothers killed each other or slaughtered their fathers, the kings, to seize power, and created chaos that lasted for centuries. The power struggle, the intense never-ending infighting among claimants of the throne, made Abyssinians devise a system to quell the insatiable greed for power and divine titles. He marveled at the ferocity with which the princes and the nobility fought among each other. Yet, he didn’t approve of the way his uncle debased the royalty, and worried that Gobezie would be as Satanic as his uncle, since he lived with him.

Mokria had learned that the clergy and the nobility invented Wehni-Bet, a detention village on top of the Wehni Mountain, where all possible claimants to the throne were kept until they died. The clergy detained the princes to prevent them from posing a threat to a sitting king. If the clergy and the nobility decided to have one of the princes at Wehni crowned, they brought him down. No one else but the clergy and the sitting king had access to the mountaintop.

Mokria sat outside the hut, still waiting for his father, and looked at the narrow trail that meandered to the top of the mountain, to the Wehni jail.

His grandfather had worked as a guard on the Wehni gates until they abandoned the place. He had preferred to stay behind with a few other guards, deciding to call the place home. The landlord was more than happy to have more farm hands around and allotted a space for them to set a cluster of huts. Mokria’s grandfather built a hut where the old gates stood, brought his relatives and friends to live with him, and baptized the place Wehni-Ber, Wehni Gate—Mokria’s village. Mokria felt proud for being a descendant of the proud gatekeepers to the forbidden jail of Wehni-Ber. No wonder his father named him Mokria, Pride.

MOKRIA HAD DONE WELL. Mergheta Kndye promoted him to the next level; he would now study the Kebre Neggest, a book he absorbed with excitement together with a few other boys. Mergheta Kndye surrounded the Kebre Neggest with so much aura that Mokria considered it as important as the bible. The teacher didn’t show his students the difference—maybe he didn’t see any. Neither did Mokria discover any while reading the captivating stories of kings, “stories over two-thousand years old,” as Mergheta Kndye explained. His father was right. In the book, Mokria found the mythical origin of Janhoi, straight from the veins of King Solomon and Queen of Sheba. It was there written in black ink with illustrations, colorful pictures of people with eyes so big they occupied half their faces. Here was a woman with a crown on her head lying down with open legs, a man with a crown on his head, on top of her—a painting depicting Janhoi’s ancestors fornicating! Then the two royals drink wine from golden cups after the act. King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba had just produced the future Minelik, Mergheta had told him. On the next page the Queen of Sheba headed back home to Abyssinia. Next, there is another painting of the queen giving birth to Minelik on the banks of the Maibela Creek. Mokria thought it only natural that Janhoi, the present king, should belong to such a couple and such an affair, though the painting didn’t depict the event.

Mergheta Kndye would never mention the Kebre Neggest as the work of a fourteenth-century genius, an Egyptian Coptic priest. Having grown up feeding on the same myths himself, just like Mokria, maybe he believed every bit of it.

Chaos, the defining factor of Abyssinia for too long, needed a solution, and the Egyptian priest had come with a rescue. He produced a perfect myth, he authored Kebre Neggest, Glory of Kings—a lore on whose pages retroactively created legends fit together like bricks in a wall—to explain the present and stabilize the future. It connected the bloodline of the many Abyssinian kings, the Janhois, to that of Solomon, the Israelite king.

The Kebre Neggest, initially written in Arabic, had been translated into Geez, the language of the Axumite Kingdom, the only kingdom that created an indigenous African alphabet. This was long before “Solomonic” kings usurped legitimacy to the throne—long before the Kebre Neggest was conceived, impregnated with a mish-mash of fables, generously sprinkled with scriptures from the Bible and the Koran, and embellished with ancient pornography—retroactively producing a mythical king, Minelik, son of King Solomon, so that future kings including Haile Sellassie, the Janhoi, could claim a title, Elect of God.

Apparently, the Solomonic bloodline had disappeared midway. It had been eradicated from Axum and replaced by the Zagwe Dynasty that ruled Abyssinia for decades. But not before one keeper of the gene had escaped with Solomon’s blood in his veins, according to the fables of Kebre Neggest. The bloodline survived in Shoa for centuries and reappeared in the veins of Yekuno-Amlak, a Janhoi who suddenly came to the picture thanks to the consultation of the Kebre Neggest. The clergy crowned the lost gene-carrier King of Abyssinia on a throne that a Zagwe king abdicated voluntarily, according to the Kebre Neggest; he must have considered his blood less worthy than a Solomonic progeny. The Zagwe king, offspring of the great architects and builders of the rock-hewn churches of Lallibela, abdicated to the lost-and-found peasant Yokuno-Amlak. But Mokria never questioned the fables.

