Eritrea’s New Capital And Social Control through Currency Change

Countries usually announce change of currency to (a) stabilize a wobbly banking system, (b) to fight hyper-inflation, (c) to opt for currency substitution due to joining a regional or international currency or (d) to assert sovereignty. On November 3rd, the Eritrean regime announced that it will be issuing new currency and that Eritreans have six-weeks to surrender old currencies in exchange for new Nakfa at a 1:1 ratio. Four reasons have been given—officially and semi-officially—for this decision. They are (1) to fight the black market; (2) to fight inflation; (3) to increase currency circulation; (4) to fight contraband and corruption. This poses the following questions: Are the measures it is taking adequate? If they are not adequate, why, and what must be done? This is what we will try to address in this editorial. But to help us all understand where we are, we need to begin with the state of Eritrea’s economy.

Since the government has no published budget and no reports (or reporting mechanism), Eritreans often rely on international financial institutions to understand the state of the economy. The problem is that the financial institutions, themselves, give wildly varying numbers. Three years ago, the pro-regime websites couldn’t get enough of the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) forecast that Eritrea’s economy would be among the fastest-growing in the world for 3 consecutive years. But of late, even those with bullish forecasts, like AfDB have tempered their forecast. Another problem is that some of the reports are lagging and infrequently updated.

I. GDP Growth

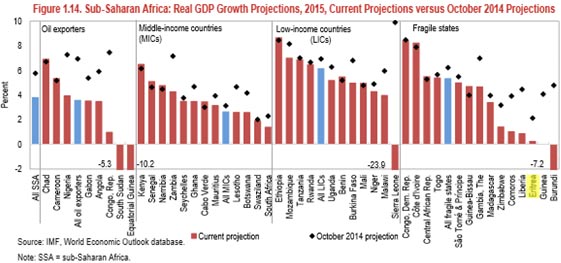

For GDP growth, we will use that of the International Monetary Fund: Real GDP Growth Projections for 2015. According to IMF, the revised growth rate for Eritrea is estimated to be 0.2%. We realize that the IMF is not popular with some segments of Eritrea—we are using it because it updates its forecasts frequently. Those who are skeptical of the IMF (because, according to pro-regime websites, a senior Ethiopian at the bank manipulates the data to make Eritrea look bad) can reference the World Bank and the Africa Development Bank. The IMF categorizes states as oil exporters, middle income countries (MICs), Low Income Countries (LICs) and Fragile states. Along with Liberia, Comoros and Zimbabwe, Eritrea is a member of the four fragile states club which will experience a less than 2% GDP growth—mostly due to drop in copper prices, its single export—for 2015; catastrophic for a nation whose population is growing at 3% annually.

What is even worse is that GDP is calculated by using the USD equivalents of Nakfa at official exchange rates. According to the World Bank, Eritrea’s GDP for 2014 is USD $3.858 billion. Let’s now see what happens if we are to use the real (market) exchange rate: it would be $3.858 * $15 (official)/$60 (unofficial). That is: Eritrea’s REAL GDP is ¼ of what is published: it’s less than $1 billion USD. This takes us to the second issue: black market.

II. Black Market

One of the reasons given for introducing the new currency is to bring to control the black market. The real question is: why is Eritrea one of only eight African countries that has a fixed exchange rate? The rest of the world has moved to a market (floating) exchange rate and has virtually eliminated the black market. Some economists (like Friedman) have also argued that a country that has a floating exchange rate does not even need to have reserves. However, following the 1998 financial crises in SE Asia, many countries maintain high reserve of US dollar and Euro to fend against currency manipulation. Moving away from the fixed exchange would eliminate the black market in Eritrea and give the bank’s coffers much-needed hard currency. Issuing new currency only kicks the can down the road—after a short period, the black market will come roaring back. We can only assume that the reason the government sticks with the fixed exchange is because it wants to manipulate the size of its GDP, and to have hard currency that exists in a parallel market—also controlled by the ruling party. That is, the black market exists to allow the ruling party to dominate the economy, to maintain a cloak of secrecy and to avoid any transparency or accountability.

