Eritrea: Gliding With Broken Wings

The following article by the Sudanese journalist, novelist and writer, Rania Mamoun, appeared on the October, 2015 edition of the Qatari Arabic Magazine, Al-Dowha. The magazine is an exceptional informative magazine and we encourage you to visit it. Rania’s article entitled, إريـتـريـا..التَّحليق بأجنحة مكسورة “Eritrea.. Gliding with a broken wing” is translated by awate.com. On behalf of our readers, we are grateful and we thank Al-Dawha magazine for covering Eritrea and we hope it will continue to do so in the future. We also thank the brave Sudanese journalist Rania Mamoun for the great journalistic work reported in a humane and artistic manner.

We have tried to make the English translation close to the original Arabic as much as possible, however, we admit, most of the beauty of the Arabic prose is lost in the translation.

Eritrea, a homeland of passion and beauty, with picturesque nature, the land of exhilaration and warmth, yet, this country is suffocating its children, mostly the youth who dream of escaping from it.

My friend and I carried our bags; we had received many advises and warnings, importantly, and first and foremost: beware of talking about politics! The warning had raised my curiosity, I felt the advice stems from an exaggerated sense of security, if not out of a wild imagination.

We crossed the border on foot–from the city of Kassala in eastern Sudan to the first crossing point in the Eritrean territory, and we went to the office to secure an entry permit. I observed the place while we waited for the completion of the permit process: modest crossing post like the one in Kassala, a lounge with some tables and a lot of border crossing permit papers, and staff with depleted patience. Outside, a large courtyard fenced with straws and straw mats, including a shade made of straws, and several buses to transport passengers to Teseney. I didn’t feel I was in another country, the features of the faces were the same, as well as the dresses, even the language was Arabic, except for some Tigrinya words that my ears picked from time to time.

On the way to Teseney I saw the nomadic life, and the poverty in the villages that we passed through: simple, small houses, many of them inside courtyards fenced with corrugated metal sheets or straw fences–children, goats, and pack animals. Wars have exhausted this country, and its people.

We stayed at a resting place facing the transportation station, a mere, wide, fenced yard with some trees, hosting tens of families. Tens of women chatted while waiting for the arrival of the next day to travel to their respective destinations. Since I entered the place, accompanied by Meyas, we became their show, they begun to follow all our movements, our conversation, and our many questions to the workers in the place, as curiously as someone in need of a pastime. We didn’t want to stay overnight in Teseney, and we were delayed trying to find a bus that would take us to Keren—a town about four hours drive away. We rented a private car owned by a humorous person with witty comments. He spoke Arabic fluently, and memorizes many Sudanese songs, a great admirer of Zinedine Zidane the football player, so much so that he gave the full name to his son. He said that women are so flexible that they can be bent without breaking; he did not hesitate to squeeze four of us (two women and two men), in a seat that is meant for three people. He was able to absorb our anger with the beauty of his spirit.

Assailing us with his talks, he said he was happy for the serious injury on his leg which he was inflicted with in the course of performing compulsory national service. It required the care of Italian doctors who attended to him for several months. However, he was thankful for his leg injury, because of which he was free. These words stuck in my mind, and it will be part of my enquiries during my journey in Eritrea; the foremost concern and the motive of my journey was the Eritrean person. The beauty of the place is important, but it is the human being who gives anyplace its soul and its individual emotions.

***

The road to Keren via Barentu, and Agordat, and others, is mountainous, like most snaking roads, towering in high altitudes and linking the Eritrean cities. And it is very dangerous: on one side there is a deep escarpment, on the other, an ancient mountain. However, despite its gravity, it is covered and adorned with beauty: it’s graced by a blanket of lush greenery, beauty and magnificence, mountain goats and monkeys that continuously emerge from nowhere, and spread over hundreds of meters on the edge of the road, and the mountain, killing boredom with the spectacular scenery of passing cars and their passengers.

Martyrs’ graves are distributed on the outskirts of the cities where it’s possible for the travelers to see them, as if a hand spread to welcome and shake the hands of those entering the city, or a hand gesturing to them upon leaving—graves that do not care about the religion of the martyr, embracing both Muslims and Christians; everyone is the same in sacrifice. I felt the high regard with which Eritreans hold the martyrs of the revolution which was launched in September, 1961, to achieve independence.

Keren, the beautiful city, is a quiet organized place, nestled in the bosom of the hills, whose major inhabitants are the Blin people. The city has relatively low residential buildings, that are well taken care of, its paved streets are clean, it has abundant greenery and is embraced by the sun with a special form of rays that are in harmony with the overwhelming white coated city—Keren looked like a piece of a smooth and transparent cloud.

In order to reserve rooms in the hotel, first we had to go to the police station and register ourselves! This procedure surprised us very much, but, it is imperative that we do what we should, and we thought: This is one of the manifestations of a police state.

