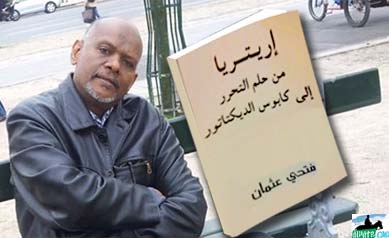

Fathi Osman and His New Book

Recently Fathi Osman (ፈትሒ – فتحي) published a book entitled, “Eritrea: From A Dream of Independence to the Nightmare of Dictatorship.” The book, written in Arabic, is composed of one hundred twenty-two page; Fathi has plans to translate it into English.

How did Eritreans, after they sacrificed so many lives and shed so much blood to be free, end up living in a dark tunnel under a one man dictatorship for over twenty years? How did the sacrifices of Eritreans produce the current situation?

Many Eritreans are asking the same questions in so many ways, and the author, Fathi, starts his book with a similar question. He then attempts to answer the question in twenty chapters–each an independent, yet, part of a series of articles that attempt to explain and answer the great Eritrean question: How did we end up in our present situation?

The author diligently digs into history and geography, and analyses the beginnings of the Eritrean armed struggle, goes through the intellectual and psychological inspirations of the two main struggle-era organizations, touches on the tribulations, the military feats, the sad and crippling moments, and critical mistakes that Eritreans committed on themselves.

The tone of the book, though calm and composed, at times, seems to push the reader into resignation, but it doesn’t. One expects to read nationalist bravado, but there is none. Instead, what the reader finds is plain, simple, dispassionate expression of the author’s views and his attempt to find answer to the grand Eritrean question: how did we end up in our present situation?

The author writes about the disappointments in a way that makes one feel nothing is insurmountable for Eritreans who went through ages of injustices, couldn’t take it anymore, and finally revolted and triumphed in 1991. However, overtaken by the euphoria of independence, they didn’t realize they had only accomplished half the job they set out to accomplish, and the dedication on the book sheds light on the part of the goal, freedom, that was not accomplished; the book is dedicated “to the noble Eritreans behind bars!”

The first parts of the book are analysis of the topographical and environment of Eritrea, and how the mode of economic subsistence, and geography, shapes the many characters of Eritreans differently. Fathi contends that “understanding the political phenomena should be based on an introductory study of the geopolitical realities.” Only then it’s possible to, “successfully present a structured analysis.”

The analysis leads to an explanation of the manifestations, of what transpired from the differences, resulting in the development of varying outlooks that the elite of the struggle era espoused, and which led the Eritrean organizations, and steered the struggle to the outcome that we see today. Though the author doesn’t believe that the diverse outlook was the only reason for the present state of Eritrea, he argues that the main difference is found in the background and the different source of inspirations of the cadres of the ELF and PLF. That difference has widened the gap between the elite of the two organization and then spread to the rest of Eritreans.

While those who led the ELF were mainly inspired by the events in the wider region surrounding Eritrea, the EPLF elite were mostly a product of the Haile Sellassie university, whose ranks was later augmented by the influx of people who joined them from the West beginning in the mid-seventies, responding to the less-talked-about call that Isaias made to Eritreans to join the EPLF to, “save what remains to be saved.”

The author concludes that the present crisis in Eritrea has its source in the nature of the PFDJ that was structured as a military organization where discipline, secrecy and hierarchical obedience ruled supreme. It had created a gigantic war machine devoid of a parallel development of a political institution. After independence, the militarized-mentality of the PFDJ failed in coping with the political requirements of nation building with all its complexities.

“Looking back at the history of the EPLF from the seventies until Independence Day, it was politically ascetic and militarily colossal. It began walking on two legs: one a lively, a fully developed muscular military leg, while the other leg an atrophy, not totally paralyzed but can be described as a crippled leg.”

The book contains ample veneration of the military feats of the EPLF, describing it as, “bold and daring [feats] whose loud-noise echoed inside and outside Eritrea, but in comparison, its political activities were bashful and introvert. That nature of the organization extended to the post-independence phase; and its result is the current crisis of the organization.”