III. Fight Corruption

According to Transparency International, Eritrea ranks 166 out of 175 countries in the least corrupt ranking. Put another way, there are only 9 countries that are more corrupt than Eritrea now. What is even worse is that the rank has been steadily getting worse since 2010 moving from 123, to 134, to 150, to 160 and now 166. Corruption is measured by the perception of the public sector. This suggests that corruption is endemic and part of the public sector culture now, not the least of it being due to income disparity between the haves and have-nots (one of the highest in the world) and that public sector employees do not have livable wages. In fact, it is hard to imagine how an Eritrean who has no Diaspora support can make a living in Eritrea.

IV. Inflation

Eritrea’s inflation rate has varied between the extremely high recorded in 2009 (34.70) to the high recorded for 2014 (11.6%.) In fact, only four African countries—Central African Republic, Ghana, Malawi and South Sudan—have markedly higher inflation rates than Eritrea. This, no doubt, is tied to shortage of goods and inflated money supply.

Money supply, also called M2, is the sum of “currency outside banks, demand deposits other than those of the central government and the time, savings, and foreign currency deposits of resident sectors other than the central government.” Basically, it is cash and cash equivalent that is highly liquid. M2 is measured as a percentage of the nation’s GDP. Eritrea’s M2 is 115.6% of its GDP. Recall that Eritrea’s GDP (at the official exchange rate) is $3.86 billion USD. This means its M2 is $3.86*115.6% = $4.46 billion. That is, again using the official exchange rate, 62.44 billion Nakfa that is circulating in Eritrea. That is how much new currency will have to be issued from a 1:1 exchange. To be sure, there is no absolute rule that says that high M2 leads to inflation—in fact some of the most dynamic economies (China, Hong Kong, Japan) have high M2. There is a consensus, however, that high M2, coupled with shortage of goods, with no budget constraint, or sound monetary policy is a contributor to inflation. Because of lack of available data, we are unable to run basic econometric models to analyze the impact of these macroeconomic variables on the Eritrean economy.

V. Contraband

Where there is a shortage of goods—and government policies that create shortage of goods, as is the case in Eritrea—contraband will thrive. For the last year that data is available, 2012, Eritrea’s Balance of Trade (trade deficit) was $461 million. This is because after 2010, with Bisha mine going to production, Eritrea became a one-commodity-export-economy, whose bulk of GDP is generated by one mining company.

Its import of a variety of essentials—equipment, wheat, pasta–is more than double the export. Coupled with this is the Party competing with the Government and the People: with the government issuing ill-advised and wrong decisions that empowers contraband trade, which is controlled by the ruling party.

VI. Conservative Banks

One of the arguments made for changing the currency is that the government wants to introduce a culture where people use all the tools of modern banking including checks and electronic cards. There are two problems here. Firstly, for the most part, Eritrea’s banks—just like the rest of its institutions—are not managed by technocrats but political hacks. Secondly, and related to that, Eritrean banks have one of the lowest loan-to-deposit ratio. Let’s look at both.

With a dysfunctional central bank, Eritrea’s monetary policies are not formulated to stabilize the economy and create trust; they are created to ensure that the regime’s’ coffers are the main beneficiary as a way of perpetuating its rule. For decades, that policy has created a stagnant economy resulting in unemployment, inflation, and poverty–the symptoms of bad fiscal and monetary policies and a reflection of a lack of management of money supply and the underlying problems associated with it. Consequently, a parallel unofficial economy flourishes, which encourages and rewards contraband, human trafficking and smuggling, currency black market, money laundering, and corruption at the highest levels, especially by the high ranking military officers who are involved in all sorts of illicit activities. Even Canadian mining company Nevsun engages in a militarized commerce in which the regime provides them with free labor, security protection, and transportation for hard currency.

