Paulos Natnael’s “The Fighter’s Letter”: A Book Review

Book Title: The Fighter’s Letter

Author: Paulos Natnael

Publisher: Red Sea Press & African World Press

ISBN: 978-1-56902-410-2 (HB), 978-1-56902-411-9 (PB)

Pages: 289

The Fighter’s Letter will mark Paulos Natnael’s debut as a serious writer with a knack for story-telling. For over two decades, Paulos has written countless articles on Eritrean politics, but The Fighter’s Letter is like nothing we have seen before. The book artfully combines the familiar Paulosesque no-none-sense and no-beating-around-the bush approach with the mastery of story-telling where the aroma of awel bun (first coffee) pervades the ambiance throughout the ritual; and it is Bereka time (the last coffee) before you know it. The Fighter’s Letter serves an authentic and much needed Ethio-Eritrean coffee from someone who, as a young man in his last teen years, was part of the conflict as a volunteer freedom fighter.

Coffee-making is like writing; it is an art. It is the mark of genius for any writer who succeeds in making the familiar new and the new familiar. I knew most of the characters, the landscape, and the events, but the familiarity is such an integral part of the narration that I remained engaged throughout the bonfire of ideas, characters, conflicts and events; had to defy nature and stay glued to my seat. I have had the privilege of reading great and engaging books over the years, but The Fighter’s Letter was my story, an Eritrean story, an Ethiopian story, and above all, a human story; I was emotionally and intellectually lost in it. The beauty of this kind of literature is that it helps us immerse ourselves in ourselves and rediscover those important and transformative powers of empathy and sympathy. It is compassion that gives impetus to understanding and any judgment devoid of it will be hollow of justice, fairness and harmony. The politics of truth, reconciliation and normalization of relations with us and our neighbors will require a lot of empathy and understanding, and the few books that are being published, by both Eritreans and Ethiopians, should pave the way. The Fighter’s Letter has done its part.

The ultimate goal of The Fighter’s Letter is to enhance our understanding of the recent past while still maintaining the integrity of the truth. For example, the late Melake Tekle is portrayed throughout the book as a selfless fighter and bono fide hero who put the interest of others and the nation above himself; but it was also him, in 1975, who, as a privileged leader, had let more qualified Sudanese doctors attend to him while the rest of the ELF fighters were being treated by “barefoot doctors who served as medics in the military units but has no formal medical training.”

In an edifying moment, the book shows that there are no sinners without a future and no saints without a past. People rising beyond their inherent fallibility, follies, flaws and weaknesses is the source of their greatness. The great Melake came at a crossroad and chose sacrifice; and his story is being told to the young generation by people like Paulos Natnael who fought alongside him. There were few sinners who had squandered the future and left without redeeming their names, and the late Abdella Idris, according to The Fighter’s Letter, was the most notorious of all.

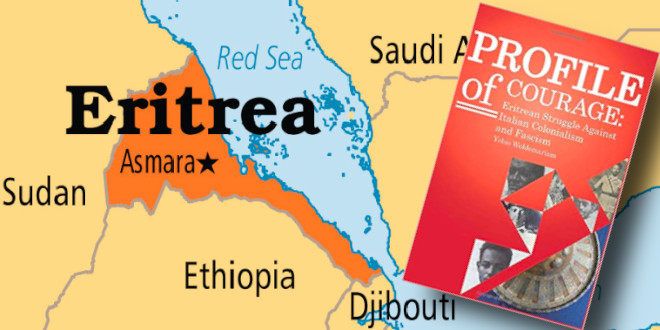

The Fighter’s Letter is a historical novel with a tall order of describing the “chaotic Ethio-Eritrean social and political landscape from the mid 1970s.” For majority of Ethiopians and Eritreans the period is so close and personal that one doubts if any writer would succeed in this endeavor; but Paulos Natnael has achieved a reasonable success. I knew Paulos through his writings in the good-old-days of Dehai and have always appreciated his propensity of not mincing words or twisting the truth to cater to audience’s sensibilities. He has always stricken me as a fair-minded individual with a strong penchant for telling the truth. It was with this expectation that I embarked on reading his book; I knew he would offer a compelling story that will enhance our understanding of the last four decades, or, at least, offer us an interesting perspective that will surely provoke us to engage in a serious discourse on a part of our history that is still a big part of us.

