Politics of Nouns And Topography

I had ruled out Medrekh as another Keremtawai mae’etot until I heard Qeisi’s interview with Amal Ali. I liked what he said; particularly his emphasis that the legacy of the struggle belongs to all Eritreans. His tone was right and proper. There was only one important question that he avoided: the move to revive the EPLF exclusively. Ironically Medrekh’s views on that seemed to contradict his assertion that the legacy of the struggle belongs to all Eritreans and not only to those who were affiliated with the EPLF. In spite of that, I liked his tone and most of what he said. I wish his colleagues were taking notes on how to communicate with the public.

I had also wanted to write about the intensive and orchestrated defamation campaign that was waged against me in the last five-years concerning the “Ali Salim is Saleh Gadi” saga. I would have liked to address it promptly, but a friend has advised of an alternative approach that would put the issue to rest and I owe him the benefit of the doubt. I hope he is right; if not I will come back to address it soon. This edition of Negarit will focus mainly on the hot topic of the month, the so-called “Eritrean Lowlanders League (ELL)” and the controversial debate it has ignited. Those who do not read Arabic might not appreciate the significance and scope of the debate; the few English materials posted on awate merely touched the surface.

The People Behind The Seminar

On March 29, 2014, a group of Eritreans who hail from the “Lowlands” gathered in London and launched a movement they called ELL. Seven founders signed the document; I know them all: Taha Yacob and Saleh Moh’d Omer were my classmates and Mahmoud Aderob was a schoolmate, who lived in my neighborhood, during high-school. Both Aderob and I joined the ELF and today both of us have ended up in the USA. Ustaz Mahmoud Ibrahim, who used to write regularly for awate.com, and Hamid Omer Izaz are people I consider friends. I have known Mohammed IsHaq for the last five or six years through a paltalk room he runs out of Sweden. I have known Ismael Adem since 2000 when I permanently settled in the USA. I am sure many readers know him: he is the young man whom Isaias mocked and scolded in the 1993 Washington, DC public meeting simply because he asked about the status of the Arabic language in Eritrea. I met Gemal twice–once in Germany and again in Awasa. I also know most of the attendees, for example, both Ms. Aisha Gaas and Dr. Mohammed Kher are good friends.

I mention the names above to underscore the strong ties I have with each and every one of them, but more importantly, to state without any equivocation that they are all my allies in the struggle against the unjust PFDJ regime. Naturally, I neither appreciate nor approve the way some people have gone beyond criticizing their agenda and meeting, to question their credentials; it is wrong to doubt their patriotism. Yet, I believe they are wrong on this one. The core issues and grievances they have raised have been the reason of my activism for almost two decades. I just object to the way they decided to go about it.

The above introduction is my way of appealing to everyone to understand the spirit in which I write this article: to disagree with my friends without being disagreeable. Our differing positions should not be allowed to interfere in our personal relations; that is how I addressed the Medrek group in the last edition of Negarit. Incidentally, I consider both movements equally wrong on their approach and not on their issues. I will start with Medrekh. But first, let me share with you a few funny lines I have read lately.

An Abuse of Rights

Writing about “the right of Eritreans to organize and struggle in any way they see fit”, someone wrote: you have the right to jump off the tenth floor, but it doesn’t mean you have to do it!

Some may argue (already a few are) that Eritreans have the right to organize and associate in the manner they see fit! That is true, no argument here. But at the same time it is a laughable argument—it is simply stating the obvious. Forcefully stating that the sky is blue would only summon a chuckle. Everybody knows the sky is blue, just like everybody knows people have rights. So why such a patronizing argument! What is controversial about the right of people to hold a seminar and create an association? Nothing at all.

