The Emperor’s Daughter and her Namesakes

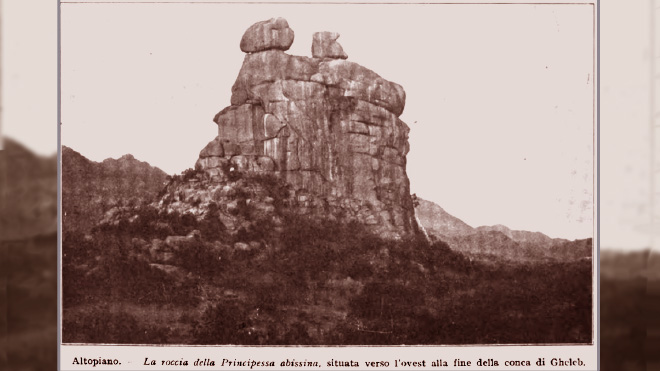

ወለት ሓጸይ, ጓል ሃጸይ, the emperor’s daughter, la fille du Negus, la figlia del Re, la figlia dell’Imperatore or la Principessa are names coined by the locals and foreigners to the legendary figure located in the middle of the Gheleb basin (Eritrea). She fascinated the poetic people of Mensa’e (መንሳዕ) and attracted the curiosity of visitors to the area like Denis de Rivoyre, Ferdinando Martini, Karl Gustav Roden, Capitano Hidalgo etc. My search right and left to know her identity brought me across other emperor’s daughters revealing she is not the only one with the ‘ጓል ሃጸይ’ designation. Two namesakes were found, perhaps not as famous as, but worth mentioning what we know of them. One is the elusive daughter of king Fasiledes only known by that epithet, and the other a statuesque massif rock with the same name (ጓል ሃጸይ) located near Feres-Mai south of Enticho in Tigray.

One of the namesakes, the daughter of king Fasiledes (ጓል ሃጸይ) was the unfortunate bride given by her father to the then scabious nonetheless chevalresque Hab-Sellus, later dejazmach, forefather of a dynasty that ruled Mereb Mlash untill the tumultous time that ended with the advent of the Italians and the delineation of Eritrea. Fasiledes gave his daughter in marriage to Hab-Sellus in admiration of his exceptional bravura for breaking an untouchable horse, his equestrians couldn’t muster thus-far, and for his fidelity in doing things as per the king’s instructions. Unfortunately, the poor emperor’s daughter never placed her father’s hero in her heart. Midway on their journee to Hab-Sellus’s homeland, he approached her, but she refused to share with him her warmth. In an anger, he slapped her, resulting in her fall and unfortunate death. That is all we know about this poor emperor’s daughter, a daughter of the famous Alem Seghed (Fasiledeses’ coronation name). No name, not even a mention of her existence in the annals and history of her father. Nevertheless, she was kept in the oral history and memory of the Mereb Mlash people and later well documented by the relentless Johannes Kolmodin.1

The other namesake ጓል ሃጸይ of Tigray is an impressively standing massif rock, in the middle of a chain of mountains that surround the larger Feres-Mai area. The first colonial governor of Eritrea, Ferdinando Martini was fascinated to find a namesake for Gheleb’s ጓል ሃጸይ, south of his territory.2 He questioned a possible link between the two without elaborating. That is all we (at least I) know about Feres-Mai’s emperor’s daughter. Hopefully, someone will come with stories. Nevertheless, let me add my wishful thinking on the possibility that Hab-Selluses’ slap that ended the life of the princess happened in that area and some local indulgent personality coined the name to the massif in her commemoration! It wouldn’t be too good to be true if it was true! In an unprecedented way, following the death of the princess, Hab-Sellus had gone directly back to Gondar volunteering his neck by handling his own sword to Fasiledes in justice for what he did. After interrogating the princesses’ servant and learning the death was just an accident brought by his daughter’s refusal to receive her husband, Fasiledes pardoned Hab-Sellus only demoting him from his Abieto (ኣቤቶ) title to dejazmach and reducing his governorship from the earlier promise of Bambolo-Mlash to Mereb-Mlash.

The legendary emperor’s princess (ጓል ሃጸይ) of Gheleb:

It was while reading Denis de Rivoyre book on his travels to the Bogos, Keren and Sudan that I came across the legend.3 Gheleb is a town and an area found in a natural basin traversed by rivers and surrounded almost 360° by chain of mountains. Gheleb means shield in Tigrait or Tigré and truly it is shielded by those mountains. Amid the basin, not far from Gheleb town stands the princess with her Prince, frozen in time and surrounded by what were her peasants and their produces.

