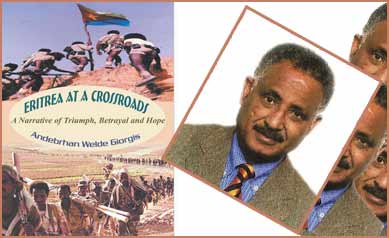

Andebrhan Welde Giorgis’ Book: A Commentary

Title: Eritrea At A Crossroads: A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal and Hope

Author: Andebrhan Welde Giorgis

Publisher: Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co.

ISBN: 978-1-62857-331-2

Pages: 661

Price: $36.50

Website: http://sbprabooks.com/AndebrhanWeldeGiorgis

Eritrea At a Crossroads is a compelling story of people who had waged an epic struggle for self-determination and succeeded, albeit for a short time, to represent “a world-historic heritage of peoples fighting oppression.” The experience of the once-promising-nation is intricately entangled in a duality of extremes; it “embraces an array of commendable achievements offset by lamentable failures.” The long and protracted armed struggle was a tribute to the human spirit of defiance by people who were fully mobilized to protect the integrity of autonomy and self-rule, but, who in the process and at the finishing line, took a wrong and fatal detour that is robbing them of their humanity and what was noble and dignifying. “Sadly, we ended up with the opposite of what we fought for. The contradiction hurts like a permanent cut with a blunt knife.”

The book narrates beautifully and intelligently Eritrea’s “story of heroic triumph in struggle and of dismal failure in victory.” It is the story aptly encapsulated by the title of the book Eritrea At A Crossroads: A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal and Hope.

It is Isaiah-like lamentation where the author saw the men of Eritrea fall by the sword and the mighty ones in battle, and Mariam-Asmereyti was lamenting and mourning, for deserted she sat on the ground. “The country reels under tyranny, the people languish in poverty, and the youth continue to flee in droves. Dictatorial, incompetent, and predatory, the regime perpetrates domestic repression, thrives in regional confrontation, and provokes international isolation. It has betrayed the rasion d’être of the armed struggle, despoiled the sacrifices of our martyrs, and miscarried the vision of building a free, democratic and prosperous Eritrea that stands out as a bright star in the African constellation.”

Liberation was made “possible at a staggering cost in human life and suffering” and the “huge sacrifices made on the way” could only be vindicated by “heralding a bright future shinning with peace, freedom, democracy and prosperity.” It was the simple recognition of this truth that the immediate post- independence years “generated a very high level of national excitement verging on euphoria, and triggered an explosion of optimism, setting the country ablaze with the flames of hope and expectation.” In the minds of Eritreans it was a foregone conclusion that it was time “to reap the benefits of liberty.” As a first step towards realizing the dream, the strategic planning of nation-building was set in motion:

The National Charter outlined a holistic vision of Eritrea, encapsulated in six basic goals and six guiding principles. The six basic goals are national harmony, political democracy, economic and social development, social justice, cultural revival, and regional and international cooperation. The six basic principles are national unity, active participation of the people, the decisive role of the human factor, struggle for social justice, self-reliance, and a strong relationship between the people and the leadership. The National Charter embedded democracy, justice, and prosperity as essential elements for the improvement of the human condition of the Eritrean people. (pg. 161)

The national Charter, the Macro Policy paper and the Constitution of Eritrea are consistent with the objectives of the National Democratic Programme of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), the Front that led the armed struggle for liberation to victory and formed the government upon independence. These policy instruments set the overall framework to guide the integral process of national-building, state construction and sustainable development in the new Eritrea. They aimed to enable the government to build a constitutional, democratic and developmental state able to deliver the rule of law, responsive governance, and prosperity (pg. 325).

Andebrhan Welde Giorgis does not spare any efforts to assertively claim that “liberation was pursued as a stepping stone for independence; independence was sought to enable the creation of a new democratic state whose hallmarks would be the pursuit of liberty, progress and prosperity, under a government constituted on the basis of the free exercise of the Eritrean people’s right to self-determination.” The vehicle of nation-building was stuck in first gear; finally coming to screeching halt under the pretext of the border war. Tragically, the regime that the author helped to install has gone rouge. A flagrant betrayal of the principles, which had inspired and animated Eritreans’ epic struggle, has led to a road of perdition where the long-awaited Exodus is away from the Promised Land and not towards it.

