Book Review: The Burden of Exile

This is a review by Bereket Habte Selassie of the recently published book, “THE BURDEN OF EXILE” by Aaron Berhane.

I. The Heroic Pioneer

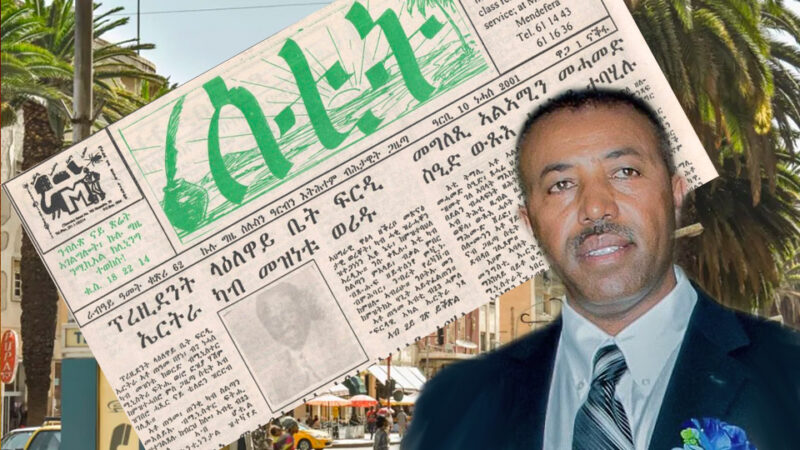

He had been an icon, at once inspired and inspiring. His friends and former collaborators never tired of singing his praise as a dedicated fighter for democracy and freedom of the Press. In the sad story of the dictatorial regime’s suppression of the Press and of all other constitutional rights, he ranks among the top heroic pioneers of Free Press, establishing the first privately owned newspaper known as Setit. His newspaper and others that followed suit had shaken the dictatorial government to its very foundation. In their new-found rights (and implied power and influence), the pioneers did not realize that their new private enterprise would constitute a serious threat to the dictatorship denying it a crucial source of power derived from its monopoly of the means of communication.

The Idea of a Newspaper Enterprise: Owning and Operating a Newspaper has been debated fiercely and tested with blood, sweat and tears. The outcome was suppression, clamping down of the heroic fight by a few courageous pioneers challenging the dictatorship and loudly and clearly asserting their God-given (and constitutionally guaranteed) right of free expression. It was all to no avail; the government abandoned all pretensions of allowing democratic rights and freedom of expression and prohibited all private ownership and operation of newspapers and other means of free expression of ideas. When the leaders of the newly created newspapers protested, the regime threw to the wind all pretensions, revealing its ugly teeth of steel

and imprisoned all the protesting leaders of the newly established newspapers, except Aaron Berhane owner of Setit. Aaron was given information by an insider informant of their decision to arrest him, a decision that he had instinctively understood as it was the nature of the dictatorship and its evil scheme. So, rather than risk the fate of loss of his freedom and even his life, he chose to run out of the country. But this decision to flee did not happen until the crucial and fateful event, September 11, 2001. For in the meantime, an extraordinary series of events were developing eventually reaching a point of resolution. The first was the explosion of the idea of a Free Press and its manifestation in the series of openings of some fifteen new newspapers between October 10, 1997, when a newspaper named Liela was created, and September 11, 2001 when the government, having waited with evident trepidation, finally decided “to cross the line,” as Aaron puts it.

The Final Confrontation

It cannot be overstressed that the dictatorial government in power has had the monopoly of power over all means of communication, including individual and public expressions of views or sentiments, a monopoly originated in the public support freely given to the Eritrean Liberation Peoples Liberation Front by the all-trusting and patriotic Eritrean public, a support necessitated by the demands of the liberation imperative. That historical imperative was required by the prevailing conditions and the meeting of minds of the people and the liberation forces.

There is no need to indulge in the discussion on the idea as to who should own the means of communication, and the origin of the tedious debate inevitably grounded in the dominant idea of the time, Marxism. All of that, including the validity or relevance of Marxism in situations such as ours needs to be understood as part of our history, whether we subscribe to it, at the moment or not. What is relevant now is how to evaluate the relevant issues concerning who has the right to own and operate means of communication. The government’s view is obviously that it must own and control of the Press and other related modes and means of communication. For it all boils down to power: the government would lose power unless it controls all means of communication.

But then an opposed idea of the right of members of the public to have ownership and operation of means of communications emerged as a historic necessity and members of the emerging educated elite, including prominent young former tegadelty began demanding that they should be allowed to own and operate Newspapers and allied means of communication.

