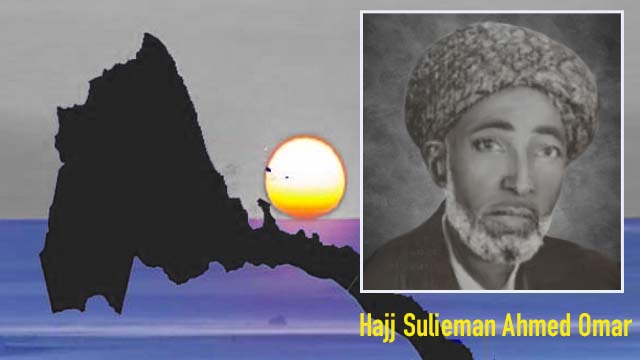

On the 50th Anniversary of a Founding Father, Hajj Sulieman Ahmed Omar!

On a typical quiet day in Asmara, hours before the sunset, a group of men came to our home, located on Leonardo Da Vinci Street. None of the men were familiar to me, except for one. He was the tallest among them; he was wearing a colourful turban, a white Jalabia and a classic coat on top. His facial expressions were calm and his demeanor imposing. He was Hajj Sulieman Ahmed Omer, the elder brother of my father, Sheik Ibrahim Al Mukhtar. At this time, he was a political prisoner, but the way he was dressed at that moment didn’t sound like a prisoner. The group was welcomed by my father, and they proceeded to the living room, where the doors were firmly locked. Hours later, the group departed, as quickly and quietly as they came; and days after, Hajj Suleiman was released.

I am not privy to the discussions that took place in the meeting, but I had heard it was a negotiation for a conditional release of Hajj Sulieman with my father acting as a guarantor. Prior to this, I had once accompanied my relative to a prison to deliver food and clothing to Hajj Sulieman. We were received by an officer who took us to where Hajj Sulieman was imprisoned, as usual, we found him determined, dignified and resolute.

This was the Hajj Sulieman I remember, a man who spent his life in and out of prison, a man under round the clock surveillance, regular police interrogation and intense investigation. He was one of the few remaining unwavering founding fathers of the Eritrean independence movement. Many of his comrades, such as Ibrahim Sultan and Woldeab Woldemariam have left the country, others such as Abdulkadir Kebire were assassinated and a few others kept a low profile. The Ethiopian government followed the carrot and stick policy with him, hoping to win him over, but the Hajj stayed the course. He was resolute in his belief that freedom -“Hurria”- (حرية) was coming. “Hurria” was his passion and his dream; he spoke about it everywhere, and even named his eldest son’s first daughter “Hurria”. Before his death, he told some of his acquaintances: when Eritrea gains “Hurria” come to my grave and loudly announce the glad tidying to me!

The journey from “Naba Gade” to Asmara!

Hajj Suleiman grew up in a remote valley known as Naba Gade (meaning huge cliff in Saho language), and it was among this rugged terrain that he spent his youth, much like any other rural boy – farming and shepherding animals.

He was the eldest of his family. His father was a learned scholar who studied abroad. Being a son of a scholar, he had the privilege of receiving advanced learning in Arabic and Islamic Studies. From the early stages in his life, he was ambitious and daring; the life of a farmer or a shepherd in a remote area wasn’t something he aspired to do. He soon departed to the nearby city of Adi Keih in search for better opportunities. Transitioning to city life was challenging. Venturing his way, he began selling simple items and as his profit margins grew, his business expanded, earning him a reputation in Adi Keih as a well-to-do entrepreneur. For the Hajj, being a businessman was a departure from the scholarly path of his father and many of his ancestors. However, the Hajj tried to strike a balance between the two paths and sought the company of a learned scholar. Fortunately, he found in Adi Keih, a scholar of his father’s caliber, perhaps the first Eritrean to travel to India and graduate from the Deoband Islamic University, Sheik Muhammad Saleh Al-Abreeaoui. Thus, having succeeded in his business endeavors, he began to devote some of his energies to scholarship.

