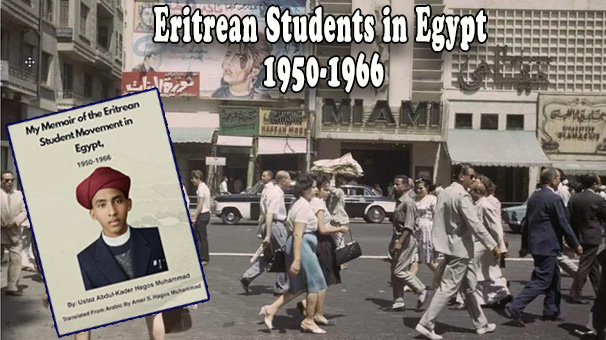

Book Review: Memoir of the Eritrean Student Movement in Egypt (1950–66)

In My Memoir of the Eritrean Student Movement in Egypt, 1950–1966, Abdul Kader Hagos Muhammad offers more than a mere reminiscence. He provides a participant’s chronicle of a formative but often overlooked chapter in the making of modern Eritrean nationalism: the years when young expatriate students in Cairo began translating identity into organization and organization into political purpose.

In 169 pages, divided into 10 chapters and with more than 30 historical pictures, some published for the first time, the author navigates us through the journey of Muslim Eritreans to Egypt to study in Arabic and those of Christian Eritreans as well, who came to Egypt for religious studies in the Coptic Church institutions in Egypt.

First published in Arabic and now available in English through the efforts of translator Amer S. Hagos Muhammad, the memoir spans the period from 1950 to 1966.

Its narrative follows the evolution of informal student gatherings into structured associations, culminating in the establishment of what became the nucleus of Eritrean political activism abroad. The author writes plainly, at times almost conversationally, resisting literary flourish in favour of testimony. That simplicity, however, is also the book’s strength: it conveys the immediacy of lived experience.

Students as political actors

Cairo in the 1950s was a magnet for anti-colonial movements, a city where African and Arab futures were debated in lecture halls, cafés, and diplomatic salons. Eritrean students—many of them at Al-Azhar University—absorbed these currents while confronting the uncertainty of their own homeland’s fate.

Hagos describes how practical concerns—housing, language study, financial support—gradually intertwined with political ambition. The student club became a welfare centre, a debating chamber, and, increasingly, a platform for national advocacy. In his telling, activism did not arrive fully formed; it grew through meetings, visits from speakers, disputes with Ethiopian representatives, and the slow forging of solidarity among young people far from home. It was there that a charitable student organisation became the first Eritrean Student Union in the country’s history in 1952.

Memory and nation-building

What distinguishes this memoir from retrospective nationalist histories is its granular texture. We encounter fundraising drives, committee elections, friendships, rivalries, and the daily improvisations required to sustain an institution. Major historical developments appear not as abstractions but as pressures filtering into the routines of student life.

The book also captures the era’s widening horizons. Hagos recounts representing Eritrean students at the World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow in 1957, a moment that situates the movement within a global landscape of solidarity politics. Such passages reveal how Eritrean activism was both intensely local and unmistakably international.

Between witness and argument

Readers will notice that the volume is not neutral. Like many memoirs born of liberation struggles, it advances firm interpretations of responsibility, legitimacy, and historical agency. Ethiopia’s role is presented in stark terms; Egypt’s environment is remembered as enabling and generous. Yet even where the argument is emphatic, it remains valuable as evidence of how participants themselves understood events. Historians may wish for more engagement with competing perspectives, but they will also recognize the rarity of such first-person documentation. Movements often leave behind manifestos and communiqués; fewer preserve the intimate reflections of those who built the scaffolding.

Translation as recovery

Bringing the text into English significantly broadens its reach. For non-Arabic readers, this edition opens access to a foundational narrative that has circulated for decades within Eritrean intellectual circles yet remained largely invisible internationally. In that sense, the translation functions as an act of archival recovery.

Hagos does not claim to be a professional historian. He presents himself, instead, as a witness. But witnesses do matter. Through modest prose and careful recollection, My Memoir of the Eritrean Student Movement in Egypt, 1950–1966 illuminates how nationalism can germinate in dormitories and discussion groups long before it reaches the battlefield.

For anyone seeking to understand the intellectual prehistory of Eritrea’s long struggle, this memoir is indispensable—not because it closes debate, but because it gives that debate a human voice.

The book is available in paperback and e-book on Amazon:

My Memoir of the Eritrean Student Movement in Egypt, 1950-1966, is available on Amazon.com.au

Or contact: Muhammad, Abdul-Kader Hagos, Hagos, Amer Saleh,

Awate Forum