Reviewing Negarit 320: A Letter of Truth and Reconciliation

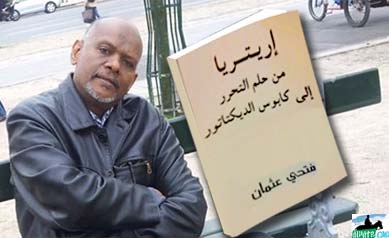

In Negarit 320 published April the 10th, 2025, Saleh Gadi Johar, henceforth referred to as The Writer. The latter because this article relied solely on the written text that was published at awate.com on April the 11th, 2025.

The Speakers starts the speech with a noble wish how he would’ve loved to feel pride and approbation in what was achieved under Isaias Afewerki’s leadership. At the same time the speaker laments about the irregularities in who gets priorities over others, although the people of Eritrea sacrificed across the board from all sectors of their society to the realization of independence.

From the admix of lament and the wish and the desire to have a leader that all Eritreans could be proud of, the speaker moves to what he envisioned Eritrea would be like under its first president. Capably, the speaker fuses what he envisioned Eritrea would be like to the speaker’s own childhood memories, namely the state-sponsored terror that induced untold trauma from the two successive occupations that Ethiopia exacted over Eritreans.

At the birth of the nascent nation, Eritrea, which the speaker witnessed firsthand, there were worrying signs that were ignored under the auspices that a nascent nation must face and commit errors as any new nation would. The worrying persistence of injustices, however, kept lurking in the Speaker’s conscious mind; the fact that the people had no say in how they were to be governed, with no signs of any institutions that must be built to allow for the rule of law to reign in – that puzzlement appeared to have stayed lurking within.

The language shifts back to the wish to feel pride. Only this time the speaker furnishes examples from world history where people were proud of “Fathers” of their respective nations. Through this shortcoming from the President, a reader can infer, thus subtly, that Isaias Afewerki has been in power for 34 years since independence and counting. Prior to that, too, it should be mentioned, Isaias Afewerki was a leader in the 30 years of revolutionary struggle for independence that culminated in 1991.

The speaker personalizes the message by saying, “you let me down, you let the nation down”. The speaker coyly uses the private citizen and the public intellectual, making the personal political and the political personal. Here the shifting of the speech occurs where the speaker elicits emotions of sadness, thus sympathy from readers, that he has malice toward none, not even the very president that he is directly addressing his speech to. There is no anger. Rather subdued and controlled demeanor. But then quickly, too, shows the shift about to occur in giving the counter narrative to acknowledge those who admire, adulate, and would give their life for the first president of Eritrea.

Indeed, the speaker takes his readers and viewers through a litany of verifiable adulations – from the familial to the spiritual to the social – that some people showed and continue to show since the independence of the nation in 1991. He touches the familial by spilling it out that some adulate Isaias more than their own parents. Some even compared him as the only religious figure who would outcompete him is Jesus. But The Speaker wasn’t going to only enshrine the man. Surely, he directly addresses the president by saying, ‘you’ve earned admirations the first few years of independence.’ The Speaker subtly reminds the President of the temporary nature of populism that would ebb and flow by events or wax and wane by the mood of the public.

The intoxicating nature of praises and adulations is no different than those who have the disposition of believers; no matter what, they feel protective of everything their leaders do, say, and not say. But that’s the fate of “strongmen” who end up feeding off the praises heaped on them; anything short of that becomes so contentious, the disappointment can be equally devastating to the entire population laced with polarization.

Now, The Speaker takes a serious tone as the subject matter goes beyond the individual leader and the dedicated supporters to the nascent nation barely 34 years old. Has the Father of the Nation met the expectations of all Eritreans? The Speaker left that question open for the Father to answer himself, allowing him to introspect, reflect, and wallow in the late stage of the Father’s life as a leader of a new nation who has been a dominant figure in the history of Eritrea, thirty years before and thirty-four years after independence. The Speaker quaintly, truthfully, and pragmatically leaves the 65 years of leadership to the man himself to address.

Respectfully, The Speaker hits hard on the stained record of the young leaving the country in droves, the fear factor that left every citizen vulnerable to the institution of random imprisonment, and many other unsavory practices of a nation that came to be as a result of countless sacrifices.

The Speaker, at the end, offers as a starting point to heal the people and the nation five salient points for the Father of the Nation to consider: (1) To drop any hint of filling the regret for Eritreans to return to their homeland; (2) to release the citizens who are incarcerated for no discernable reason; (3) to reign in on the vendetta-filled animosities with our neighbors. Even if it means “face-saving” for Ethiopia’s leader, it is a mark of leadership for peace’s sake; (4) Eritrea has seen more than its share of wars in the 34 years of its existence; preaching for peace is doable; (5) retool, repurpose, and repackage mass communication by sending messages of reconciliation, of peace, and tranquility.

As a writer, I have followed Saleh G. Johar since 1995. His activism has always been consistent in that he believed and still believes in genuine dialogue to a point when I think of reconciliation; he is the first person who comes to mind. Before the war of 1998, I remember it vividly when he offered the proverbial cloth to adorn the inevitable table at which Ethiopia and Eritrea will resolve their differences and sign an agreement of the cessation of hostilities between the warring nations. Sure enough, the war was concluded by negotiations.

Therefore, this open letter to the President of Eritrea comes at a crucial junction in the journey of our nation, where we are hearing we have arrived at the Safe Harbor (Barr-al-Aman). This is an ideal time for The Father of Reconciliation in Diaspora to address The First Father of a nascent nation in the homeland, for the nation belongs to all Eritreans.

Awate Forum