Starting A Newspaper Business

In an interesting personal reflection, Aaron Berhane says the following:

“Like most young people, I was very ambitious. Eritrea had recently won its independence after a bloody thirty-year war with Ethiopia, and I wanted to play my part in restoring our culture, preserving our language, and keeping my country from repeating the mistake made by other African countries after they gained independence…” Aaron then cites the way the government

handled the protests of the ex-fighters. His excitement at the sight of the first issue of Setit when he went to the printing house to pick up the first issue illustrates the idealistic assumption of the pioneers that their excitement and enthusiasm would be shared by the government, or at least would not be resented by them. In the book under review, Aaron says:

“I saw a copy of Setit atop a bundle of two hundred papers. I beamed and plucked the top copy. I smelled the heady aroma of fresh newsprint and was thrilled at the notion that I was finally holding my newspaper in my hands. I turned the eight pages of the issue and saw that it was perfect, just as we dreamt…This was the starting point of the first independent newspaper in Eritrea. It opened a vital forum for public discussion. Gebray and I grinned from ear to ear. “ In the same paragraph, Aaron inserts a tone of fatal optimism by declaring: “That’s history and will never be rescinded. (p.47). This optimism would be met by the cold facts of a dictatorial regime’s decision of suppression of the Press and imprisonment of the pioneers of the Free Press, as we shall see.

II. Retrospective and Prognosis

In the following retrospective, we see the original motive that drove our pioneer journalist and freedom fighter to make the fateful decision to start his Newspaper publishing enterprise and the life-changing consequences of that decision, including his precipitous departure from home and undertaking a perilous journey ending in a life of exile.

Alas! It was not to be. While living in exile with his family, following his miraculous escape, and hoping that one day he would return to his beloved homeland and resume the interrupted patriotic project of publishing an independent newspaper thus becoming an integral part of the struggle for true freedom in our country, Aaron Berhane tragically met an untimely end. Tragically because he died as an exiled refugee fighting a deadly virus, a fateful sequel to miraculous escape years before, beating the dictator’s murderous agents who pursued him like a hunted animal, with the order of “shoot to kill.” The resourceful and indefatigable Aaron beat the odds by safely making it through a series of checkpoints and search by government agents and finally running for dear life like a Marathon athlete and escaped leaving the pursuing armed soldiers far behind and disappearing into the bush of the welcoming Sudanese territory.

Next to his safe escape from capture and settling in Canada, the safe escape of his family was his principal concern. Again, with the help of friends and well-wishers and the collaboration of international human right organizations, his family joined him in Canada in a joyful reunion with tearful celebration . After his family were reunited with him, Aaron began a new life with his wife Miliete Tseggai ( Mileat) and their three children. His younger brother, Amanuel, had also arrived two years earlier. His restless mind and undying hope of returning home one day induced in him a fierce determination to do his best to continue the struggle in different ways. At the same time, he couldn’t help pondering the vagaries of Fortune. Reviewing his life and especially his significant achievement of starting a newspaper publishing business, he was nonetheless assailed with sadness and some regrets especially remembering the fact of his departure from Asmara, his beloved home. He writes nostalgically thus: “I never thought or even dreamt I would leave my home city—Asmara. That was the city of my ancestors, the origin of my being. I have a strong attachment to this place, as if it belongs only to me. I built my family there, and I meant to raise my kids there. So, I assumed it was my duty to fight the corrupt system with my pen to assure fairness in the justice system, transparency in its government, accountability in the administration that hadn’t existed for ages. It was my love for my country that fired my heart—and drove me out of it. What irony!”

In his mind’s eye, he goes back to the time when he had written a letter to the government -owned newspaper and they did not publish his letter. They were having tea and snacks with his beloved wife, Milieat; noticing his furrowed countenance of worry, Mileat had said:

“Let me guess…they didn’t publish your letter.”

“This newspaper will never publish any dissenting opinion,” he answered her.

“What do you expect from a government-owned newspaper,” Mileat Said.” The government likes to be praised, not criticized. But you never give up,” she told him with her ever-encouraging confidence.

Evidently Aaron’s wife must be an equally perceptive observer as well as supportive of her husband’ aspirations. Following the brief exchange of their tea-time conversation, Aaron continues his reflections providing us with his insights and aspirations as follows:

“Like most young people, I was very ambitious. Eritrea had recently won its independence after a bloody thirty-year war with Ethiopia, and I wanted to play my part in restoring our culture, preserving our language, and keeping my country from repeating the mistakes made by other African countries after they gained independence.”