He trusted the Kebre Neggest which said that centuries later, again, some king by the name of Sahle-Sellassie magically proved his Solomonic DNA. As designed, the Kebre Neggest’s attempt to put an end to the power struggle among the nobility, to establish a legitimate condition to assume the throne, succeeded. Janhoi Sahle-Sellassie became the king of Abyssinia. Of course, Haile Sellasie could also plump a bloodline. He did. And he became Janhoi.

Gobezie saw it differently. He considered the Kebre Neggest a mythology that was elevated to the status of a canon and a religious doctrine, came with a great expense and had a profoundly negative effect on the non-Christian people of the region. It immersed Abyssinia into a fanatic theocracy. It crippled scholarship. It blocked enlightenment. It established the absolute power of the church over the state. Abyssinians barricaded themselves in their mountains for centuries, and every time they peeked to the outside world, they found themselves lagging far behind. Giving up on advancement, they retreated, back to the mountains, back to isolation, and engaged in their favorite pastime: bloodletting and pillaging. They effectively built an isolation wall around their country.

Unlike Mokria, Gobezie had learned about it from the perspective of his rebellious uncle, not from the perspective of his father or Mergheta Kndye. Thus, the two brothers were molded into different characters. One looking to the open space and wistful that his country would enjoy justice and fairness, to grow wings and fly; another looking at the Wehni mountaintop, the prison, and wishing he could roll the entire country and quarantine it there, and he, Mokria, would stand guard from where his grandfather stood.

GOBEZIE LIKED THE MISSIONARY SCHOOL in the town nearby, it helped him expand his imagination. Brilliant and an over-achiever, he surpassed older students and gained the admiration of his teachers. He read many books and became more critical of everything around him, and discovered there was knowledge beyond Mergheta Kndye’s tree-shade. Every time he met Mokria, they argued. He would say, “Half a day on a mule back to the limits of one prince’s land! Then equal distance before you reach the end of the Church’s land.” He would shake his head and add, “You travel for weeks before you find a peasant who owns his land!”

“Seytan!” Mokria would snap, “What else does a farmer need? We are living off Janhoi’s land.” He would chastise his younger brother, “You know nothing!”

At an early age, Gobezie recognized that the dynasty that ruled Abyssinia for centuries had nothing to show for the long history.

“You like it this way, Mokria? Our grandfather and now our father delivering their harvest on borrowed donkeys to a prince they never met?”

“Tsere Mariam! The Whites are corrupting you. I heard of your mingling with the missionaries, they are corrupting you just like they corrupted our uncle!” Mokria would frown.

Gobezie knew Mokria’s problem. His uncle had told him of the zealotry of the Jesuits, “serpents! They wanted to baptize the already Christian Tewahdo!” He had said.

His uncle had picked on the Jesuits for the outrageous things they did to the Orthodox. He didn’t like all the zealot missionaries who he thought had gone awry. “Europeans had spread their medieval religious intolerance and introduced fanaticism to Abyssinia. Even Egyptian Copts had brought their hate of Muslims,” he explained, “they wanted to get even with the Arabs who overran their country.”

The missionaries transformed Abyssinia into a confrontational arena between the Abrahamic religions, and the chaos produced a ruling class that thought life was all about wars and invasions. A brutal cycle of power struggle and palace intrigues followed and it disrupted the lives of the poor peasants for centuries—the never-ending state of war became normality.

Gobezie believed only a revolution would end the archaic regime; he had lost hope in its reformation. He believed that a new era of enlightenment should be built on the ashes of the feudal regime. But Mokria had another solution in his mind; he wished to crush anyone who challenged the king, the symbol of Abyssinian rule and pride. The old belief had firmly ingrained itself in Mokria’s mind and he prayed to see Janhoi act like King Tedros. He believed Janhoi was more than fit for that role, if only the white snakes, the cunning Europeans, would leave him alone.