Loudly stating such universally accepted values doesn’t make a person any wiser or more of a democrat. Rights are sacrosanct; they are, however, not a license to do whatever one wishes. People still have to operate under the dictates of reason, law, religion, tradition and history. One could say that people have the right to go naked on the streets, but we don’t see many people walking stark naked simply because they have the right to do so! I know some people who drink liquor, and stating a boring fact, they have every right to drink or abstain. But a few advocates of absolute, unfettered rights, among the defenders of the ELL, will think ten times before they hold a bottle in public. Rights are not practiced in a vacuum. If practicing the right of someone infringes on the rights of another, even if on the emotional level, by crossing the limits of decency, again stating the obvious, it is a transgression. The transgression weighs more on the value system of human beings; not the selfish who may supposedly exercise their individual rights.

If I recognize the right of the ELL to organize, then, what is my objection?

Three Nouns: Medrekh. Munteda. Forum.

It is a sad reality that Eritrean political culture gives more weight to symbolism of diversity than its meaningful reflection. We can no longer afford to ignore that diversity means all people and all issues are on the national table; nobody and no issue must be excluded. No more empty slogans and gestures. I get irritated when I read “May Allah/God bless you.” Christians and Muslims have one God and as long as one is using English, there is no need to say Allah or Igzabier. It sounds as if we have two creators each competing for a constituency.

Apparently Medrekh has found an opportunity which has unfortunately came to blind them. No doubt they have secured considerable funding (they have been vocal about it), but they have regrettably chosen to continue working on the same path that brought us to our current sorry political reality. Medrekh has decided to reform the PFDJ instead of helping provide a non-partisan and an all-inclusive platform against the unjust regime. The mere use of the Arabic version of Medrekh doesn’t represent inclusiveness. What is disheartening is that their view of Eritrean unity is not much different from that of the PFDJ: nominal representation of affected segments—a failed formula of appeasing constituents by plugging in a few people who belong to certain constituencies.

Another concern is that some of them haven’t come to terms with the issues of refugees (particularly those who have been in Sudanese camps for decades), culture, devolution of power and land rights; they think these are partisan issues belonging to the ELF. I believe this is a recipe for a quick suicide. These kind of injustices are the very reasons that have inspired opposition to the PFDJ regime in independent Eritrea. The realization of justice, dignity and rights should have been a fait accompli in independent Eritrea; Eritreans deserve to enjoy them after a three-decade long arduous struggle. We have learned one important lesson from the merry-go-round of the last 14 years: changing the face of PFDJ is not a solution; it is a lethal continuation of the prevailing injustice. Besides, nobody is buying this all-too-familiar strategy anymore.

Medrekh is an exclusionary movement stuck in the past. What is needed now is politics that narrows the gaps among Eritreans. Instead of capitalizing on the opportunity to heal the wounds of the many hurting compatriots, they chose to continue in a way that deepens the already entrenched suspicions and mistrust. Still, I hope they will come to their senses, revise their practice, scrape away their initial launch rhetoric, discard their arrogant posturing and attitude, and think along a wider national parameters. There is always time for partisan politics, but now is not the time. Once we succeed in establishing the rule of law without the patronizing attitude of the PFDJ, where every Eritrean doesn’t feel ostracized, excluded or marginalized, we will have plenty of time to practice partisan politics. I still hope this will happen; because hope is the most effective tool at our disposal.

Geography without Demography

We still have people who prefer to bury their heads in the sand, just like the proverbial ostrich. We cannot pretend that the scent of spring is blowing all over the place and Eritreans are warm with each other. There are a few of us who have become whistle-blowers, and we pay dearly for that. But no turning back.

Every season, the Eritrean landscape needs a political Kamikaze who pays dearly for exposing some mischief, deceit, or looming danger facing the already sick Eritrean body politic. No Eritrean should be kept in the dark, or be systematically blindfolded by the mischief of ambitious politicians, and deceived by egoists and partisan rivalries.