He then goes on to cite the example of the way the government had handled the protests of ex-fighters, who had organized demonstrations in protest and the government arrest of a few hundred of the protestors.

These events and especially the arrest of demonstrators seem to have triggered in Aaron’s mind a determination to continue the fight in one form or another.

“I have to own the media to write whatever I believe is right.,” he had declared in response to the government’s decision to imprison the demonstrators.

“That would be nice, “ Milieat said, adding, “But who will let you do that?”

Together with fellow freedom fighters, he had made a valiant attempt to make freedom a reality by daring to challenge the ruthless dictatorship opening the first private newspaper. It turned out that some of the arrested demonstrators had been sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. Some died from torture. The demonstrators had dared to take Isaias to the Stadium for “interrogation” on some burning issues, including the fact that he had ordered the ex-fighters to serve two more years without pay.

Aaron mused with bitterness that his two younger brothers had died with the hope of building a free and democratic Eritrea. He resolved to write letters to the government-owned newspaper, Hada Eritra, about issues that mattered to him and the majority of people. When they did not publish his letters, he made a solemn declaration that he had to own the media to write what he believed was right. It was a kind of personal engagement with destiny and when he made the declaration his wife was listening intently as if everything depended on it. Her sympathetic ear was a profound encouragement. When he finally declared, “I have to own a media to write whatever I wanted,” his wife said:

“That would be nice, but who would let you do it?”

And in his book he writes:

“She was right. Three years have passed since we attained our independence, but the government didn’t intend to introduce laws that would allow citizens to exercise their basic rights—freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, or freedom of peaceful demonstration. So, we had no choice but to wait.” Noting the fact that the government passed some proclamations on a number of issues, Aaron said that he was not sure that those laws were what the people wanted. What was needed was, he wrote, laws that allow them to express themselves what they needed without fear of repercussions as happened to the demonstrators.

Then the government published a new law in Eritrea’s Gazette, allowing citizens to publish a magazine or a newspaper. Aaron couldn’t wait to break out from the family meal they were having in his father’s large house. When lunch was over, he ran to the living room of the house, picked up Eritrea’s Gazette from the table and disappeared into the bedroom. He read the law meticulously; he found some of the provisions of the law ambiguous.

Miliete (or Mielat as he called her) entered the bedroom and throwing her arm across his chest told him his father was looking for him.

“This is exciting, Mielat,” he told her kissing her affectionately. “Read it and we will chat later. I have to go now,” he told her rushing out.

There is a touching scene in which Aaron was preparing to speak with his father about the exciting piece of news that would transform their lives and his young daughter, Freiweini (or Frieta as the family called her) who was recovering from illness was better said she wanted to paly Hide and Seek with her father. But he was in great hurry to talk to his father about the exciting piece of news and what they needed to do. What does a six-year old girl care about some exciting news! As soon as she saw him and her grandfather, she stopped riding her bike and ran toward them, kissed her father and hugged her grandfather affectionately.

Her father had touched her forehead and said, “You are getting better.”

She said, with the irresistible charm of a young child, “Yah, let’s play hide and seek.” It was a demand bordering on a command. Aaron said, “Okay, but can I eat my snack first?”

“No, let’s play first.” Aaron called her “the boss.” And did as she commanded with a father’s love and indulgence.

We will leave this touching scene of a charmed circle to continue the narrative.

Embarking On an Exciting Enterprise

Aaron found Mielat reading the Gazeete and asked her what she thought about it.

“I am not sure, Aaron, it is risky. If you publish articles like the ones you used to send to Hadas Eritra, they could throw you in jail. This Press Law will not protect us.”

Aaron left to hold a strategic meeting with his two putative partners, Gebray and Habtom.

As the primary founding person, he briefed his friends on the potential risks. They were intrigued and excited at the same time, according to Aaron’s account in the book under review. However, as a mark of their eagerness and enthusiasm, they were in favor of going ahead establishing the newspaper, despite their frustration in view of the “dysfunctional” administration of the government and how badly they ruled the country, like Aaron they too wanted to do something about it.

“How much money will we need,” Gebray asked.

Aaron replied that apart from knowing about the law provided under the proclamation, he did not know very much about the business and that they would need to do research on the subject. He then drew several sheets of paper from his bag and said that he had assigned a task for each one of them. He asked Habtom to find out how many printing houses there are in the city and obtain a quote for what it would cost to print an eight-page newspaper from each printing house. He asked Gebray to find out about the distribution network of Hadas Eritra: assigned each their respective tasks, he then placed a sheet of paper in front each of them.

