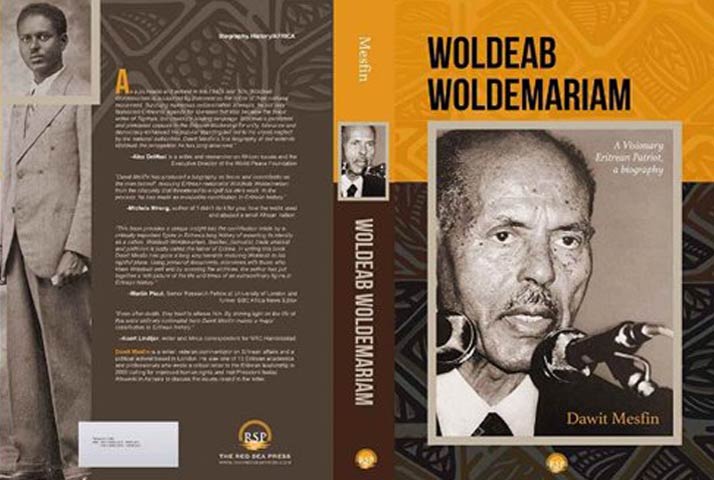

A Thorny Path: the Life of Woldeab Woldemariam, Eritrea’s Campaigning Visionary

There were very few actively engaged citizens who withstood the test of time and lived through Eritrea’s past struggles. One of them was an elder by the name of Woldeab Woldemariam who passed away on 15 May, 1995. This is his story.

In 1997, when Mrs Hillary Clinton began her nine-hour visit of Eritrea, the first thing she did was to acknowledge Eritrea’s martyrs in the independence struggle by laying a wreath near the grave of the great patriot Woldeab Woldemariam.

Woldeab embarked on a project that trailed a blaze in Eritrea’s nationalist movement. His contribution influenced many Eritreans to choose self-government (40s), challenge the ill-fated federal agreement with Ethiopia (50s) and rise up against the annexation of Eritrea by Ethiopia (60s), which led to the launching of a fierce and costly armed insurgency that lasted for three decades.

Unfortunately, most of Woldeab’s history, in spite of his popularity and wide ranging contributions, died with him. Apart from some trivial accounts that appeared on various newspapers and Internet articles, his overwhelming involvement in the construction of Eritrean nationalist struggle has not received the attention it deserves yet. I suspected something was wrong. Years of research proved that my suspicion was substantiated. The outcome is included in this account.

Denying Eritreans a solid grounding in the history of their former heroes is deemed to produce a generation of uninformed citizens who will be swayed by those who happen to ‘own the country’s history’. Actually, that is what is happening in Eritrea now. Therefore, to follow Woldeab’s life journey becomes necessary because it will enable historians in particular and the public in general, to face up to the triumphalist and exclusionist version of history that has been imposed by those in power.

Woldeab, before he went into exile in 1953, excelled in teaching, writing, journalism, activism and trade unionism. His language skills, for a man of his era, were quite remarkable. He spoke and wrote Italian very fluently, and used Amharic, the leading Ethiopian language, Swedish and English in his work. His writing style was so exceptional that many refer to him as the father of modern Tigrinya (one of Eritrean languages). Moreover, he was guided by a unique sense of morality, one that was principally based on his Christian faith. Many remember him for his radio broadcast from Egypt which inspired many youngsters to follow his footsteps. But most of all, Woldeab remained one of the prominent nationalists who tirelessly campaigned for Eritrean independence for almost five decades.

During his Eritrea-for-Eritreans campaigns Woldeab became the target of the irredentist groups who perpetrated seven assassination attempts on his life. He was fiercely opposed by the Unionist Party and its unruly youth group, leaders of the Orthodox Church, many members of his own Protestant community, the Shifta (terrorist groups), as well as agents of the Ethiopian Government. In exile he lived a difficult life as members of the two pro-independence factions he was involved with were at each other’s throats. He witnessed the religious divide between the fighters grow larger. At times he was unfairly blamed for his old-fashioned, ‘crusader approach’ and unbending principles by the competing factions.

Eritrea’s independence came in the nick of time for the old patriot as he reached the end of his life. Perhaps that propped up his emotional state and mitigated the pains of old age. Most of his contemporaries had passed away by then and Eritrea was populated with people of his children’s and grandchildren’s age.

When Woldeab died his funeral attracted tens of thousands of mourners – the biggest gathering of mourners in the country’s history. The ceremony was a demonstration of gratitude for committing his entire life to fighting injustice and campaigning for the independence of Eritrea. Surprisingly, after his death, due to lack of recorded account of his accomplishments, his memory has fast faded.

