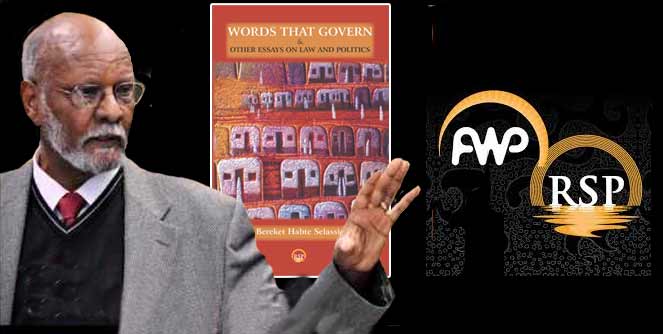

Book Review: WORDS THAT GOVERN

BooK: Words that Govern and Other Essays in Law and Politics

Author: Bereket Habte Selassie

Price: $24.95

Pages: 256

Year: 2018

Publisher: Red Sea Press

WORDS That GOVERN is written to the budding young democratic prince—a citizen who has to govern him/herself under the revolutionary and yet old idea of self-government—by a scholar-practitioner, who was, in his long and rich career, fully engaged in the subject. In a career that spanned six decades, Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie had the opportunity to work on, mull over and write about the most important perennial issues that have consumed the best minds in the history of mankind. They are perennial because each and every generation has to deal with them, and Eritreans are no different. Words encapsulate our highest ideas and aspirations and it is with words that we best express our humanity and govern ourselves. Freedom of opinion and the right to freely express them are the two intertwined pillars of a free society.

Public conversations—debates, dialogues, diatribes, and discourses—must thrive and continue to thrive if liberty is to live in perpetuity and tyranny is to be kept at bay. Liberty is the responsibility to self-rule without any undue constraints and interferences. It is the condition that ensures, in the words of Lincoln, that “the government by the people, from the people and to the people” does not perish from the earth. Liberty requires an informed and educated citizenry. An educated citizen is easy to govern and hard to enslave. No wonder that tyrants are invariably anti-education and are often-times ill-educated themselves. Look no farther; Isaias Afwerki is the embodiment of this malaise. Of the top ten least educated presidents in Africa, Isaias Afwerki ranks number eight. Eritrea, under Isaias Afwerki’s colossus mismanagement, ineptness, and mediocrity, has become a pariah and a poster-child of what is wrong with Africa: a place of ignorance, poverty, under-development, indebtedness, war, conflicts, and stagnation.

Stability and peace, the author argues, are essential to nation and state-building. The genius of any political life is the recognition that nothing is permanently locked, and is, thus, subject to be cautiously amended and appended by each and every generation. Every political document suffers from the faults of omission and commission. “When a nation is engaged in making or amending a constitution, the expectation is for such parochial, constituency interests to be submerged beneath a higher national agenda,” (pg. 23) but, in the final analysis, it has to reflect the agenda of the powers that be. To make it work, it will require patience, commitment and fortitude from all concerned parties.

The doors of self-governance are open and change all the time because they are inherently imperfect and need to be improved upon. But as long as people live another day to fight and there are mechanisms for redressing societal grievances, there is no need to rock the boat. This is the basis of modern constitutional engineering, and certainly, the basis of Eritrea’s ratified constitution, whose principal author and chair of its Constitutional Commission was Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie. Constitutional engineering has become, “the principal method of achieving democracy” (pg. 2) in Africa and elsewhere.

On many occasions, I have heard Dr. Bereket quote Benjamin Franklin who at the end of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 was asked by Mrs. Powel of Philadelphia, “Well, doctor, what have we got, a republic or monarchy?” and Ben Franklin retorted, “A Republic if you can keep it.” The implication is that Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie and his Constitutional Commission have given us a constitution if we, the citizens of Eritrea, can just keep it.

By refusing to implement the “popularly drafted and ratified constitution,” Isaias Afwerki has sentenced it to still-birth. But as long as the fight for liberty is on, the constitution will enjoy currency—it is an integral piece of the most optimal solution. “The general consensus now is that the ratified constitution can serve as a crucial weapon in the struggle for democratic change and that it can be amended to accommodate the demands for any necessary change.” (pg. 199) The implementation of the constitution is a win for liberty and a loss for the tyranny.

The ratified constitution is a friend to those fighting for liberty and an anathema to Isaias and his coterie of Stepford minions. Despite its lack of implementation, the constitution is “a potent and morally compelling force.”

Democracy is the best way to institutionalize liberty. The democratic prince must, therefore, possess certain virtues among which the most important is the eternal vigilance to cherish, preserve and protect liberty. In the Discourse, Machiavelli points out “that no institution can be long preserved, but by the frequent recurrence to those maxims on which it was founded.” WORDS THAT GOVERN echoes similar sentiments.