Gebray picked up his paper and started to read.

Aaron said he would research Hadas Eritra, its circulation, how many copies were actually sold, its printing costs, and the human resources needed to produce a weekly newspaper, as well as the equipment needed to ger started. He also said he would conduct a random survey to learn what columns are popular and try to gauge how people truly feel about the paper.

Aaron observes proudly in his book that the strategy meeting that he led was very productive, stating that the founding partners agreed to go about their tasks quietly, “so as not to tip off too many people about their aspiration to launch the country’s first independent newspaper.” They parted full of excitement, and eager to start on their respective tasks.

Examining the initiative and energy that is required to launch such an important enterprise, it is not hard to reach a conclusion of the impressive skill and knowledge which these pioneers, and particularly the leading figure possessed to launch such a business. From what he gathered reading the book under review, it became abundantly clear to this reviewer that Aaron Berhane was endowed with the requisite skill and strength of character. It was also clear from reading parts the book that in addition to his inborn ability as well as the relevant knowledge acquired from institutions of a higher learning, he was also fortunate to have a father who has been a successful businessman in and around his village community of Gajiret and Asmara. This means that Aaron was raised in an environment that contributed to his business acumen and the necessary attitude toward business enterprises.

III. The Promise of Free Press and Its Challenges

In the closing paragraph of the preceding part of the book, we mentioned the nurturing environment that helped Aaron gain insight and ideas about business by virtue of the fact that he grew up in a nurturing family environment with the head of the family being an enterprising businessman. Reading the perilous adventure of the journey towards Sudan also shows other aspects of Aaron’s character. One example illustrating the suppleness and creativity of his mind was what happened at the last checkpoint how he fooled the armed military guards inspecting them near Girmayka. They stopped the car in what could be called in the middle of nowhere, not far from a place called Forto.

Their guide, Petros had warned them that the next checkpoint was the toughest one.

“They will ask to see our permits and reason for our trip,” Petros said.

“So, let us rehearse our answers again,” Aaron had recommended.

“Yes, but not only our answers but how to stay composed. There may be people there from the National Security who are trained to read every movement of your face.”

“That’s scary,” Gebray said. “At this time of the year most of them aren’t happy to be there.”

“Don’t worry too much” Petro said.

Aaron, who was driving the car, said the area was near the Sawa military training center.

He continues telling the account of their long journey.

“Only one of the soldiers was armed with an AK-47 rifle; he stood at the side of the car and placed his hand on the door handle. Both soldiers eyed us grimly and spoke tersely and authoritatively.”

“Menkesakesi, (permit), the soldier said, and leaned into the passenger side, menacing Gebray. He thrust his hand into the car and Gebray deposited his permit into the waiting palm. The soldier inspected the document closely, rubbing the pages between his fingers to test its authenticity.

“So what brought you here?”

“My sister. She lives in Girmayka,” said Gebray.

“How long are you going to stay?”

“Just two days. I’ll be back after the holiday,” Gbray said woodenly as if reciting from a script. Before the soldier could ask any further questions, Petros offered his ID and told his story. He was coming to visit his brother who was at Saw military training center. On the way he would buy butter and firewood for the wedding of his other brother from Girmayka…

“When will you be back?”

“Tomorrow.”

The soldier kept staring at the papers, which he kept toying with, in his hand. He seemed to have run out of questions but didn’t wat to let them go just yet. They all felt uneasy and wondered what he was waiting for.

“By the way, is Wedi Haile around”? Aaron asked in an attempt to distract the soldier.

“No, he left last week to celebrate Christmas with his family,” the soldier said.

“Lucky boy, please extend my greetings. My name is Samuel.”

“Sure, I will.” The soldier said and returned to his companion ordering him to lift the bar as he returned Petors’s and Gebray’ documents.

“Have a great evening, “ Aaron said. The soldier waived his hand…

Wow, We made it!” Aaron cried laughing loudly, and went driving toward Girmayka.

“ Who is Wedi Haile?” Petros asked.

“I have no idea,” Aaron said, laughing.

“What if Wedi Haile was around and he called him.” Petros asked.

“Well, I would have said, the other Wedi Haile.”

Both he and Gebray layghed hysterically.

Of such as these are creative minds composed!