A hundred years and four emperors before Janhoi, another ‘king of kings,’ Kassa of Qwara had attempted to find a stain of Solomon’s blood in his veins. Though the nobility considered him a usurper, he forced an Egyptian bishop to crown him emperor and confirm his Solomonic blood. He picked a crown name for himself, Tedros, a name of an awaited legendary king who, according to the Kebre Neggest, would deliver Abyssinia out of the bloody age and launch an era of prosperity. He fitted the myth of the long awaited king under whose rule the Abyssinia Empire would eclipse the might of the Romans!

Gobezie heard from his uncle that a century earlier, Queen Victoria of England angered Tedros and he retaliated by taking her emissaries, missionaries and other British subjects, hostage. Mergheta Kndye had told Mokria one version of the story: “The queen didn’t respond to Tedros’ letter and that angered him—it is disrespectful!”

His uncle’s version said, “Tedros had proposed to the Queen in the letter and she had rejected him. That angered the king.”

Mokria wondered why Tedros would want to marry a white woman, “Why would she refuse a king’s proposal? Ambetta!” He fumed and insulted the queen as ambetta, locust; he considered white skin as pale as the color of locust.

Tedros had put himself in a bad situation by taking hostages and jailing them in Meqdela, his hilltop capital. Gobezie had passed by that village on his way to Addis Abeba with his uncle.

The Queen of England had dispatched Rassam, a British subject of Iraqi origin, to negotiate the release of the hostages, but Tedros took him hostage as well, and wouldn’t budge. Unknowingly, Tedros had called for an invasion of his country by the British army—probably the first military invasion of a country to free hostages in modern times.

An expedition under the command of General Napier arrived from India and landed at the Red Sea coast, at Zula, ancient Adulis. They built a railway to Segeneiti on the plateau beyond, passed through Tigrai in northern Abyssinia with the full cooperation of Degiat Kassa, a warlord of the region, and marched with elephants, mules and horses, all the way to Meqdela, Tedros’ straw-hut dotted capital city. They attacked it. Tedros’ prized-weapon, the cannon he forced his hostages to fabricate and which he baptized Sevastopol, failed. Angry, the erratic Tedros pushed hundreds of his soldiers over the cliffs to their death, a punishment for not fighting gallantly, for failing to defeat the invaders. He barricaded himself on the hilltop; the British soldiers stormed Meqdela, went straight to Tedros’ tent and found him dead. He had swallowed a bullet from his own pistol, a gift from Queen Victoria in better times. General Napier had reversed course and headed north with his invading army, towards the Red Sea. Gobezie’s uncle wondered: “Any place the Europeans invaded, they stayed as colonizers; the British expedition didn’t occupy Abyssinia. I still do not understand why!”

On his way back to the Red Sea, Napier armed Degiat Kassa to the teeth with thousands of rifles and ammunition—a reward for his cooperation with the expedition against Tedros. Degiat Kassa became the strongman of the region, he assumed Tedros’ throne and named himself King Yohannes IV, another Janhoi. A little over a decade into his rule, the Italians established a colony on the cost of the Red Sea and named it Eritrea. Soon, Yohannes died fighting the Mahdi of Sudan.

Following the death of Yohannes, Menelik II, an Amhara king, named himself king of kings. He spread his authority to the north and stopped at the border of the Italian colonial territory, Eritrea. He headed east, pillaged the Harrer and the Ogaden regions, and stopped only when he reached the confines of European-controlled areas of Kenya, Somalia, Djibouti and Somaliland. Menelik II, a namesake of the first Minelik, the mythical son of Solomon, the one born in Maibela, had built his empire on the bones of many people; and in that, he surpassed the brutality of Tedros and the fanaticism of Yohannes.

WHEN MOKRIA WAS SEVENTEEN, his two younger brothers had become old enough to do all the farm work. Besides, the landlord had sent a family of five to work part of the land that Mokria’s family worked on and all the land on which his uncle farmed. His uncle had seen this coming; he had abandoned the life of a sharecropper and moved to the capital. He had taken Gobezie along and enrolled him in a secondary school. Gobezie was so smart that the school director had advanced him a year. His uncle, thanks to his enterprise, had quickly become a grain wholesaler. It didn’t take him long to be established in the city and he promised to send Gobezie to a private school even just for his final year—maybe Wingate, or that French school!