In the morning we went to the “Mewefar”, the transportation station, where the buses heading to Asmara and other cities gather. In a wide courtyard lined on either side by shops that sell snacks, water, soda, we found a “riga” [que], or a row, to reserve a place for each of us in order to board to the low-cost government bus. The que was a line of stones, empty water bottles, soda bottles, old shoes, bags, cigarette packs, plastic bags stabilized by weight stones—you can put anything available under your feet in the line to reserve a place. The line becomes long, at times straight, and sometimes it meanders, but, despite the chaos, each one remembers his place, though I do not know how they remember which one is theirs among the similar things; you may find three bottles of water of the same color, behind each other: whose turn is first and whose is next?!

However, the problem was not in the que but in that strange man, or governor of the “Mewefar” as we called him, who whimsically lined up the people, and allowed them to board for travel in the same manner; he yells at all, calls whomever he wants, and fills the bus with them, then changes his mind and orders them to get off the bus, and lines them up once more, and suddenly he declares: no one will board the bus—repeating such act more than once. Actually he was in control of everyone, taking them from one place to another; the travelers follow him around, he talks to them, rather, he yells at them, and they talk to him, and we do not understand what they were saying, or what was happening!

He carried a pen, marking their hands with it, and instructs them to remain in a specific place. He is a short man, shaggy hair, sharp features, anxious movement, walks in quick steps, in confusion, he acted in an exaggerated oppressive manner as if taking out his rage on them.

We were moving back and forth to the station, under the hot sun, and scarce shade, and time was running on us, we stayed for nearly two hours in a hopeless situation, to no avail. Finally, we cursed the government buses and the mad employee, and we decided to rent a private vehicle to take us to Asmara.

***

Asmara is charming city, its beauty is breathtaking, rising to 2300 [meters] above sea level, unique in its European style architecture, Italian marks, African mood, and its beautiful Eritrean features, the people dress in European costume, and others in traditional attire, which is overwhelmed by White colors.

It is difficult for one not to fall in love with Asmara, the city whose mornings are saturated with dew, carrying the smell of coffee and tenderness of mothers, the city of prayer calls and bells, mosques and churches, steadfastness and challenges, patience and oppression, poverty and riches. Asmara, the calm witness to blessed love stories, of lovers, and gestures with hints.

We did not feel alienated in the middle of the black faces. The place and its features has changed, but the friendliness overflowing from the eyes made us feel the welcome. The Eritrean people are friendly, kind, refined, and hospitable. Samson (or is it Samir) whom we met at a restaurant insisted that we share his food, he was also not thrifty in sharing with us the details of his life. He, just like the city, embodies the differences. His ancestors came from Mecca 700 years ago as Muslims, and part of their grandchildren remained that way, while Samson, or Samir, the Eritrean Arab, who carries two names, is a Muslim and a Christian at the same time—something that prompted question from all of us.

One of the rituals of visiting Asmara is the promenade, even for one time, in Campo Citato, or the Liberty Street, the heart of the city whose streets are lined with palm trees, and on its sides, shops, government buildings, restaurants and cafes. Many hotels overlooking the street surrounded it for the convenience of tourists, since the street is a place of major attraction.

In that street is the Asmara Cathedral, or St. Joseph (1922). An everlasting and magnificent architectural icon, in the middle of the leisurely street and its attached buildings. At the entrance of the Cathedral is a platform that is reached through a flight of stairs that start from the sidewalk. But the stairs are not used to be scaled or just for landing at the platform. Sitting on one of the steps is fun, and hope. There, one follows, visually, the cars, and watches the surrounding buildings, and the banners on the buildings written in Tigrinya or Arabic, or English. One may have a packet full of freshly roasted peanuts, or a water bottle that one slowly drinks from, observing the passers-by who choke the street, as they come and go, in different attires, ranging from the traditional to the modern, and of different ages though overwhelmingly young.

That platform is a waiting place for a friend or a lover, it is a place for invigorating the lungs, and conscience, a place for reflection and contemplation, watching Eritreans patiently waiting for the coming of a transportation vehicle, where the bus is filled and overflows. I followed the steps of an elderly woman in a traditional dress, a wide white dress, and “netsela”, white cotton fabric with embroidered colored edges, predominantly in red, carrying things that she spread on the ground, and in a few minutes she sat down on a small stone, and displayed her wares in front of her: cigarettes, tissue paper, and nuts. Close by, a young girl, with whom we established a silent friendly connection and exchanged smiles every time I glanced at her in a place, near Cafe Diana, also exhibited items on the ground: sunglasses of different colors and shapes.