The Fighter’s Letter is a story of a family, nation, and region told from the perspective of a family that experienced the lofty aspirations and hopes of the revolution and its impressive successes and dismal failures. The impact of the revolution is felt in every aspect of the family’s life even among those who were thousands of miles away from home. The fighter’s family, Daniel’s family, is a modern Asmera family from the protestant enclave of Geza-Kenisha with a deep sense of its history and identity. The family traces its pedigree to the heart of Hamasien, the seat of the Deqi Teshm Dynasty, who were the traditional rulers of Mereb Mlash with blood ties beyond it.

Ironically, this duality mirrors the seemingly irreconcilable conservatism of the past and the openness of modernity that characterized the Eritrean revolution.

Modern Asmera, the birth place of Eritrean national consciousness, became the city where “Eritrean youths listened to Pop, R&B, Country, and Rock & Roll music that blared twenty-four hours a day from Kagnew. They dressed in bell-bottom trousers, half-unbuttoned shirts, and sported the new hair fashion: Afro. They watched Hollywood and Italian movies in the theaters and on television, although not many had access to the later. Cafes and teashops were always full of high school kids with that sort of Western influence. The traditional Eritrean way of life, the hard life of the farmer was rejected as backward. People from the rural areas were ridiculed and shunned by the young. The young didn’t want to associate with anything rural.”

And yet the revolution was fought in the name of cultural and linguistic identity; and it was these young people who were among the 64,000 Eritreans who paid the ultimate price. It is in these seemingly contradictory ideas where the author shows an amazing ability to shed light without rendering too much judgment. In one of the best passages, the author attributes the proverbial failure of the ELF to its inability to reconcile the new with the old:

“The tradition of Hto-r’yto (questions and opinions) in the ELF, although frustrating to the veteran fighters and commanders and the leadership in general, was a very democratic tradition which allowed the rank and file to ask questions not only about their daily lives but also about the policies and direction of the ELF and the revolution in general. In fact, the Hto-r’yto was a contentious session between the commanders who for the most part, were illiterate veteran fighters, versus the relatively educated newcomers. It was exacerbated by the fact that the newcomers were mostly Christian and the veteran fighters mostly Muslim. Not only were the veterans unable to match the intellectual curiosity of the newcomers, they were completely unwilling. The reason being the veterans saw themselves as soldiers following orders from higher-ups, no questions asked; while the newcomers saw themselves as freedom fighters temporarily using military strategy to reach their aim: the independence of Eritrea. The newcomers never accepted being soldiers, and simply following orders was out of the question for them. These opposite views bred conflict.”

The book makes it clear that the ELF was a dysfunctional organization with an enormous potential to be a force of good had it run its course. It should have been reformed; but it fell primarily under the weight of its mediocre leadership who could not see beyond the tip of their parochial nose. The last straw that broke ELF’s back was EPLF’s “duplicity” that eventually led to the civil war. The EPLF’s duplicity and betrayal became evident when it conspired with an external power, the TPLF, to drive the ELF out of Eritrea, thus, fulfilling a long awaited prophecy of jebha kem chew kthaqQ ya, (ELF will melt away like salt), dubbed as tnbit Isayas, Isaias’s prophecy by ELFites.

With all its flaws and deficiencies, the ELF was a democratic organization better in tune with the traditions of the Eritrean people. “In the ELF, current affairs such as the civil war and other issues were debated freely and openly. That tradition was never discouraged, even in the middle of the civil war. One of the issues ELF fighters raised at Hatsina, for example, involved the notification of the family of the deceased or the martyred fighters. They wanted to know why the ELF no longer notified the families and instead allowed rumors to fly around.”

When was the last time the so-called Transitional Government of Eritrea exercised this kind of decency?

Perhaps our solution lies in combining the organizational prowess and militaristic discipline of the EPLF with the democratic and open culture of the ELF. For once, remaining closer to the center would do us great good. There is a lot we can learn from our recent past. Our goal should be to understand, if we are to be part of the solution. Read The Fighter’s Letter!

Buy the book at: Africa World Press or Amazon

Awate Forum