For almost two decades now, I have been writing about social grievances. I endorsed the plight of the Kunama when it was still not only a taboo, but a blasphemy in Eritrean politics. I have consistently advocated for the right of refugees to return to their ancestral lands and against cultural hegemony when many of those who are raising the issue now were limited to teashop discussions. Of course, there are many other Eritrean issues, grievances related to, for example, the persecution of religious minorities; the Afar Eritreans who have become strangers in their own land; the Kunama and Nara who are watching their lands appropriated by the regime. The plight of the last two are not conventionally accentuated in the Lowland/Highland political discourse.

There are also rights that are rarely mentioned, for example, inhabitants of Sembel, and Megarih, who have lost their land to hard-currency paying diaspora Eritreans; The plains of Shimejana, Aala, Tsellema, Sabur, Mrrara, Solomuna…and many places in the Highlands that were grabbed by the government and turned into army agricultural projects.The lands around major sources of water are now military camps, including tens of camps, bases for different armed opposition groups from the region, mainly Ethiopians, that are installed on land appropriated from villagers in the Eritrean countryside.

Dankalia suffers the most since it is a dry region with a limited number of watering places, now mostly taken over by the army. Still, the army competes with the poor fishermen for the bounties of the sea by deploying modern equipment that the people cannot afford. The fertile areas of Barka which used to be grazing lands for the pastoralists has been turned into huge army camps—Sawa is located on a traditional grazing land. The herders cannot roam around in their traditional grazing lands since the Ethiopia-Eritrean border is insecure. The lands they owned are now turned into mechanized farms owned by the army–the land of Ad Omer is a perfect example among dozens of such injustices befalling the inhabitants of the region.

During their occupation of Eritrea, the Italians had confiscated all the fertile areas in the highlands. When citizens protested against that and rebelled, they were run over by Italian cavalry and killed. The Italians called all the land they confiscated “Terra Domaniale.” In Barka, concessions like Tekreret and Ali Ghidir were established at the expense of the real owners of the land. Today it is worse, every plot of land in Eritrea is taken by force, with no compensation, and owned by the government. The Eritrean government pursued the same colonial policies and confiscated more lands depriving the people of a dignified livelihood. Sadly, the whole of Eritrea is suffering though the history, length, and scope of the suffering in different regions may vary.

These Eritrean issues have always been my issues and will continue to be. Such major national issues should be our top priorities. But since I am addressing the founders of the ELL, I will limit myself to the main grievances that they’ve raised.

At the heart of Eritrean problems is the absence of justice and rule of law. At the heart of the Eritrean segment that inhabits the lowlands and other nationalist Eritreans are four main issues: 1) land 2) refugees 3) culture/language, and 4) power, resources sharing and development. I believe these are real issues that need to be addressed openly. However, I do not see these as exclusively “Lowland” issues; they are the heart and soul of Eritrean politics.

What’s In A Background?

My psychological make-up is that of a typical Kerenite. What makes Eritreans happy makes me happy; and what saddens them saddens me. I grew up feeling proud and admiring the pioneers of the struggle who confronted a giant enemy equipped with an iron will, unwavering resolve, and dedication. Like the overwhelming majority of Eritrean, I revere those who followed the footsteps of Hamid Idris Awate, the Eritrean hero, who declared to the first wave of combatants who joined him: “if there are any among you who came to benefit their region, their clan, or for personal vendetta, you must drop your guns and leave; we are in this for the freedom and unity of Eritrea.”

Long before Awate, another icon, the Eritrean hero Ibrahim Sultan, emancipated the serfs of the Eritrean Lowland (known as Tigre) before embarking on the long journey pursuing a vision to establish a free Eritrea. He resisted enticing offers from the powers of the day rejecting the partition of Eritrea. He rejected the cajoling of Haile Sellassie, and instead connected with other heroes, the first Martyr, Abdulkadir Kebire and the visionary Ras Tessema Asberom, and the great writer and politician Weldeab Weldemariam. Those great men established the Independence Block, the precursor to Mohammed Saed Naud’s Haraka that was followed by Awate’s defiant struggle to free Eritreans and to realize an independent Eritrea. In a nutshell, these men laid the landmarks for the Eritrea that we all jealously guard and adore.