Mutual curses brought us this fortuitous legend. The most common straight forward story goes as follows.4 It all started when a daughter of a king, a princess, and her prince came accompanied by many followers to Gheleb from Abyssinia. Arriving there, the princess established herself with her prince. Her followers didn’t stay long. They opted to go back to where they came from, leaving her and her husband with the local peasants, who adopted her as their princess. The land was rich and made the princess prosperous. But with time she went mean & miser on the peasants. Despite the land providing sacks of wheat, teff, barley and other cereals at every harvest, the only thing the princess was willing to provide her peasants for food, day and night, was a bran polenta (ግዓት ንፋይ ኣኽሊ). The peasants became increasingly unhappy. One day they gathered and cursed her, her husband and her sacks of grain, all to be turned into stones. That put the princess more in anger, and in return she cursed the peasants to be transformed into red-buttocked monkeys. The Almighty allowed the mutual curses to happen. She and her prince turned into the standing rocks still seen side by side, glued tightly with their distinct heads, as massive statues in the middle of the Gheleb basin, becoming its landmark. The sacks of grain turned into the various sizes of rocks populating the base of the statue. The peasant turned into baboons still inhabit the area since generations. They enjoy climbing upon and taking their revenge on the once so powerful but mean princess and her prince.

There are variations to the story, but the above translated and adopted from Ferdinando Martini’s recollection is the most common.4 A shorter and slightly altered version was told by Capitano Hidalgo in his ‘Escursione nei Mensa’.5 The princess unlike her father, never wanted to give alms to the poor. Allah changed her to stone in punishment”.

It was Denis de Rivoyre who took the story to another level allegedly claiming it was told to him by one of his guides. The story is intricately long, told on 18 pages, that I will try to summarize the essential in a paragraph. King Lalibela had a beautiful and proud daughter named Judith. He had also a well-known baron named Neakuto Le’ab sent to Yemen on an expedition during which he established a good friendship with many Arab princes including Egyptians. When Neakuto Le’ab was recalled to his country, he was dwelt with a secrete ambitions, one for the crown and another for the beautiful Lalibela’s daughter, who subsequently resisted and repulsed all his advances. Lalibela had a monumental ambition to control and divert the Nile bringing Moslem Egypt to submission. To do so one day convoked all the notables of his country into a meeting and a feast near lake Tana. At the end of the speeches, Neakuto Le’ab stood to give a toast and handled a goblet to Lalibela. Following the first sip, Lalibela fell bleeding to death. Neakuto Le’ab immediately reclaimed the throne. Judith hearing the death of her father escaped through a back door and run to the north where her father had a trusted friend in Hazega. Unfortunately, this lord was not willing to hide her for fear of Neakuto Le’ab retribution, whose soldiers were chasing the princess. She continued running to the Mensa’e region. Arriving exhausted at a place (Gheleb basin), she implored heavens saying “O Lord save me! May your pity descend on the daughter of Lalibela!”. And heavenly mercy fell upon her. Her body stiffened and became motionless; taking the rigidity of stone; and in the place of this slender and graceful young girl, the gaze transformed into a compact mass, a block of rock, the reliefs of which continue to keep the outline of the folds of her garment.

Evidently, there are several untrue events in this last story that has no backing. None of the events are known to have taken place and the king is not known to have a daughter with that name. the interest of this story is just in the different version of Gheleb’s rocky princesses’ legend and on how the rock came to exist. The illustrious Rene Basset orientalist and egyptologist has reviewed Rivoyre’s book in details and regarding this specific story, he said was apocryphal.6 Similarly, Jules Perruchon another scholar on Ethiopia who translated several chronicles from geez including the life of Lalibela confirms the baseless nature of the events.7

Nevertheless, there are a lot of things to unpack in the last version of the story, which is based on personalities of history with the conspiratorial ideas behind and in the history and legend told above that I leave for the reader to contemplate.

References

1 – Kolmodin, J., 1912. Traditions de Tsazzega et Hazzega (Vol. 5).

2 – Martini, F., 1947. Il diario eritreo (Vol. 3).

3 – De Rivoyre, D., 1885. Aux pays du Soudan: Bogos, Mensah, Souakim. E. Plon.

4 – Martini, F., 1896. Nell’Affrica italiana: impressioni e ricordi.

5 – Hidalgo L. Escursione nei Mensa, diario del cap.L. Hidalgo. In Bollettino della societta geographica Italliana. Vol 3 – 7. 1894.

6 – Rene Basset. Livre nouveau Au pays du Soudan , Bogos, Mensah, Soukim. In bulletin de correspondence Africaine Vol 3 1885.

7 – Perruchon, J., 1892. Vie de Lalibala, roi d’Êthiopie: texte éthiopien publié d’après in manuscrit du Musée britannique et traduction française avec un résumé de l’histoire des Zagüés et la description des églises monolithes de Lalibala (Vol. 10). E. Leroux.

8 – Rodén, K.G., 1913. Le tribù dei Mensa: storia, legge e costumi… Evangeliska forterlands-stiftelsens förlags-expedition (Italian translation). Source of the image.

Awate Forum