To elaborate and solidify that argument, the author poses a question: “what is the political equivalent of Nadew Iz that the British historian Basil Davidson likened with dien bian phu, the mystical [Vietnamese] battle of 1958?”

Of course, the PFDJ doesn’t have an awe-inspiring political achievement equal to the victory over the Ethiopian army at Nadew Iz.

Generally, the military is always subservient to the political administration; in the case of the PFDJ it is not. The author demonstrates the result of that weakness by citing an example from the 1998-2000 border war with Ethiopia when, “the president gave his orders to the army to retreat on the face of the Ethiopian invasion that resulted in the fall of Tessenei, Barentu and Senafe, while Osman Saleh, the commander of the Assab sector disobeyed the order,” and defended the region from the attacks of the Ethiopian army. The author emphasizes on these events to shows that the fire of the organization’s military might was still alive while its political weakness was evident.

He further explains: from 1994 to 2000, the PFDJ turned the saying of Clausewitz, the famous strategic thinker, that states, “war is an extension of politics,” upside down. Thus, it seemed to believe, “politics is an extension of wars.” In short, the EPLF created a military elite capable of great achievements, but it didn’t produce an equally talented political elite. And that, the author argues, is the hindrance, the inability of the organization to deal with the political requirement of nation building.

During the nation building stage, Fathi writes, the EPLF immersed itself in, “an attempt to produce the conditions of its historical existence” that prevailed in the seventies. And he likens that to a servant who gives birth to her master, or to a snake that swallows its tail. He writes, the organization found itself face to face with the tasks of building a state, tasks and challenges for which it was ill prepared, except an armament in the form of a slogan: “we are able to achieve the miracle of development just like we were able to achieve the miracle of independence.”

But before long it was surprised when it discovered it didn’t have the political, institutional and conceptual structure to face the challenges of state building. At the same time, other observers of the situations discovered that the PFDJ didn’t have the “Will” to build state institutions—and that should not be mistaken with the building of huge bureaucratic establishments, but genuine intentions to expand the political participation in the task of nation building. The absence of this kind of intention is what is clearly evident after twenty years of independence.

The author gives a vivid example of the top-down developmental attempts: “in Sedoha Ella I saw classrooms that have become shades for goats because there were no students there.” He explains this as a result of misplaced priorities, ill assigned roles, and mis-allocated resources—aspects of leadership in which the PFDJ failed.

In the past, after years of peaceful struggle, Eritreans were convinced that, “a right that’s not backed by the gun, is a lost right.” And in 1961, they raised their guns to assert their right to self-determination. That struggle was not an end in itself, but a higher and noble vision to pursue the goal of a dignified life. Unfortunately, in the hands of the PFDJ, the gun has become both a means and an end. And that’s why all the confrontations with Eritrea’s neighbors are, “PFDJ’s empty and deadly attempt to produce the conditions for its existence, and its old military superiority.”

A good portion of the book addresses the issue of secularism as espoused by the PFDJ. Fathi delves into “civic religiosity” that the West venerates; the high secular values, such as liberty, equality and fraternity, which provided the ground for the establishment of democratic consensus that represented the pillars for a liberal society, which has become the foundations of Western Democracy. He believes that the PFDJ doesn’t approve of such a democracy or its African duplicates, as a complete or just democracy, thus espousing social democracy over political democracy. It believes that political democracy is the last manifestations of social democracy, and that is why the leaders of the PFDJ repeat the president’s line: “we do not believe in the democracy of ballot box.”

Social justice, the author explains, is a manifestation of democracy and it is the acceptance of the natural rights of human beings. It’s based on the recognition of the rights of others, the conviction that there should be an equitable distribution of rights and obligations, resources and opportunities—a conviction that was never espoused by the PFDJ. The only equality the PFDJ achieved for the components of the Eritrean people is the equal distribution of opportunities to face the bullet of the enemy, and the equality of dying.