But it is also a story of hope and redemption where a renewed commitment, now and in the future, would lead to another more impressive victory by people accustomed to win against all odds. “It will not be out of reach for a reformed Eritrea to replicate, on a small scale, China’s remarkable progress in achieving relative prosperity and improved standard of living for a large and growing proportion of its huge population.” Andebrhan Welde Giorgis is a true believer who proudly clings to the ideals of his revolutionary youth that took him from the peaceful academic halls of Harvard University to the rugged mountains of Sahel, where, in the words of Roy Pateman, even the stones were burning. The intensity of conviction is truly a source of tremendous power; faith moves mountains. “It was the firm conviction that liberty, dignity and prosperity would remain elusive dreams under continued Ethiopian occupation that drove tens of thousands of Eritrean youth to the field, lent the armed resistance of a powerful new impetus and ensured final victory.”

The story of Eritrea’s thirty-year war of independence is one of great endurance, stoic self-sacrifice, and remarkable resilience driven by abiding faith in liberty, justice and a bright future, in defiance of superior forces and the odds. It is an amazing story of great human endeavor, heroic personal choices and selfless sacrifice: people abandoned families, interrupted careers, gave up education, and forfeited livelihoods to fight for freedom. (pg. 623)

Eritreans’ indomitable spirit and sheer defiance against odds is not dead; it is slightly buried by a series of setbacks. It needs to be brought back to the surface and tapped into. It is in the revitalization of this Eritrean character where victory lies, and it is in this victory where Eritrea’s hope lies. Andebrhan Welde Giorgis is the personification of this Ertrawi niH; after more than four decades of public service, he is still globetrotting to make a final push for the noble causes he spent a life-time fighting. “That the Eritrean people won remains a living testament to their determination, perseverance, and resilience in the face of great odds.” Although Andebrhan Welde Giorgis admits that there is “no silver bullet” to bring the desired change, he adamantly cautions that “only an internally driven and all-inclusive reform process, guided by effective political initiative to reconstruct the State on a new basis, would rectify the prevailing bleak state of affairs and reverse Eritrea’s on-going comprehensive decline to ensure a bright future for the Eritrean people.”

Eritrea At a Crossroads is the story of Eritrea’s past, present and future set against the “backdrop of lifelong engagement” in which the author “seeks to shed some light on the fundamental disparity between the ideals and objectives of the historic struggle for liberation, on the one hand, and the reality of independence, demonstrating the failed policies and practices of a dysfunctional government, on the other.” In the words of Baroness Kinnock of Holyhead, “Eritrea at a Crossroads is both a personal story and a unique expose of the failings of a Government which has brought misery and suffering to its people.”

It is hard to escape the poignancy of a story told from “the prism of an insider’s knowledge and insight,” and Eritrea At A Crossroads is nothing but intimate. Andebrhan Welde Giorgis was the ultimate insider. The lure of a first-hand account by one of Eritrea’s best educated revolutionaries and seasoned diplomats is irrepressible. The heightened sense of what-is-in-store-for-me makes the book a page-turner and turning the last page is literally and metaphorically a milestone. It is the same feeling one experience upon reaching the summit of a mountain—a holistic look of the landscape one has left below.

The voluminous book is rich in details and insights that will make every Eritrean scream with pride as well as shame. But the book is not just a memoir, although the autobiographical notes are priceless. Andebrhan Welde Giorgis’ Eritrea At A Crossroads: A Narrative of Triumph, Betrayal and Hope is written from “a desire to contribute to the existing body of knowledge about Eritrea and the Eritrean people, both historical and contemporary,” but “beyond Eritrea, it is intended to contribute to a greater knowledge, deeper understanding and more rigorous debate of the root causes and key drivers of the essential fragility of the prototype contemporary African state.” For the most part, it is mission accomplished. He shows with some anecdotal evidence “the existence of an autonomous Eritrean history, the feasibility of a discernible indigenous Eritrean culture worthy of identification and accurate analysis, or a distinct psychological makeup of Eritrea as a shared homeland of the Eritrean people.” The history part was not his best suit. There is no independent Eritrean history outside the greater narrative of Abyssinia. Having a shared history with Ethiopians is neither an ever-lasting Covenant to stay together nor a license for divorce; what matters is self-determination and interest; and our interest as the author rightfully asserts is in regional integration and collaboration.