Having finished his studies under Mergheta Kndye, Mokria had briefly entertained the idea of becoming a priest in a remote monastery; he saw a different life for himself now that his younger brothers had become adults. But then he heard of a recruitment by the army. He thought he would have an opportunity to defeat the Roman Empire as the Kebre Neggest prophesied. His father approved of his son’s decision with happiness. Mokria trekked to the nearest town and enlisted. He would be a well-trained soldier in a year.

He had found a corner for himself behind the cabin of the military truck and joined many young farmers from the countryside on the five-hour drive to the training camp. One year seemed a long time but soon, Mokria realized the training period had passed quickly—he learned marching, shooting, handling grenades and an M14 rifle. A trained soldier, he stood in line with hundreds of young country boys in the graduation ceremony. The commander congratulated the batch for a successful training and pumped into them patriotic zeal that should be translated by loyalty to the king. In his speech, he explained the challenges ahead: the bandits are challenging Janhoi’s government in the North and they must be crushed. The officers avoided mentioning Eritrea as if a vulgar word and referred to it by its direction, the North. “Throughout the last four years we have been patient, now the bandits of the North have to be crushed without mercy,” the commander had said.

Mokria still had that one task he wanted to accomplish in his lifetime—eclipsing the Roman Empire. He had no idea the Roman Empire had collapsed almost two-thousand years earlier. His brother Gobezie would have reminded him, but by then he had gone away with his uncle.

“Are they Roman bandits?” Mokria asked the soldier on his side in a whisper. The soldier laughed, almost attracting the attention of the commander.

Mokria became the joke of the camp and the troops made fun of him; that angered Mokria so much that he punched a soldier who laughed at him. It took five men to separate them. Later that night he learned that, “Muslim bandits are trying to sell Janhoi’s Red Sea Coast to the Arabs.” He found solace remembering Mergheta Kndye who had never missed an opportunity to mention Janhoi’s greatness to Mokria. “All the Whites bow their heads for him,” he had said, “He drove the fascists away and freed the country.”

“Yetabatachew Areboch! We have to stop the damned Arabs,” Mokria was enraged.

Having completed his training, the officer told him that he would be stationed in Keren, in the North, after spending a four-week leave visiting his parents before packing for Eritrea.

He traveled for three days, walking and hitch hiking on lorries for short distances and walking again until he finally reached Wehni-Ber under a drizzle. Clad in green military uniform, leather boots, and a military sack, he walked towards his parent’s hut feeling as proud as one of the ancient warriors in the many stories that his father told him about. It felt like years since he left his village, walking the trails made him feel like crying in happiness. He spotted his mother from a distance as she milked the family cow. Mokria shouted, mother: “Emayeh! Emayeh!”

His mother didn’t recognize him at first, but as he came closer, she recognized the very soldierly son of hers. She dropped the bowl she carried and ran to meet Mokria. They hugged and kissed each other for a long time. She stepped back several times to inspect his uniform, admiring every piece on his body. Mokria followed his mother to the hut; she ululated loudly, attracting the attention of the village women who peeped through the doors of their huts to find out what was going on, and they joined the ululation as they discovered the warrior of the village had returned home.

Mokria’s father and his brothers had not returned from the fields. Until they returned, Mokria busied himself drinking tella and eating injera left over from the previous day—he had missed his mother’s cooking. Soon his father arrived and saw Mokria. He dropped the sickle that rested on his shoulder and embraced Mokria. “Endie! You have grown up immensely, what were they feeding you?”

“It is what you already fed me father, the camp food is tasteless bread and canned meat; I suspect it is not beef as they claim!”

“You have high shoes, endie! And a jacket! Ererere, and a wide belt!”

They talked until late that night. A lot had changed in his absence. Gobezie had gone to college; his uncle didn’t manage to get him to a private school. Now he promised to send him abroad for graduate studies once he received his degree.

FOR THREE WEEKS THEY PAPMERED Mokria at Wehni-Ber. Now he had to return to the camp and join his battalion on his way to Eritrea.

The convoy drove through treacherous mountains, over bottomless gorges and bridges that Mokria thought would collapse anytime. For three days he had been on a meandering dirt road that seemed to drop from one mountain to a valley and abruptly climb to yet another mountain. Countless streams briefly interrupted the green landscape. He then reached a bald brownish region, the landscape got drier and the vegetation slowly disappeared. From a distance, he could now see small structures with shinning metal roofs; he discovered they would soon reach the town of Adua. This is where we defeated the Fascists, Mokria thought. He felt proud. Even his uncle and his brother Gobezie felt proud of that battle, the Battle of Adua, probably one of the few things they agreed about. Now that there are no more European fascists in Eritrea, but only bandits, they should be defeated, just as the Abyssinians defeated the fascists at Adua. “How far to Korem?” Mokria asked his sergeant.