PFDJ’s claimed national secularism didn’t produce civic religiosity that the values of the nation requires, and which is the genuine concept to establish secularism. Instead, its secularism is superficial, a surface-only phenomenon, shallow, because its requirements are difficult for the PFDJ to attain. The author explains this with an Arabic saying, “keifa yesteqeemu a’ zil wel Oudu a’aweju?” How can a crooked stick cast a straight shadow? He adds, “Secularism requires the separation of religious from state institutions, but there is no state institutions in Eritrea from which one can separate the religious institutions from it.”

The author delves into other thorny Eritrean issues: the “national service”, the destruction of Asmara University and how the students are scattered all over Eritrea with the pretext of spreading education, and how that represents the severing of the multi-layered relations between the youth and the PFDJ whose representatives are roaming the world to attract the youth to what is known as YPFDJ. He explains how the multi-layered relational crisis between the PFDJ and the people is the cause of the “Political Gangrene of the organization, a disease that denies the supply of blood to its dried up limbs which now have no cure except amputation.”

Fathi doesn’t have any kind words for the Eritrean president either, and writes, “Isaias doesn’t resemble any of the tyrants [who lived] through the ages except Emperor Nero who tuned his guitar strings to the sound of the raging flames, when he burned Rome.” The author describes Isaias as a man who is driven by a typical selfish attitude, a man who lives by the maxim of tyrants: “après moi le déluge.”

After every few pages, we find a description of Isaias’ character and an analysis of the mechanism he used to climb to the helm of power in today’s Eritrea. A chapter entitled A Legacy of Tyranny and Hopelessness reads as follows:

“After twenty years of independence, how can the state of affairs in Eritrea be described under tyranny? Had the Eritrean womb known that it will give birth to a handicap like Isaias Afwerki, it would have certainly hoped it was barren to avoid that birth. Is this a cruel statement against the man? Absolutely not.

It is cruel to the extent of cruelty that he showed in his long journey, since he joined the revolution, and the cracks he created among the youth and continuing when he has approached seventy. It is a phase in which the road of the journey rolled to get him to the reign of power where he produced an absolutist rule that neither the old generation of Eritreans nor the new ever imagined.”

In another part he writes, “Everyone knows the driver and his reckless driving record and the cliff that the country is running into. Let’s look at the surroundings in which the Eritrean vehicle is running towards a cliff: there is no one who would regret it if Eritrea loses its independence except the Eritrean people…. When Eritrea lost a quarter of its territories in the war with Ethiopia, who among the neighboring countries stood with it or supported it? And if that scenario is repeated today, who will stand beside it when it is more isolated than the previous time?… today Eritrea doesn’t have a real friend who worries about its sovereignty and territorial integrity, and those who spuriously smile for Isaias in Khartoum are at the same time wishing his end comes sooner than later. The scenario of disaster is there… and that should be the concern of every Eritrean who loves his country.”

Fathi conclude a chapter with a statement that reads more like an appeal: “…any citizen can identify a component of the [present] crisis because it is a multi-dimensional crisis… at the end, [the nature of the crisis] presents a legitimate pretext to end the PFD’s rule in Eritrea.”

Education:

Fathi Osman is had a degree from Kuwait University, English Literature; Higher diploma in Diplomatic Studies from the The National Center for Diplomatic Sudies, Khartoum; Diploma in Peace and Development Studies from Juba University; also Master’s Degree in Peace and Development Studies from the University of Juba

Work History:

Eritrea AlHaditha, Eritrea: Journalist (1994-1996)

Hanish Islands Commission, Eritrea: Manager, research unit (1996-1998)

Legal Adviser’s Office, Presidential Office, Eritrea: Manager research unit (1998-2003

Eritrean Embassy, Islamabad: Manager, political affairs (2003-2004)

Eritrean Embassy, Riyadh: Manager, political affairs (2004-2012)

Awate Forum