We have seen Aaron at work creatively inventing stories and amazingly helping clear the way to success in that hazardous journey filled with pitfalls in numerous twists and turns. What miraculous deeds of national import might he have been accomplished had he and his partners been allowed to apply their minds and spirit in that rudely interrupted enterprise that was full of promise.

What about the other two partners, what motivated them?

We know that one of them is a talented cartoonist. Such natural gift, properly nurtured, might have been the source of growth intellectually or professionally once the foundation was firmly grounded. Not much is said about Habtom’s family background or his intellectual endowment to qualify him as a strong member of the triad. One thing common to all three partners, which is critical in creating bonds and special friendship was their dedication to the patriotic aim of making their country a place in which the ideal of democracy and justice had been part of their life during the national struggle for independence. In Aaron’s case, he spent much of his youth in the liberated area of Sahel under the wings of the liberation Front (the EPLF). His advent to Sahel was caused fortuitously by the fact of his father’s open support of the EPLF and as such had been a target of enemy hostile attention. In fact, he was forced to flee to Sahel for fear of being arrested and it is known that he took his young son with him.

Aaron was 22 years old when Eritrea became independent in 1991. In other words, old enough to have experienced some of the negative sides of the Sahel syndrome, including the discouragement of religious belief, at least in the earlier part of the liberation experience. Let us recite one of his reasons why owning a private newspaper is a worthy objective. We italicized and put it in bold mark. Aaron said he wanted to play his part in restoring our culture. It is impossible not to speculate that Aaron might have had some serious questions about the anti-religious and anti- individual freedom that was implicit in the guiding EPLF ideology that also discouraged the traditional respect for elders as “backward, feudal sentiment.” So, the “restoration of our culture” that Aaron hoped to see realized was a worthy objective acceptable to the majority of our people. Indeed, the entire experience of the liberation struggle, though right as an objective, left much room to be desired when compared to the golden mean of our age-old traditional culture with its noble values that had been either neglected or deliberately discouraged during the struggle.

The Birth of Setit

Setit, the first independent Eritrean newspaper, was born. It was named after the only river in Eritrea, as Aaron explains, “…since we wanted our newspaper to flow unimpeded, like a river.”

The partners prepared about four months of articles in advance. They wrote at night and tried to sell advertisements during the day. They worked this way for months before most of their friends knew what they were doing. When Mielat asked her husband when they were planning to print the first issue, and he asked her what she suggested, she suggested May 24, 1997, Independence Day. So, on August 21, 1997, the first issue of Setit was printed. Aaron and Gebray went to the Adulis printing house and picked up a bundle of the first independent newspaper in the country.

There is also an important historical event that occurred around the same time, namely the approval of the Eritrean Constitution, signed by the National Assembly as well as by a Constituent Assembly of elected representatives. Indeed, even though the constitution remained unimplemented, one can easily imagine the encouragement given to these pioneers by the signing of that historic document and its potent power as the source of the ideals for which our heroic pioneers labored and risked their liberty and life in order to accomplish those deals. The ratified constitution is a prisoner like some of the historic leaders whom the dictator locked up in the desert where they have been wasting for over twenty years.

IV. Setit, Symbol of Future Free Press

The legacy of Setit and the other private newspapers of Eritrea represents the universal contest between Freedom and Oppression, or in terms of the larger historical history of humankind, Freedom versus Slavery.

As a matter of historical record, we owe it to the other newspapers to name them as recorded in the book under review. They are listed in the book in the order of the appearance as follows:

- Setit, August 21, 1997

- Liela, October 1997

- Tsigenay, November 1997

- Mestiat, Novemenr 30, 1997

- Wintana, March 1998

- Kestedebena, November 1998

- MekaliH, December 1998

- KeiH BaHri, January 30, 1998

- Zemen, February 21, 1998

- Asmara Lomi, March 21, 1998

- Admas, May1, 1998

- Ma’Ebel, July 1 , 1998

- Adal , July 14, 1998

- Selam, September 3, 1998

- Timnit, September 3, 1998

- Millennium, October6, 1998.

From the time of the appearance of Setit in August 21, 1997, to Millennium’s October 6 appearance, is one year and two weeks, representing an extraordinary explosion of creativity also marking a sign of hope and optimism in our people. It is reasonable to assume again that the promulgation of the Constitution did provide a ground for hope and optimism. It is equally reasonable to assume that many, if not all, of the people who started these private newspapers would have recorded their experience both of excitement first, and then of bitter disappointment. As a premier pioneer, Aaron Berhane excels in much of what has been done by him ultimately leading to the writing of his book. One hopes that the other pioneers of the newspapers listed above would be thinking of doing something similar for leaving their intellectual and spiritual footprints to posterity.