Not far from Campo Citato street and the cathedral, there stands the Khulaf’a Al Rashideen Mosque, which accommodates ten thousand worshipers, and which was built in 1900, and renovated in 1936, and is one of the most prominent landmarks of Asmara for its quality of construction and the splendor of its design and its religious status.

In Campo Citato Street, the cafes are full of patrons, especially on holidays, and it would be difficult to find a table, or even a chair from the seats and tables spread in the open air, or inside the café. If you find one, that must be a rare occasion, and you are surrounded by the sounds and laughter, different scents, and you feel elated if a Tigrinya word knocks at your ears and you happen to know the meaning of the word–and familiarity increases.

Intriguing advertising signs on the wall along the opposite side of the street invoked my surprise. They were not announcements of public concerts, or movies showing in cinemas, or art galleries, but displayed announcements of social events, of marriage and death. The announcements of death may also be accompanied by an image of the deceased. Probably it is due to the difficulty of communication between the people; there is only a single communication company operating, and it is government-owned. In addition, there are controls for owning a mobile phone card—which is not allowed except for a certain category of people!

One day, while sitting in front of the cathedral, I saw Hassan who got off his bicycle and came towards me. It occurred to me that Eritreans like riding bicycles a lot. It’s the forty-years old Hassen, our Eritrean friend who collected all his dreams and hang them on a rope of hope with a single peg: to be a trucker on the Khartoum-Port Sudan highway after he leaves Eritrea. Hassan loves driving, most of his talks are about that and about cars, and his memories are of the time when he was a truck driver in Sudan, and between Ethiopia and Eritrea. He memorizes the distances between all of the Eritrean cities, in kilometers. He awaits the day he would be able to leave the country and reach Khartoum, without falling into the hands of the human trafficking gangs.

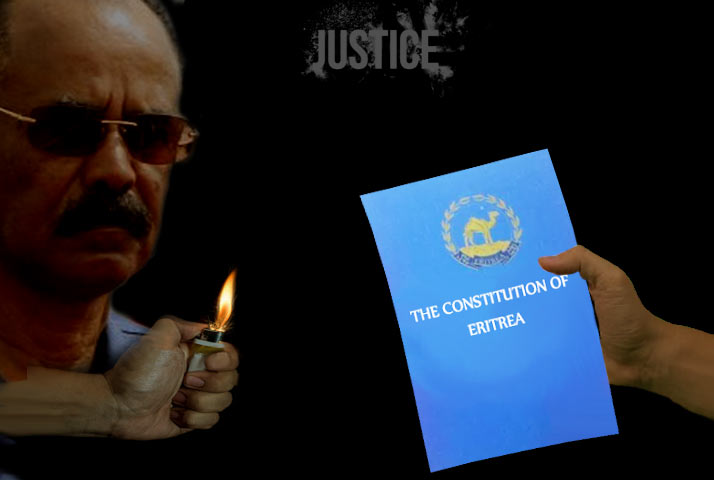

Eritrean youth suffer from a harsh and impossible situation that results in human tragedies, in the seas and deserts and the borders, under which Eritrean refugees and migrants live. The youth are unable to leave the country legally, unless they are released or they complete their indefinite compulsory national service. The youth may spend more than half of their lives in the service (either military or civilian), and that stretches for years, it increases but doesn’t decrease, though in many countries, the period of compulsory service ranges between 12 and 36 months, as a maximum.

I asked Feven (a nice girl) who would later invite us to her home, about the period she spent so far in the service. She said, after checking to the left and right over her shoulder: 3 years. And when will you be released? She replied in sadness: I do not know… No one knows.

Then I also glanced to my sides, Meyas did the same, and Hassen was continuously glancing; everyone here glances to the left and to the right when anything concerning the government is mentioned, no matter how insignificant. Is the sense of insecurity prevalent in our homelands to this extent?

In her simple and intimate home, we met her mother, Akhberet, who was, together with her husband, a combatant in the liberation struggle—there is a picture of them sitting on an elevated ground, smiling brightly with hope, young and beautiful, with guns close by. She told us about her years in the struggle during the coffee ceremony, inside the room, made carefully and with special rituals of love. We sipped the coffee, and after each sip, we said, “Teoum Bun”. Later on, in the same room, we ate a very delicious food called Hilbet, which is made of on injera (bread), a mixture of yogurt, some marinating ingredients, and stew full of hot spices.

***

In a permanent exhibition in Asmara, we met two young artists: Semander Yosief, and Abel Gebrai; they were exhibiting their paintings, paintings that centered around the life of the Eritrean person as their theme. The paintings of Semander were about the nine nationalities of Eritrea, portraits, or captured moments of life, about cultivation or grazing. While Abel’s paintings focused on the sensations and emotions, as a portrait of a man looking far ahead, stretched lips, and with clear determination, or a girl gathering her dress around her body, an obvious pain on her face, as if trying to shelter herself from the brunt of the severe pain she felt.