Historically, despite some lethal and sad experiences during the formative years of the struggle, in general, politicians from the “Lowlands” have never been myopic, exclusionary, or narrow nationalists. They always had their eyes on the whole of Eritrea and always believed that the fate of all Eritreans was one: inseparable. They recognized the meaning of a true unity. If they didn’t, they wouldn’t have let Christians Highlanders to join them. The covenant among all Eritreans was that Eritrea is for Eritreans: “one and indivisible with justice and liberty for all.” What ails one segment of Eritrea ails all. The commitment to “One Eritrea” is why so many heroes in our long struggle, from Adal through Nakfa to Asmara, gave up their lives and we have the responsibility, inadvertently or not, to not undermine our national unity and what makes us Eritreans. We have fallen short on our aspirations; but two wrongs don’t make it right.

I believe that the grievances and the demands of ELL are genuine and national in nature. Therefore, they should be addressed and resolved in a national platform. And Eritreans have been struggling to create that national platform denied to them by the illegitimate regime ruling Eritrea. Leaving what Mao, Stalin, Lenin or anyone else said about self-determination aside, all Eritreans bear the responsibility of addressing and resolving the grievances of any component of the society. Ignoring the grievances of others, because it doesn’t hit home, is unpatriotic, irresponsible and is a call for social strife.

Anyone who is not interested in the agonies of his compatriots should stop deafening us with slogans of “national unity”! In this aspect, the chauvinism of a few Kebessa elite and their attitudes, acting like lords who are divinely mandated to control everything, is very annoying. Unfortunately, a large number of Eritreans liberals, be it from Kebessa or the Lowlands, are lost in the noise that the few chauvinists make. But things are improving, the situation now is much better than it used to be. But still a lot of improvement of attitude is required. That is why I don’t welcome any move that even remotely emboldens the latent counter chauvinism from the Lowlands.

On the Lowland side, I know many who hardly pass a day without mentioning the “Habesh” derisively, or accusing the Highlanders of being partners with Isaias. Yet, they hint at similar threats, remembering primordial cross border relations, not to emphasize cooperation and stability, but to scare, or to reciprocate their suspicion of the myth of the “Habesh” project. Obviously one should expect a reaction to the high pitched Habesha-centric noise that we came to notice over the last two years or so. And some are countering the challenge by stating: if some “Habesh” elements openly express their longing for Ethiopia at our expenses, we might as well threaten them with our extension in Eastern Sudan. The chauvinist Highlanders seem to get offended by this; the chauvinist Lowlanders feel vindicated. Both are reckless and they deserve each other. But those in the middle, the overwhelming majority and those who consider themselves liberals, should not miss the prize: the emancipation of all Eritrean from the yoke of the PFDJ or its resemblance.

Join the Political Organizations

The ELL ignored the fact that there are several opposition political organizations, some entirely made up of Lowlanders. There are about five Islamist organizations and many others whose members feel proud for having agreed among themselves on negligible points. That is why most organizations have become a laboratory for testing vertical and horizontal splits. The fact that they are not fighting each other has become their standard for success and achievements.

Given the fact that the opposition has failed to provide collective leadership, people are confused and in disarray. Even the ENCDC which was supposed to be a collective political platform became a jamboree of people who want to massage their egos in their spare time, or when they retire, or when they get a leave from work. The Diaspora has become more delusional, thinking it can run Eritrean politics from the West, on part time basis. They think of Eritreans in Eritrea, or the refugees (the major stakeholders) as mere militia forces waiting to be bossed around. I believe the ELL would be justified in organizing if its goals were framed as strictly national issues, not as regional issues. This is simply because such was always the legacy of the Lowlands. It is the legacy of Hamid Idris Awate and his companions whose last breath was the name Eritrea.