A 1997 interview that was conducted with Berhane Abrehe, the former minister of finance, Weldai Futur, the IMF loaned consultant, and Girma Asmereom, the then-upcoming PFDJ diplomat, shows the big gap between what was promised by the Eritrean government, and what has transpired. Berhane Abrehe explained the issue of currency in a professional manner; Weldai Futur emphasized the differences in the approaches of both the Eritrean and Ethiopian governments; meanwhile, Girma, who has no training in the field, kept emphasizing how the Eritrean government wants to encourage free trade, and that it does not want to tell traders how to conduct their business transaction, sprinkling his statements with high sounding words like “globalization” and “free trade”. Time proved that those terms are alien to the PFDJ regime which was never for free trade, nor for relaxing its grip on the economy, but always focused on suffocating the business community, which it sees as a competitor not as an engine that powers the national economy the regime is supposed to manage. In hindsight, we now know that the PFDJ was opposed to Ethiopia’s insistence of using LC, (Letter of Credit) to document trade transactions because it had every intention in engaging in illicit cross-border trade to benefit PFDJ business enterprise and not the Eritrean people– a position that contributed to the 1998 war. Having failed to deliver peace and prosperity, Eritrea’s sole legal party is now insisting on trying to document and control all financial transactions of its own people. And by doing that, it will further damage the already crippled economy.

The banks which are run by political appointees—which is to say, personally by Isaias Afwerki—are, in turn, not in the business of serving their depositors—the people—but Isaias Afwerki and his Party. For 2013, the last available report, the loan-to-deposit ratio of Eritrea is 23.3%. To put this in perspective, only South Sudan had a lower ratio of 15.2%. That is to say, for every $1,000 in deposit, the Bank only lent $233. To put this in perspective again, the median loan-to-deposit ratio for Sub-Saharan Africa is 87.2%. In short, Eritreans have no incentive to go to the Bank as it is unlikely to extend credit to them. Even those who could put their properties as collateral for loans simply cannot do any kind of business because of the chronic shortage of goods, stagnant economy, and inability to compete with PFDJ business enterprises. And if it did, there are no investment opportunities and whatever little opportunities there are, they are reserved for PFDJ conglomerates. And now, with a fiat, the government wants to change people’s behavior without offering an incentive for them to do so.

Recommendations.

Under a normal government, the antidote to the underlying cause of the challenges Eritrea faces are rule of law, good governance, administrative competence, transparency, well-functioning media to inform the public in exposing corruption, and free and meaningfully regulated free enterprise.

The adoption of a market based exchange rate, which would attract inflows of private capital and foreign exchange, is the only way to remove the expanding gap between the official and parallel market exchange rates. Many developing countries have tried and failed to maintain a fixed exchange rate. African countries that still have fixed exchange rates are: Cape Verde, Comoros, Eritrea, Lesotho, Namibia, São Tomé and Príncipe, South Sudan, and Swaziland.

Such draconian and coercive undertaking of major currency exchange exercise–remember, if every Nakfa is surrendered, that is 62.4 billion of it being counted, exchanged, documented, witnessed, audited– would have been unnecessary as the underlying issues would have been addressed by the institution found in an open, politically stable, democratic society that aims at maintaining an independent central bank that benefits the economy and not the intelligence entities.

People are overwhelmed by the corrupt environment that the regime created, they are trying to make a living, and now they will be impoverished or arrested. Even the ardent regime supporters who often use the black market when vacationing in Eritrea will find a way to circumvent the rules as they will not be happy to be required to exchange their money at a fraction of the black market rate.

As a result, the Eritrean Nakfa has become as good as a USA penny (down from 12 cents in 1998); its purchasing power is eroded, and such a situation doesn’t encourage investing or doing business. The decision to change the currency in such a haphazard way will result in a higher inflation, higher exchange rate and more corruption that will kill the already damaged economy.

In short, with all powers concentrated under one man, Eritrea does not have institutions that can ensure macroeconomic stability, control inflation, exchange rate stability, attracting foreign investment and supporting economic growth. Unless the government embraces institutionalism, accountability, transparency, the only way it will get people to do what it wants them to do is through its coercive powers. And that, as every failed communist nation has demonstrated, is no way to grow and develop.

Awate Forum