Now I know why a monument has been erected for Alexander Pushkin, the renowned Russian poet, in the heart of Asmara, while the country’s most prominent pro-independence campaigner, one who co-fathered Eritrea alongside his fellow nationalists of the 1940s, is brushed aside. In point of fact, this account reveals how and why a hero such as Woldeab is systematically dismantled to make way for others to shine. Having uncovered some long held secrets about Woldeab’s views, reflected on the outcome of my ten year journey, now I am intensely curious as to what will happen to this hero’s reputation after this account is published.

This project is an attempt to capture faded memories of Woldeab. He is part of my history – the source of my identity and fledgling patriotism. I came across Woldeab’s name as a young boy in the early 1960s. I remember it was forbidden to mention his name in our household due to the menacing atmosphere that surrounded his reputation. The atmosphere around my first school where he taught students of my father’s generation was also the same. His name was totally effaced from the school environment where he presided over as school principal. The teachers knew him well but no one dared to mention he ever existed. Members of the Church community, located around the school, had totally disowned him. However, the older youngsters who knew more about him than us revered him. The younger generation, in total disapproval of their parents’ pro-unionist sentiments and position, formed underground circles that venerated Woldeab’s ideals. That enticed my interest in his persona. And that youth rebellion is what prompted the armed struggle for independence in 1961.

Woldeab’s journey affected Eritreans from all walks of life. The struggle, which lasted from 1961 to 1991, claimed the lives of an estimated 65,000 freedom fighters and tens of thousands of civilians. Victory created an utter feeling of elation which lasted for months as the returning freedom fighters reunited with their family members. Also Woldeab, who was old and feeble by then, returned from exile. He began to lead a quiet and secluded life in Asmara. Startlingly, it did not take long for Woldeab’s pre-independence prediction to materialise that independence would fail to bring liberty for the people of Eritrea. It did not take long for the freedom fighters to change their posture – their focus turned to power, their relationships with one another, and their norms and ethics.

The Audience

A comprehensive history of Woldeab has not been published yet. However, there exists a PhD thesis written by Dr Denise Saulesberry, an American academic whose focus of her research is Woldeab. There are other books on Eritrea who mention Woldeab’s life and his struggle. But they lack perceptive aspects of who he really was. The chapters in this book are a collection of the dramatic experiences that helped shape his destiny and that of his country. It is the story of an epic life which experienced hope, hardship, resilience and ultimate triumph.

Moreover, Woldeab is not in the history books of Eritrea except in Alemseghed Tesfai’s book which is written in Tigrinya. School books in the country barely mention his name and the struggle he and his compatriots conducted during 1941-1961. Considering that those early years of struggle changed the course of Eritrean history, the young generation grew up learning very little of who he was, what happened during the years when he was most active. This book will help them construct their own understanding of how Eritrean nationalism came about – a phenomenon mostly influenced the lives of their fathers and grandfathers.

The other target audience for this book will include historians, and Africa watchers, but also a broader segment of the public who are engaged in current events, politics, and international affairs.

The Book Structure

The book starts with an introduction which focuses on the eleven chapters of the book. And it gives the reader a flavour of how the book came about and other information the reader should be aware of. It describes the ups-and-downs of the journey, the sources, the fears and trepidation of Woldeab’s family members which obstructed the smooth development of the story.

Chapter 1: Now ‘I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings’

In this chapter the mystery surrounding the life of Woldeab whose story should tower over the history of the young nation of Eritrea, is unearthed through his quietly documented thoughts which I refer to as the Woldeab Papers. Now I can say I know why silence descended on his death. The account is based on information I obtained towards the end of my project in the form of a transcript of interviews Woldeab had given in 1987-1988 to a confidant. His comments, delivered in the measured, poetic tones typical of the man, delivered a damning verdict on the leadership of the EPLF, Eritrea’s revered freedom fighters who have taken the reins since independence (1991). The Woldeab Papers warned of the dangers of arrogance and personality cults within the EPLF. His reward was a concerted but quiet campaign during his later life, and even more so after his death, to air-brush him from Eritrea’s history.

Chapter 2: Woldeab and Family

The account focuses on the story of Woldemariam and Waga, Woldeab’s parents, which is an inspiring one. The illiterate individuals who left their homes in Tigray (Ethiopia) and travelled to Eritrea before it became Eritrea, contributed to the country’s wellbeing with their hard work and by giving it their high achieving children. The family’s contribution to Eritrea – to every aspect of its national life – was extraordinary and has to make it one of the most significant in the history of the country. Without the contribution of Woldeab, their visionary son, Eritrea would have assumed different political, social and economic contours. He greatly assisted in putting Eritrea on the world stage.