Hajj Sulieman’s business expanded to reach to Massawa and across the Red Sea to Arabia and eventually to Asmara. With his business growing and thriving, he decided to move to Asmara, the capital. The Hajj took interest in the real estate market and acquired large expanse of real estate property. Eventually, he became part of the merchant elites in Asmara, befriending many of the notables in the city. This was certainly an impressive leap for a man who came from a remote area, who barely spoke any language other than Saho and some Arabic.

My country comes first!

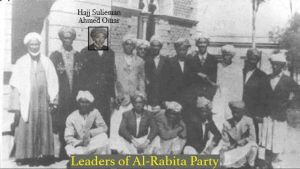

The end of Italian occupation, and subsequent arrival of the era of British administration over Eritrea, sparked an intense political debate among Eritreans. Two major and one minor faction emerged. The two major factions were the Unionist faction, which called for the annexation of Eritrea to Ethiopia, and the Independence faction, which called for Eritrea’s independence. The third faction called for splitting Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia. The Bet Giorgis conference, held in the outskirts of Asmara in 1946, was the last hope of reaching a national consensus on Eritrea. Following the miserable end of the Bet Giorgis conference, it became crystal clear that a national consensus was unachievable. Accordingly, the key leaders of the independence movement started planning for the official launching of the first pro-independence party, the Al-Rabita -the Muslim League in 1946. It was amidst this whirlwind of change that Hajj Suleiman was transformed from a businessman to an ardent, nationalist politician.

Typical to his personality, the Hajj preferred to be away from the spotlight and do the legwork behind the scenes. Hence, his role was less visible, but very significant. Prior to the launching of the first conference for the establishment of the League, he along with the other pro-independence notables were the key coordinators. He became a founding member of the Supreme Council of the League.

Hajj Sulieman played important roles in many ways. Given his wide-ranging business networks, he was instrumental in reaching out to tribal leaders and rallying them behind the League. The Hajj also had keen interest in constitutional matters and played important roles in preparing legal and organizational documents for the group. He was the primary architect of the proposed constitution designed to form the basis of an Eritrean government -made up of 173 articles-, which was presented to UN representative in 1952. Unlike the Unionist party, which was financially supported by the emperor Haile Selassie, the League was dependent on local donations. Hajj Suleiman, and many others from the nationalist merchant elite, contributed enormous amounts from their personal fortunes. It is believed he in particular liquidated a significant portion of his real estate assets in order to aid the League.

In 1947, he, along with five others from the League’s Executive Council, appeared before British, French and American delegates in Asmara to argue for the independence cause. In 1949 the Hajj was part of the delegation that traveled to New York to make the case of Eritrean independence before the UN. During the first parliamentary Eritrean election in 1952, following the Federation Act, the Hajj was asked to run for the seat representing his region on behalf of the League. Befitting his personality, he stated he did not wish to run in a contested election and would only serve if no others decided to step forward. He continued to contribute behind-the-scenes into the parliamentary era, and was one of the key supporters of the pro-independence MPs. Given his expertise in the customary law, the parliamentarians elected him to be part of a committee responsible for compiling the customary laws in Eritrea. His deep involvement in the national cause came at the expense of his business, which suffered a lot. But for the Hajj, his country came first, and his personal wealth was a small sacrifice if it meant achieving the dream of his country’s Hurria.

Under the jaws of the tyranny!

Following the practical take over of Eritrea by the Ethiopian government and the repression that followed, the Hajj came under intense scrutiny. As one of the few remaining active leaders of the independence movement, he soon became the target of the continuous government surveillance. The Hajj was a signatory to many letters and memorandums sent to the UN, the emperor and various officials defending Eritrea’s sovereignty. In 1957, following Ethiopia’s continued violations of the UN federal resolution, he along with the few remaining leaders of the League, issued a telegram to the UN, calling for UN to intervene and stop Ethiopia’s violations. As a result, he, and Hajj Imam Mussa, one of the leaders of the League, were charged and sentenced to four years in prison and strangely, even their lawyer, Gebre Loul, was sentenced for three months! The Hajj was 60 years old at the time and Imam Mussa was 81; both were jailed in the notorious prison of Adi Khuala. After his release, he was imprisoned a few more times, including his imprisonment in 1967. This came following a meeting he led with the emperor Haile Selassie, where they submitted a petition calling for upholding the federal constitution, including the teaching of Arabic language. Despite the emperor’s promise to consider the demands, the Hajj was immediately imprisoned again. After his release, later he was imprisoned again, following a telegram he sent on behalf of the League to the president of Egypt. He was arrested and shipped immediately to a distant prison in the port of Assab.