The sergeant laughed, “We passed Korem hours ago. We are going to Keren, with an N, not Korem.”

After a short stop, the convoy rolled on and reached the Mereb River.

“Is this Maibela?” Mokria asked.

No one responded. Mokria guessed it was not.

They arrived in Asmera early in the morning and pitched tents in a field close to the main garrison. They were free for the day. Mokria found a distant relative, a sergeant who showed him around. “Take me to Maibela,” Mokria asked. They walked there.

He knew from the Kebre Neggest that the Queen of Sheba gave birth to King Minelik in that creek, Maibela. Now, three thousand years later, Mokria found it to be a sewer carrier, and nothing like the rivers he knew—he had something close to the Nile in mind. He had also expected to find a shrine in the holy place, there was none. In shock, he clamped his nostrils with his thumb and index finger.

“How could a queen give birth in such a dirty place?” He asked the sergeant.

“This is the refuse of the White people of the city, their droppings. When the Queen of Sheba passed through here, the water was as clear as silver—no White droppings, not even native urine.”

Mokria met his first true disappointment. He tried to imagine what else he had learned in the Kebre Neggest that might turn out to be a disappointment.

“Minelik was born here?” he asked disbelieving his eyes that the renowned Queen of Sheba would have given birth to the son she bore from King Solomon in that dirty place.

“Enjalet! I don’t know! Minelik is not even his name,” the sergeant replied. He must have been properly initiated and went through the shock well before Mokria came.

That was Minelik I, who, according to the Kebre Neggest, was supposedly born there three thousand years earlier.

There was Menelik II who claimed to be the descendant of Menelik I and who died some fifty years before Mokria saw the original Menelik’s birthplace, Maibela.

Few palace dramas followed the death of Minelik. His daughter Zewditu succeeded him and her nephew Iyassu, succeeded her. But the clergy and the feudal lords accused him of having Muslim sentiments and deposed Iyassu, the son of Ras Ali, whom Yohannes defeated, converted and Christened Michael, who had married Minelik’s daughter who gave birth to Iyassu. The marriage was a deal to make sure Ali doesn’t one day remember he was Ali and revolt against Minelik.

In a similar deal, Mennen, Michael’s mother, was married to two kings, and she had given her daughter to Tedros to keep him on a leash. That failed. Then, another great-nephew of Ali/Michael, another illegitimate son, the brutally notorious Wube, had challenged Tedros’ control of the throne but he failed.

Iyassu became a victim of his recklessness as well as his brutality—he had enslaved thousands of Oromos before he left to the desert and started to flirt with his Muslim cousins. The nobility and the clergy replaced him with another claimant to Solomonic blood, Ras Tefferi, who they crowned Emperor Haile Sellasie, literally “The Power of the Trinity,” or more colorfully, “His Majesty, King of Kings, Elect of God, The Conquering Lion of Judah, Emperor Haile Sellasie 1st.” Janhoi, short for the seventeen word title.

“What? What was his name then?” Mokria was curious.

“It was Ibn’l Malik or Bin Melik, Arabic or Hebrew meaning the king’s son. Our captain told us that—he is educated and has books, he knows many things.”

Mokria wondered if the captain was not impersonating his brother Gobezie—he sounded like him. ‘Would Mergheta Kndye lie to me?’ Mokria wondered, still not bold enough to question the validity of the Kebre Neggest fables; yet he blamed Mergheta Kndye for not telling him that in Eritrea, they desecrated the birthplace of Minelik. He was angry at the captain who suggested Minelik’s name was not an original Abyssinian name, and that it could be Arabic or Hebrew. Aren’t the Arabs bidding to buy Eritrea from the bandits? Aren’t they the ones who want to take Janhoi’s Red Sea? The Red Sea that has always been the gate for the invaders who attacked Abyssinia? Didn’t English Whites come through it to kill Tedros? Janhoi should not let go of the Red Sea; Mokria promised himself to fight and defeat the bandits in the North, the Land Beyond the Mereb River. He promised himself to pacify The Land of the Sea.

Awate Forum