Memory, Martyrdom, and the Eritrean Struggle

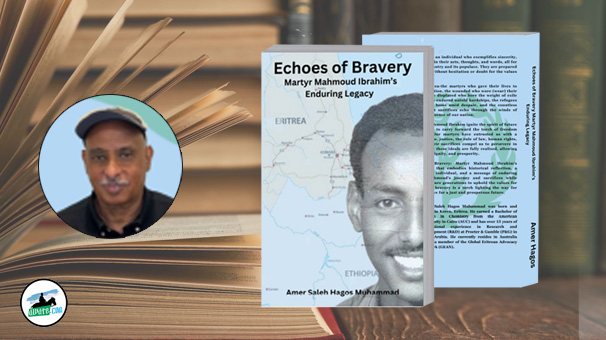

In Echoes of Bravery: Martyr Mahmoud Ibrahim’s Enduring Legacy, Amer Hagos (2025) constructs an impassioned, meticulously researched biography that is as much a personal tribute as it is a national archive. The text is a powerful act of recovery, of memory, of dignity, and of justice, situating Mahmoud Ibrahim, affectionately known as Cicchini, within the broader framework of Eritrea’s liberation history, while simultaneously challenging the erasure of local heroes from official historiography.

Structured across eight parts and over 300 pages, the book blends biography, political analysis, archival excavation, and oral history. Mahmoud is not portrayed as a lone, mythic hero, but rather as the embodiment of a collective pulse, a figure whose martyrdom during a fratricidal conflict in 1972 signifies both profound sacrifice and the tragic internal fractures that marked Eritrea’s long road to independence. This moment, central to the biography, reveals a tension that is crucial to understanding the unfinished nature of Eritrean liberation.

Amer’s prose is heartfelt and reverent. The biography opens with a stirring dedication to martyrs, refugees, and the wounded—those rendered invisible by dominant narratives yet whose resilience shaped the nation’s destiny. This ethos of communal remembrance runs throughout the text, enriched by interviews, historical context, and detailed documentation of early nationalist movements such as the Muslim League, the Liberal Progressive Party, and the foundational figures of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF).

One of the book’s most valuable contributions is its decision to be written in English. Amer articulates this choice early on: to reach younger Eritreans in the diaspora, to foster cross-linguistic and cross-generational understanding, and to invite non-Eritrean readers into Africa’s broader decolonial histories. This choice democratizes the story and places Mahmoud Ibrahim in dialogue with the internationalist tradition of anti-colonial figures, from Amílcar Cabral to Patrice Lumumba.

What sets Echoes of Bravery apart is not only the depth of its research but also the intimacy of its voice. Amer is no outsider to the world he describes. Having grown up in Keren’s Hillat Sudan, where the story of Cicchini lived in oral memory and collective grief, he writes with emotional urgency. This is not an academic biography cloaked in detachment; rather, it is a grounded act of restoration, one that reclaims memory and challenges silence.

Amer’s multi-layered approach is exceptional. He doesn’t limit himself to recounting Mahmoud’s life. Instead, he situates that life within a broad and complex landscape: the political ferment of the 1940s, the annexation of Eritrea by Ethiopia in 1962, and the emergence of armed resistance led by figures such as Hamid Idris Awate. He navigates Mahmoud’s training in China, his grassroots leadership in the field, and the painful fissures within the ELF with honesty and analytical clarity, thereby avoiding the sanitized or selective versions of history too often presented.

Chapter 2 stands out as particularly poignant, interweaving recollections from comrades and family members with reflections on sport, faith, and the broader political atmosphere. In particular, the influence of General Abboud’s Sudanese regime on the Eritrean struggle. These humanizing details offer a full portrait of Mahmoud: not just as a martyr, but as an athlete, a brother, and a dreamer.

In the later chapters, Amer expands the lens to engage with regional geopolitics: U.S. imperial interests, Ethiopian propaganda, and the intellectual divisions within the liberation movement. His inclusion of lesser-known revolutionaries, slain intellectuals, and student activists such as Dr. Fitsum Ghebre-Selassie adds depth and credibility to the historical narrative.

Perhaps the most affecting section is the “Golden Jubilee Commemoration.” Here, Amer makes a sobering argument: that while Eritrea has achieved territorial independence, political freedom remains elusive. The jubilee becomes a solemn moment of reckoning—an invitation to remember, but also to act. Mahmoud’s legacy is not entombed in 1972; it reverberates into the present, urging a new generation to grapple with memory, accountability, and the unfinished work of liberation.

Throughout, the tone remains humble. There is no slide into hero-worship or nationalistic triumphalism. Amer insists instead on human dignity, on naming the names, recording the voices, and reviving a silenced past.

In a region where history is often manipulated, forgotten, or erased, Echoes of Bravery stands as a monumental act of remembrance. It offers not only a biography but also a mirror to Eritrea’s soul: wounded, proud, fractured, and beautiful.

Amer Saleh Hagos Muhammad has given Eritrea—and the world—a gift. This is a book that deserves to be read, studied, and remembered. It is available in both e-reader and paperback formats.

Final Note:

A must-read for students of African liberation movements, postcolonial studies, and diaspora youth seeking to understand the sacrifices behind a flag. With its careful attention to archival justice and moral clarity, Echoes of Bravery is both a scholarly resource and a profoundly human story.

Awate Forum