Despite the beauty of all the paintings, one that had most effect on me was the one with two intermingled bodies, two bodies of lovers, friends, brothers, sisters, or a mother hugging her son after his survival and return from a shipwreck, kidnapping, or death. Abel named the painting, “REUNION”.

He said: We are suffering from fragmentation and separation due to the constant escape; so, I painted this painting.

Abel coined the longings and dreams of Eritrean to meet those they who parted, those who went far away, when the chances of their survival is negligible compared to the inevitability of their demise, but nevertheless they leave! Eritrean youth escape towards death while escaping from what’s worse: a miserable life.

***

Three women came in: two were above fifty-year-old, wearing traditional dress, a white dress and large white scarves; the third was a young girl in her twenties, wearing black pants and a blue blouse. They entered the night club shyly, and hesitantly; one of the women covered part of her face with her scarf, and the second carried a picture of a young man in his early twenties. Under the picture was a text of some Tigrinya phrases, and the young girls carried an open bag, inside it were some Nakfa bills.

Shortly after they entered, the music stopped, and something was said over the loudspeaker, and then came the waitress to help them talk with people around the tables, even though the event does not need talking.

The women’s faces wore excess of grief, pain, and modesty, and they looked anxious. They were moving, the three of them, slowly and silently, from one table to another, to collect donations. They were carrying the photograph of the kidnapped son of one of the women and the brother of the girl; his kidnappers had demanded a ransom that the parents, the family and the whole village were unable to collect: thousands of dollars.

I did not dare look in the mother’s eye when they arrived at our table, who dares to look in the eye of a grieving mother?! I felt ashamed, complete helplessness and sadness engulfed me, I trembled from the pain, I felt like an excited blade was cutting through my heart, and the malevolent blade stuffing pepper in the wounds, and then smile.

In rage I wanted to cry, that’s what Hassen did in Massawa, after we watched a documentary film about the tragedy of the Eritrean refugees; if they succeed in crossing the Eritrean border, there awaits them kidnapping gangs, or they are deported, or they are held for a ransom, or they are sold, or their body parts are extracted and they are left to bleed to death in the desert, or they are shot, or are swallowed by sharks in the sea.

Hassan, still crying, said: he did not want his kidneys to be stolen, or to die in that manner. Nevertheless, he wants to escape.

***

When we were walking around Massawa, I felt I was wandering in a history book, between its yellow pages where time left its footsteps: in the buildings, and in the homes, especially in old-Massawa, and in the streets; so did the war. Effects of all of that manifested in what I saw and sensed of the city, and my modest knowledge about it, though it has remained in my memory since the school days, as the city that opened its arms for Islam and the religious migrants who were seeking security in it.

In old-Massawa there is the Sahaba Mosque, whitewashed, with windows and a small wooden gate. Part of the courtyard is fenced with corrugated metal sheets, and consists of two buildings, above one is a minaret, and between them a courtyard. At first, I thought the mosque was built after the migration of some of the companions to Massawa, but now I am uncertain.

There are also crumbling stone houses, with rickety wooden doors, or rusty metal sheets, I thought of them as abandoned houses until I saw a child of about 3 years, standing on one of the doors.

At the other side of the city, at a modern style entrance, three tanks snatched by the rebels majestically stands on a dark marble base, including the first tanks that was seized in August, 1978, in the area of Addomzemat, south of Asmara.

On the way to Massawa, the ability of human determination expresses itself in taming nature; a road cuts through the mountains, rippling through it as ornaments on the edges of a leisurely walking bride’s dress, a road that gets you closer to the sky, hovering in the clouds, you throw away your worries, and be immersed in the pleasure of viewing. Watching the mountains, trees and villages scattered at that height, reaching to the roofs, a virgin life, in balance with nature, coexisting in harmony. We saw the shepherds behind their herds, women, carrying firewood on their heads and thinking of what to cook for their children that day, and children curiously standing to watch the cars, smiling, waving, while wearing that plastic shoe named “Shidda” of which we saw a monument in the Shidda Square in Asmara, which was built to commemorate it, because the rebels wore that shoe during the years of the revolution, from 1961 to 1991.

The beauty of the road and its greenery inspired an appetite for dreaming within us, each one of us followed their dreams, without the fear of the precipitating rain, or the fog that blocked our vision and compounded the risk of the road and its many narrow bends, and limited our vision to less than a meter. But the car continued ahead through the dangers, without worrying about the possibility of an imminent death, we continued in our dreams, in our aspirations and memories, and our feelings flowed, and we thought about loved ones, and inside the heart sat a concealed melancholy, about the person of a country named Eritrea, who began his journey towards it with curiosity and passion, and finished it with love. But the heart that went there is not the same as the heart that returned.

Awate Forum