Chapter 3: Woldeab and the Contested Land

Unlike many other states in Africa, Eritrean nationhood came about via a succession of events, one of the most important of which was Italian colonialism (1890-1941). The British occupation (1941-1952), the ensuing Ethiopian intervention which paved the way for federal agreement and later resulted in the annexation of Eritrea, continued the shaping of Eritrean nationalism. The narrative hinges on how Woldeab lived through all the eras that defined Eritrean nationhood. Woldeab explains 1) how the Italians, using their political and moral might, destroyed Eritreans in the name of peace and security; 2) how the British tossed fire into Eritrea and between Eritreans in the name of liberty.

Chapter 4: The Teacher

The account in this chapter captures the essence of human transformation – how Woldeab’s life was transformed as he became a teacher. Woldeab used proudly to say, even in his old age, ‘I am a teacher’. As a teacher, although respected and admired, he was known for his conservative values – sometimes feared as a disciplinarian by his students. His formal education at the Swedish mission school in Asmara had been in Italian, giving him a window into a foreign life. Signe Berg, a Swedish missionary who had mentored Woldeab in his early days as a teacher in Kunama-land, always admired his earnestness and competence in the classroom. ‘Woldeab is such a confident and poised teacher’, she used to say. Woldeab taught literacy, the Bible, languages, music; and such was his hunger for learning that if he was not teaching others he would teach himself. Woldeab was so driven he used to spend days studying one of the classics of Western literature, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy and the richly romantic poetry of Giovanni Pascoli. In terms of what he taught, and how he made it accessible to the students, he was endowed with an aptitude which was ahead of his time.

Chapter 5: The Journalist

The theme of ‘The Journalist’ depicts the calamities freedom of press creates in a virgin territory. When the victorious British army marched into Asmara in 1941, the state of affairs went from bad to worse in the country. Although the Italians wanted to remain a considerable player in the future of the country because they felt they had ‘Italianised’ Eritrea, the prospect for Eritreans to remain ‘Italian’ was very slim. The British, meanwhile, did try to usher in change, but it only had the effect of creating instability in the country. They could not maintain order and revive the economy. The changes, such as freedom of the press, were not introduced methodically – without preparing and empowering the people. During that time the British hired Woldeab to run the Tigrinya version of the Eritrean Weekly News (EWN). Sadly, EWN opened a Pandora’s Box of domestic problems. Woldeab was immersed in the thick of a chaotic transition period. The newspaper project was meant to aid the British to introduce their values and entice the local population into falling in line with their vision of how Eritrea should be shaped. On the contrary, the debates put rivals on the warpath in defence of their respective ideals.

Chapter 6: The Wordsmith

Woldeab recognised how the use of language was related to the exercise of power in Eritrea and how he could use it to stimulate serious discussions via the Eritrean Weekly News. But it was not only Tigrinya that played a significant role in Eritrean politics; Arabic was the language used by many lowlanders to articulate their political thoughts. Likewise, Italian, the public language of the ruling and political elites, shaped the mind-sets of the Eritrean intelligentsia.

As the editor of EWN, Woldeab was in a key position to influence his readers. The period in which he could write publicly, deploying the power of his excellent Tigrinya, was one of the most significant episodes in his life. Did he write to solve Eritrea’s problems? Unlikely, but he certainly wrote to allow them to emerge. Woldeab had clearly understood that Tigrinya was the language of political debate, not only that of Eritrean freedom politics, but also of the mighty Unionists, his opponents, who were backed by Ethiopia.

Chapter 7: The Activist

‘The Activist’ chapter reconstructs the episodes of how Woldeab turned into a modern-day activist who ushered in new sense of national consciousness in the country. It shows how his ideals, that Eritrea would be better off if its people would demand, and ultimately fight for, their autonomous existence, began to resonate with the public. It also addresses how his own vision evolved to a point that it goaded others into developing their own ideas about Eritrea’s future.

Chapter 8: Woldeab and Banditry

This chapter focuses on a collection of unpleasant episodes that were hard to compile. It is a story of how Woldeab stood up not only to his enemies, but also his friends who betrayed him. As many influential Eritreans began to support the notion of Eritrea for Eritreans, Woldeab, dubbed a pathetic turncoat by the Unionists, became one of the primary targets of the Andinet (militant youth group) and Shifta. Eventually, his enemies, after committing seven assassination attempts on his life, did manage to intimidate, silence and drive out not only his fellow campaigners but Woldeab himself, changing the course of Eritrean history.