The problem with Africa, as President Kennedy would say, is that “liberty without learning is always in peril and learning without liberty is always in vain.” There was something fundamentally flawed with the democratic experimentation in Africa. None of them were home-grown. Learning implies adaptation and internalization and there was none of that. Africa was not the architect of its own learning.

In the preface to his famous book, THE PRINCE, Machiavelli urged Lorenzo De’ Medici to accept his humble gift in which he has ventured “to discourse and lay down rules concerning the government of Princes.” His authority rested on his practical experience and study. “For as those who make maps of countries place themselves low down in the plains to study the character of mountains and elevated lands, and place themselves high up on the mountains to get a better view of the plains, so in like manner to understand the People a man should be a Prince, and to have a clear notion of Princes he should belong to the People.”

Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie has seen the political landscape of Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Africa from the top of the mountain and from the bottom of the valley. He has seen it all: the hope and despair, the ebbs and flows, the boom and bust of nation-building and political and economic development. He has had a front-row seat at the so many revolutions which were inspired by the loftiest and noblest of ideas only to end up joining a long list of Africa’s unfulfilled aspirations. In his experience, he has come to believe “that, far from being mutually exclusive, the two aspects—the academic and the practical—are mutually enriching.” (pg. 136)

The long winter of despair and disappointment has not yet prevented hope and optimism from springing eternal in this hopelessly romantic revolutionary and pan-Africanist, who still, in his sunset years, proudly sings praises to the ideas of human dignity, liberty, rule of law, peace, democracy, self-determination, and social justice. The more things have changed, the more they have remained the same, but this pessimistic observation of the intellect only serve to correct the Panglossian optimism of the many and it is vital and necessary.

The failure of implementation, as the book repeatedly demonstrates, does not negate the saliency of these ideas to Africa and humanity in general. “A deviation from the path does not diminish the value of the path, nor the goal at the end of it.” (pg. 4) He approaches the failures and disappointments with empathy and understanding for he is intimately aware that many good people had labored under the burdens of history, oppression and enormous internal and external challenges, which made success an elusive prospect.

Although he understands that failure might have been inevitable, he does not condone crimes committed in the process: they were categorically inexcusable. The “leaders have become a cabal of self-perpetuating oligarchy, playing Russian roulette with its fortune and the lives of its people.” (pg.171) “What should be done to leaders who are the cause of much tragedy and human suffering? And what is the role of ideas and institutions, both modern and traditional, which enable such leaders to commit acts of horror?” (pg.62)

Morality and God loom large in his outlook and love, mercy, forgiveness, compassion, and understanding become instrumental in healing wounded nations and reconciling divided societies. There is no justice without mercy, no understanding without empathy, no comity without compassion and no reconciliation without forgiveness. “An orgy of blame game may satisfy some egos but…far from helping to heal a wounded nation, it will do irreparable damage.” (pg. 172) Flexing muscles make us strong and relaxing them better. The key is to recognize that “Every tragedy contains a Potential for Redemption.” (pg. 76)

In this small, intelligent and graceful volume, Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie, bequeaths his life-learned lessons to the modern and emerging democratic prince, but not in a fashion that smacks self-aggrandizing. Anyone who knows the author up close and personal could testify that he is nothing but humble and in Bereketesque manner, WORDS THAT GOVERN is saying that “a dwarf sometimes may see that which a giant looks over.” Throughout his career, he has learned from people of all walks of life and believes, like Galileo Galilei, that no man is too ignorant not to learn from.

WORDS THAT GOVERN is a book that would make one rediscover and savor the importance of old ideas such as wisdom, prudence and statesmanship. The book is a collection of essays—instant classics—told with a modern flavor. The topics range from Democracy and Peace in the age Globalization, Aspects of Language, Law, and Politics, Making Sense of National Boundaries, Crime and Punishment, Human Rights and Humanitarian Law, Self-Determination, Unity for the Greater Good, When the Protector Becomes Predator, and Religion and Nationalism.

WORDS THAT GOVERN asserts that the “mark of mature statesmanship is to seek a solution satisfactory to both sides,” (pg. 155) and that “moral and normative principles do not always prevail over power politics,” but it helps to know that politics is “part serious and part theatre.” In the words of the 19th British statesman Benjamin Disraeli, “It is with words that we govern men,” and hence the title of the book under review.

Wisdom matters and in a moment of ambiguity, the democratic prince should always raise the proverbial question of how hedgehogs make love and the answer will invariably be: very carefully.

To purchase the book, click here: Words That Govern or Amazon.co.uk

Semere T. Habtemariam is the author of “Reflections of the History of the Abyssinian Orthodox Tewahdo Church” and “Hearts Like Birds.” He can be reached at weriz@yahoo.com

Awate Forum