In these years, the Hajj’s life of intermittent imprisonment continued unabated. Few times, he was released by the appeals made by various elders and notables in Asmara. Even outside the prison, the Hajj was a virtual prisoner. He was banned from leaving Asmara, he was followed by spies in all his movements and regularly called for questioning. Despite all of these, the Hajj found ways of eluding the spies and communicating with the emerging resistance movement. As confirmed by Saeed Nawed, the founder of Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM) commonly known in Tigrinya as Mahber Shouate (ማሕበር ሸዉዓተ), Hajj Sulieman was one of its secret members inside Eritrea. No matter the hardships and threats he endured, the Hajj never entertained the idea of leaving the country; he was determined to the stay the course no matter the cost.

Remarkable partnership!

Hajj Sulieman and his younger brother, Sheik Ibrahim Al Mukhtar, the Mufti of Eritrea, were more than just siblings. They both shared a deep passion for the nationalist cause of their nation. Sheik Ibrahim, being the Mufti of the country, had limitations on any public political engagement, but he was an ardent supporter of the independence movement, which he expressed clearly to the UN representatives and to various leaders of Eritrean governments. The Mufti was under pressure from the state to stop his brother from working against the government, which he never did. Partners in the cause, they both complemented each other. The Mufti had deep scholarly credentials from his studies in Al-Azhar, plus deeper understanding of global issues as a result of living in Egypt, the intellectual epicenter of the Middle East, for fifteen years. The Hajj, on the other hand, had deeper knowledge of the customs, tribes, and day-to-day issues in Eritrea plus a widespread social network. As a result, both brothers played a pivotal role in the struggle to secure the Hurria of their people; the extent of which has yet to be divulged by historians and researchers.

The Mufti describes his brother as his mentor, who not only supported him in completing his studies in Al-Azhar University but advised him on how to navigate through the intricacies of the Eritrean society, as the newly appointed Mufti of the country. The Mufti describes Hajj Sulieman as follows:

“He was profoundly foresighted, well rounded, very confidential, patient and not hasty. He wouldn’t speak in public gathering before listening to the opinions of others; he was very cautious not to hurt the feelings of others and when he spoke, his words were unifying and consensus building.”

Through out the years of the struggle, the Hajj was a unifying voice. As early as 1947, he reminded Eritreans in the June 1947 pro-independence rally in Asmara, that Eritrean independence couldn’t be accomplished without the unity of Eritrean citizens. The unifying voice of the Hajj and other visionary leaders of the League was instrumental in the League’s early effort to coordinate with the pro-independence Liberal Party, led by Ras Tesma and the establishment of a common flag and a common platform.

The Hajj was a self taught, avid reader and well-rounded personality. His constant bed-side companion was his radio, by which he followed the daily news and political events across the globe.

Final years

In March 1971, Hajj Sulieman passed away, two years after his brother. Both brothers were buried side by side in the Haz-Haz cemetery in Asmara. The last few years were difficult for the Hajj. The loss of his brother and partner in the struggle, who died in what some people think was suspicious, was difficult for him. Years of struggle, imprisonment and continuous harassment by the state have taken a toll on him. He left the world without seeing the “Hurria” that he had long dreamt of, but he left certain it was coming one day!!

References:

https://mukhtar.ca/

حركة تحرير ارتريا: الحقيقة والتاريخ ناود محمد سعيد،

Venosa Joseph (2014), Path toward the Nation…

Awate Forum