In the last chapter of this incredible book, Aaron speaks of his advent to Toronto, to which he eventually moved from Regina and met with some friends and relatives. He relates the story of his cousin Yordanos whom he admires immensely for her courage and resilience. In this chapter as in much of his writing, Aaron demonstrates an important quality of resilience, which is crucial for survival and coping with problems. The story of Yordanos illustrates what kind of challenges all refugees face and how they meet the challenges.

The Final Confrontation

Aaron states that the four-year period of the life of Setit (1997-2001) was difficult. He writes:

“We attempted to exert pressure on the government to implement the constitution, fight corrupt generals, focus on education, improve healthcare, and review the land and investment policy. Inevitably, the government was not happy with the content of the newspapers writing that was critical of the government. Intimidation and threatening phone calls followed. Nevertheless, the newspaper continued publishing. It published stories about the arrest of two thousand university students for refusing to sign up for a compulsory work program set up by the government….We became the voice of the people by echoing their pain and concerns.

The tipping point came on June 5, 2001, when Setit published an open letter by fifteen senior government officials known as “the G-15” criticizing the president and calling for democratic reforms. Immediately, the intimidation and harassment intended to block the free press escalated.

Aaron continues:

“(The country was not at war at the time.) The Tactics were symptomatic of a paranoid government, but the government did not fully cross the line until September 11, 2001.

The Fateful Decision

On Tuesday, September 18, 2001, one week after the terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon in Washington D.C., at 7 a.am. the news came over the radio that, effective immediately, the Eritrean government had ordered all private presses to cease publication.

Aaron notes at the beginning of chapter four of the book under review:

“I was in bed with Mielat when we heard the words of the presenter on Radion Dimtsi Hafash, the government station.”

“They are shutting our newspaper. I can’t believe this,” Mielat cried.

“The pretext given by the government for their decision was that we had broken the law by failing to pay taxes.

“This is a total lie,” Mielat had said to which Aaron (probably laughing) said, “I know.”

EPILOGUE

While reading this book principally focusing on key events and issues, I also learned about the wonderful story of family life and its human side involving the usual seesaw of stress and strain as well as joyful occasions at the individual as well as at the collective level. By and large the main story about the loving husband and father, Aaron Berhane family with his wife and children, was a typical happy family story in all respects until the cruel decision of what Aaron called a regime headed by a paranoid president completely changed their life. A promising start of an independent newspaper enterprise, typified by the one named Setit was nipped in the bud when it was just making incredible progress and exciting the reading public that was given a foretaste of a future of democratic possibility—of a system and society. Coincidentally, at the time when the exciting adventure of an emerging free Press, the Eritrean nation was engaged in a historic process of constitution making in which I was privileged to have played a part as chairman of the Constitutional Commission that drafted the constitution.

It was an altogether exciting time full of promise. The inauguration of the first independent newspaper with the name of Setit, showing the way. It was a wonderful experience for the pioneers of the first independent newspaper, their friends and family. Reading the book under review has enabled me to be virtually part of the life of the principal actors of this drama—the pioneers, their families, and friends. It has been a privilege, at once ennobling and humbling.

One important detail that I must mention is that the Afterword of the book, titled “The Invisible Enemy” was written by Freweini (Frieta) Berhane, daughter and oldest child of Aaron Berhane. I had met Friet virtually when reading the book; she was a delightful and playful child of seven or eight when Aaron left his beloved family and city in 2001. The Afterword is a very well written chapter, written because Aaron passed away before writing the concluding part of the book. Another important detail related to Aaron’s family is his wife Miliete, a soft-spoken and by all accounts a beautiful woman both physically and spiritually. According to the description of her husband, Miliete ranks at the top as an angel, devoted and loving. Their love in all respects was exemplary and enviable, a love that stood the test of time and the cruel fate of exile. Miliete’s graceful and courageous acceptance of her husband’s untimely and tragic death, judging by the accounts of friendly observers, approximates to the definition of inimitable courage–grace under pressure.

As for the dearly departed father of the family, his daughter’s description of him is that he is perfect. She wrote in the Afterword thus:

“My father was the most courageous, brave, insightful, caring, kind, resilient, and charismatic person I have known.” (Page 270).

I hope to meet this wonderful family in the not-too-distant future, Insha’Allah!

Awate Forum