Chapter 9: The Trade Unionist

This chapter depicts the assaults on Woldeab on various fronts. He had to put up with not only the Shifta onslaught, denunciation by the Orthodox Church, his rejection by the Evangelical community, the distancing of family members, pressure from Ethiopia, the British/US support for Ethiopia, the UN federal verdict, he also had to cope with the splintering and uncoordinated work of the pro-independence group. He simply could not catch his breath. How could he give new life to his appeal to the people under such circumstances? Trade-unionism was the answer. The movement Woldeab launched was an answer to the triumph his critics and enemies relished over his group, pro-independence. Woldeab embarked on the trade union vehicle because it gave him the opportunity to redeem himself and help him make a political come-back. According to Woldeab, the hearts and minds of young Eritreans and factory workers were slowly changing, and this spurred him on. The syndicate of Free Eritrean Workers was becoming an increasingly powerful and respected organisation under his leadership. And then disaster struck. He was attacked and badly wounded by revolver shots in the main street of Asmara. Woldeab was not expected to survive the 7th attempt on his life, and indeed it took five months in hospital for him to recover. Soon after his recovery he went into exile.

Chapter 10: The Nationalist in Exile

Life in exile was a time of great mental anguish for Woldeab; he could not bring himself to acknowledge the dawning of the new reality – the fact that he was not the major player he once had been in his country’s destiny. After living in Khartoum for six months, Woldeab moved to Cairo to run his radio station. This chapter summarises his on and off struggle that lasted over two decades. Unfortunately, the belief of the Eritrean community in Cairo, all Muslims, was not in step with his religious humanism. They discriminated against him for he was a Christian; most of Eritrean Christians supported unity with Ethiopia. Anyway, his radio messages were effective. Back home people sat around the radio and listened to Woldeab’s messages on unity and how Eritrea should remain in the hands of Eritreans. In exile Woldeab witnessed the Birth of Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM), Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) and Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) – all factions experienced discords and war of attrition amongst them which broke his heart. However, although his role was diminished to observer-level in 70s and 80s, Woldeab remained hopeful that the fighters would come to their senses to liberate the country. Fratricidal Strife among Freedom Fighters became worse. During those tumultuous times he lived in seclusion in Cairo.

Chapter 11: The Revenant

This chapter is an account of Woldeab’s sunset years of his life as he triumphantly returned to a liberated Eritrea, where the ordinary people welcomed him with reverence. To them he was the symbol of the struggle for independence, a factor that drew the jealousy of the Young Turks who led the EPLF, the party of the country’s victorious freedom fighters.

As Woldeab slowly melted away into obscurity, privately he received visits from ex-fighters, admirers, journalists and family members but never from the president. According family members, President Isaias visited Woldeab only once, and that was when he was on his death bed. Nevertheless, Woldeab continued to entertain and advise his visitors until his death.

The final epilogue describes Woldeab, according to his opponents, as a man of ‘illegitimate heritage’ to lead a nationalist campaign. It also describes how Woldeab worked for Eritrean independence throughout his adult life while many segments of the Eritrean society worked against him. The old campaigner’s life was parcelled out in periods of adventure, intrigue, danger, conflicts, pointlessness and irrationality that nurtured eventual rationality. But one thing remained constant for Woldeab. He loved the Eritrean people and the people loved him back. In the end that is what counts in a life of a hero. What transpired after his death is a different story.

About the Autho

I am writer and commentator on Eritrean affairs. I am also an activist – I have participated in many projects and campaigns for democratic and human rights for Eritreans. I was one of the 13 Eritrean academics and professionals who wrote a critical letter to the Eritrean leadership in 2000 and travelled to Asmara to meet President Isaias Afwerki to discuss the issues raised in the letter. I used to regularly contribute to Eritrean websites and worked as a senior editor of Asmarino.com. I am a founding father of Awate.com, a prominent Eritrean Website/Foundation. I then set up and ran Voice of Liberty, a SW radio station transmitting from Europe to Eritrea. I chaired EHDR-UK (a London-based human rights group) and NECS-Europe (an umbrella organisation of 13 civil society organisations based in Europe). I have travelled to Sweden, Holland, Switzerland, Germany and the US to give presentations on various subjects regarding Eritrea. I worked for London Metropolitan University, International IDEA, and I was the principal director of Justice Africa, an international NGO, from 2011-2014.

Awate Forum