The freedom fighter’s scholarly pursuit cannot be separated from his life-time activism and his intention “to stimulate informed political debate regarding the prevailing situation in Eritrea and the way forward” is only what the situation calls for and what reason sanctions. It is a clarion call by an Eritrean freedom fighter for a constructive engagement in the “internal debate on the future of Eritrea,” and the “issues that have matured and become ripe for open discussion without compromising Eritrea’s national security (as distinct from regime security), the drive for internal change, or the safety of former comrades-in-arms and colleagues.” It is a fervent call for change tempered by wisdom and experience.

Andebrhan Welde Giorgis reaffirms unapologetically “the need for a fundamental rethinking of Eritrean politics and for reform to reconstruct a functional state, in line with the ethos and transformational goals of the armed struggle.” The call to go back to the revolutionary roots and to the “promises of freedom, democracy, justice and prosperity, for which the armed struggle was fought and great sacrifices made,” may seem to the casual observer not revolutionary enough, a bit backward-looking and conservative, but his potent arguments are transformative and most importantly will resonate with the many veterans and the public at large who share his “sense of profound deception and disappointment.”

Eritrea At a Crossroads is a timely and important book for those of us who are interested in preserving, cherishing and celebrating Eritrea’s epic struggle. “At the core message of this book celebrates the war was fought for freedom, democracy, progress and prosperity.” It reaffirms the overall goodness and beauty of our heroic struggle while simultaneously decrying its negative excesses. Andebrhan Welde Giorgis condemns without any equivocation “the constant use of force as a means to settle internal disputes” not just as a matter of historical record but because, “Regrettably, the malignant practice that bedeviled the evolution of the armed struggle has given rise to a political culture of extreme intolerance of pluralism that disparages independent thought, criminalizes divergent opinion and equates dissent with treason and treachery in post-independence Eritrea.” The author’s goal is neither to romanticize the ghedli nor to denigrate it but to simply celebrate its goodness and to “prevent the recurrence of the mistakes of the past” by drawing the right lessons.

Despite profound disappointment with the rise of dictatorship and the reign of misery in Eritrea however, I am very proud to have dedicated my life to the struggle for liberation and to the cause for the emancipation, progress, and prosperity of the Eritrean people, as a freedom fighter during the war and as a public servant after independence (pg. 635).

Andebrhan Welde Giorgis, “as a veteran of the war of liberation and a founding member of the EPLF Central Committee…admit(s) a profound sense of disappointment and a painful awareness of shared responsibility in the betrayal of the programmatic objectives of the armed struggle, the promises of liberation and the expectation of statehood.” The decision to go into exile was the most agonizing experience to this freedom fighter who considers it his highest “honor and privilege to serve with Eritrean patriots across generations whose personal courage in the struggle for self-determination, political commitment to the cause of liberation, and the concern for the welfare of the people remain unequalled,” but “the existential contradiction between the values I (he) cherish(s) and the sense of guilt from continued association with a government whose actions I (he) detested gnawed my (his) conscience and denied me (him) inner peace.” Andebrhan Welde Giorgis clearly states that he bears his “share of blame, responsibility, and pain for Eritrea’s present predicament.”

Andebrhan Welde Giorgis’s book Eritrea At a Crossroads will be read by my four children, those who are old enough and those who have to do a bit of growing, so they can learn the reasons many of their relatives and particularly their grandfather, abandoned families, interrupted careers, gave up education, and forfeited livelihoods to fight for freedom.

On behalf of the many that are no longer with us, I say many thanks to Andebrhan Welde Giorgis for giving them the tribute they deserve.

Awate Forum