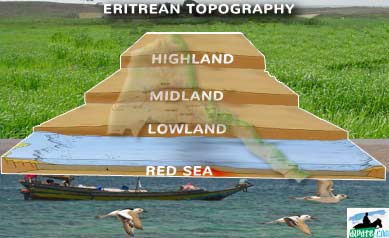

As it is, I feel my friends are selling the legacy and experience of the steadfast people of the Lowland very cheaply. A cause of a people that owns a history, of being the vanguards of the struggle and its abode, should not be packaged piecemeal, and discounted to a regional demand. All of Eritrea is Lowlands in spirit by the virtue of its role in pioneering and nurturing the struggle that led to Eritrea’s independence in 1991. And what is Sahel, by the way? Is it Lowland or Highland? Are the economic interest of Semhar and Barka intertwined outside the parameters of the nation state? How about Senhit? How do you distribute the “nationality” to the people of the Lowlands? Can one define geographical Lowlands without defining demographic Lowlands? The initiative invokes more questions than answers.

For now, I will go by the wisdom of a humorous friend: Keren is neither Highland nor Lowland; it is Midland! What a framing!

Barka is mainly known for its pastoralist lifestyle, the Gash is a combination of pastoral and sedentary economy. While Semhar is a different ballgame. Historically, Semhar mainly depended on its commercial and port-city economy, Massawa–the most liberal, diverse and cosmopolitan Eritrean city. Historically, the Abyssinians have always been the customers of Massawa, Dekheno, and several other smaller ports. Even during the Egyptian period when Munzinger ruled the area that was known as Taka, extending from Kasala to Massawa, Semhar has been the main gateway of the Abyssinians, let alone the Eritrean Highlands. One cannot underestimate or undermine this vital economic tie. Incidentally, the old ELF’s failure to recognize this vital fact resulted in the bloody splits and the creation of the PLF under the patronage of Sabbe. The alliance of Isaias and the Obel group with the forces of Semhar in the early seventies was simply an alliance of convenience, solely a military alliance that immediately collapsed—more so in post-independence Eritrea. It was not meant to last for too long. But the main fault line during the struggle era was the Barka-Semhar one.

For centuries, northwestern Semhar has been a grazing land (and farming) for several groups from Akele Guzai and Hamassen. On the other side of the southwestern escarpment of the Highland, Dembelass, is a lowland, a gulf connected to Barka Laal, across from Kerekon. Yet, politically, it is not considered part of the lowlands. During the formation of Eritrea, there was no distinction between Barka Laal and Seraye. The two were administered as one unit under an Italian governor, Pollera.

In short, the ELL reduced vital national issues to the equivalent of a demand of a minority group. How could people who comprise more than a third of Eritreans act as if they are a helpless minority? How could they short-sell their issues as a regional issue when it deserves to be on top of the national agenda, with distinction? How could people from a region that incubated, hatched and sustained the struggle for decades act so meekly? How could they reduce the issue and put it on the same pedestal as a single farmer demanding the return of his stolen cows? That is the core of my disappointment. But my disappointment with the repercussions of the move, the reactions of some chauvinists who were dormant, are even more. Some are considering the document a license to go wild on their sectarian rhetoric. They feel emboldened.

The initiators of the ELL never indicated their wish to sever the ties between Highland and Lowland Eritrea. But the way it was framed, and the noise that followed their initiative as a political issue, as opposed to an issue of justice, made it appear so.

Finally, I object to framing national issues as regional issues. I object to framing issues of justice for which Eritrean must struggle to rectify, as a tool of political posturing. I hope they reframe their initiative as a national platform that all genuine Eritrean nationalists can address in unison. But since they threw the document to the public, apparently without a thorough study on its repercussions and the potential damage it will inflict on the struggle, I encourage them to join the organizations that represent their aspirations. That way they can inject some vitality in the ailing political organizations.

This has been my observations and unsolicited consultations; patting the initiators on the back is not an advice.

Awate Forum