More Reflections on Alemseged Tesfai’s Epilogue

This is not a proper article but rather a collection of thoughts … I started off well, but I was too weak to continue.

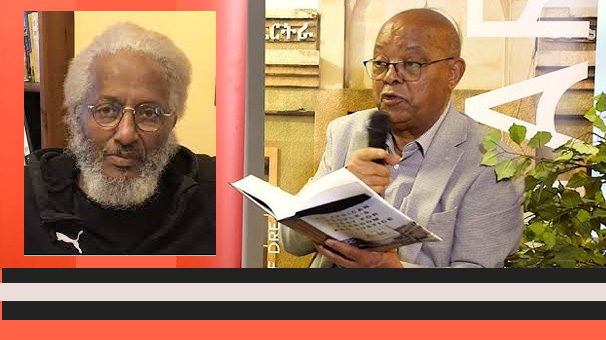

I was very surprised when I watched a video of a group of PFDJ supporters—the Eritrean regime’s party members—welcoming Alemseged in the embassy hall in London, clapping rhythmically in a rising crescendo, just as we used to when Isaias entered to give a speech during the so-called “good old days.”

That display gave me pause. It struck me with a twinge of discomfort and convinced me that our “Historiographer Royal” was breaking his silence to reveal where he stood in the current struggle—more likely on the side of the PFDJ than on ours.

Each clap felt like a slap across both cheeks—sharp and unrelenting. When he took the floor, preening like the prima donna of the PFDJ theater troupe, a wave of sadness washed over me. Flanked by embassy staff, he spoke with an air of authority—official, in the stiff, government sense of the word.

As that scene stirred my curiosity and eagerness to read his book, it didn’t take me long to get a copy—and I began reading right away. Within a few days, I had worked my way through it until I reached the much-dreaded epilogue on page 423.

It opened with: ‘Anything we say about the history of the Eritrean revolution, especially the armed struggle for independence, can only be brief, cursory, and tentative.’

“Brief, cursory, and tentative?! That’s a bunch of malarkey!’ I cried. This is a man who was born in 1944, lived through the Federation (1952) and Annexation (1962) periods, endured the Haile Selassie era (until 1974), took part in the armed struggle (until 1991), and has lived in Asmara for 34 long years since independence.

The next passage was even worse. He claimed that Eritreans everywhere are influenced by the “old factional rhetoric” [as they go after each other]. Does that mean I, along with my fellow human rights and democracy campaigners, ex-freedom fighters (from both factions), conscientious citizens, members of various civil society groups, and young people who recently fled Eritrea, are making noise and attacking each other because of the old Jebha/ShaEbia divide? That postulation coming from Alemseged flabbergasted me.

In my mind, I asked, “What about the living conditions in Eritrea that are driving our people to seek asylum everywhere?”

“What about the open-ended national service that is pushing our youth to flee the country?”

“What about the stifling atmosphere that pervades everyday life?”

“What about the new rulers who have our people by the throat?”

What about… what about… what about?

I addressed various issues regarding Alemseged’s epilogue in my previous article, titled “Why Alemseged, Why?” I feel exhausted just thinking about the mental effort it took to write it. I don’t allow myself to repeat points merely for the sake of discussion.

Let me try a different approach—albeit rather hastily. But I must warn readers: what follows may feel like a series of disconnected rumblings.

When I wrote the history of Woldeab Woldemariam, I believed it would help me better understand certain episodes in the lives of Eritreans—episodes shaped by motivations, consequences, and recurring patterns that have tripped us up as a people and led us into trouble. I felt deep sadness for our society, repeatedly jerked around by former rulers, only to end up under the rule of ex-freedom fighters who themselves became vicious oppressors.

It might sound like an exaggeration to some, but when I quietly reflect on what the PFDJ has done to the people of Eritrea, I cannot help but think of the decisions and processes it employed in shaping my hollow existence. I ask myself how much our esteemed historian truly understands of the decisions and processes.

Why did I ever believe that he would one day use his most powerful tool—his writing—to expose the crimes of Isaias and his regime to inspire us to tighten our belts in the struggle for justice?

How I wished that Alemseged would one day rise up on behalf of Eritreans, voicing his grievances and courageously confronting the regime—through his mighty pen—by calling out its injustices and demanding change. A poorly managed expectation on my part!

Yes, I once foolishly believed that Alemseged, like Edward Gibbon, the influential English historian, would one day deliver us from the PFDJ’s tyranny.

Now, here I am, stuck at my laptop, trying to write a proper response to those who, seemingly, are apologising for the man who made it clear to me—and, I’m sure, to others—that he is on the regime’s side.

I believe writers are like performers: they show off and seek attention from their readers, aiming to create an authentic and engaging experience. I do the same.

As a human rights campaigner, I add a certain dose of flair to capture attention. At times, I might get carried away and strike my opponent below the belt—but that comes with the territory.

Right now, I cannot produce paragraphs packed with lofty words that say very little. I’m low on energy, as I’m under the weather. Perhaps if you give me a few days, I’ll bounce back.

I’ll be content as long as readers—including my critics—recognize and share the concerns raised by Alemseged’s epilogue, which I referred to as ‘the epilogue of shame.’

I thought Eritrea, with one foot in the grave, would find in Alemseged its knight in shining armor—someone who would speak truth to power and deliver it from evil. How silly of me!

I cannot say much, at the moment, to those who took issue with my article or with where I posted it. Before I go, I will say this: where I posted it is a non-issue to me. My aim is to reach as many people as possible—both Eritreans and the international community. In our long struggle as campaigners, I am well aware of who reads what amongst us.

In the meantime, please nudge me gently to reflect more deeply on my shaky intellectual relationship with Alemseged—someone who, I feel, betrayed me and many others – and help me steady my unstable footing.

I thank Beyan for reviewing my views and for strengthening my arguments with his critique. He sounded to me as though he agreed that the epilogue was poorly written and wrong. That, in itself, is one way of getting the message across to Alemseged and to the wider public. The aim of this exercise is not to push Alemseged into a sea of trouble, but rather to remind him of the bona fide responsibilities of his role in our society.

Our esteemed author should not have placed the blame on the ELF for Eritrea’s ailments—past or present. For our readers’ sake, I should have dwelt more on the role the ELF played in Eritrea’s nationalist journey and armed struggle. In due course, I hope to highlight a few points to show that the ELF martyrs still reside in our collective psyche.

Alemseged believes in everything EPLF and nothing else. I think that is the source of my disagreement with what the man represents. He, more or less, clarified his stance by citing prevalent government policies in his epilogue as the pillars supporting the government’s steadfast administration.

I hope to recover and write some more soon.

Awate Forum