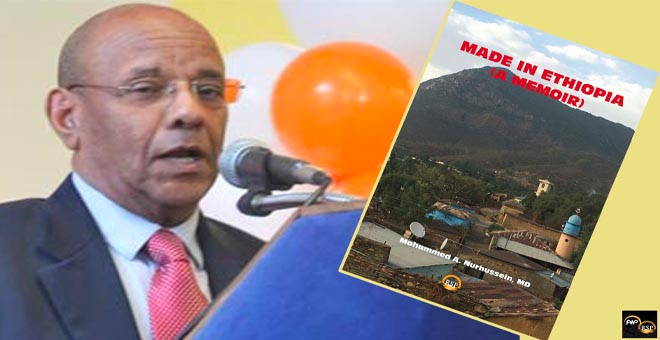

“Made In Ethiopia”: Review by Semere T Habtermariam

Book Review By Semere Tesfamicael Habtemariam

Title: Made In Ethiopia

Author: Dr. Mohammed A Nurhussien (MD)

Publisher: Red Sea Press

Year: 2020

Pages: 300

In his book, “The Constant Outsider,” Thomas M. Cirignano has written that, “Each of us is a book waiting to be written, and that book, if written, results in a person explained.” Made in Ethiopia is a book about Mohammed A. Nurhussien; it is his life story; it is his memoir. I am not quite sure how much the book explains his personhood, but when I talked to him, for the first time after reading his book, there was a sense of deja vu; a weird feeling that I was talking to somebody I had known all along. No doubt, he is very cosmopolitan, urbane and sauve, but beneath that veneer of sophistication is also that quintessentially Tigrayan character of modesty and politeness. I have always liked Tigrayans; in fact, I have never met a Tigrayan I didn’t like, and Mohammed Alamin Nurhussien was no exception.

Made in Ethiopia is the odyssey of the frail little boy from his humble beginning in Adwa to the academic halls and hospitals of Europe, Ethiopia and America. Although Mohammed pursued his education and training with unrivalled grit, determination and hard work and his singular goal was to return home and serve the people he loves, the rapidly deteriorating situation in Derg-controlled Ethiopia compelled him to grudgingly settle, work and live in the Big Apple. The emotional and psychological ordeal was hard to bear, but the presence of his beautiful wife by his side, the late Zahra, made all the difference.

Mohammed Alamin was named after the prophet and like him he had the misfortune of growing up without his father. Due to the economic hardships his widowed mother faced, he had to be sent away to Gonder. Mohammed loved his mother, w/o Teberih Yesuf; he was very close to her, and she even loved him more, but the physical gulf that separated them rendered it indistinguishable from the loss of his father. The loss of his father and the separation from his mother made him a true orphan. It was not only in name that he was like the prophet; both had experienced the gnawing pains of loss and loneliness. No wonder, Prophet Mohammed made the protection of orphans and widows one of the central tenets of his message. Perhaps, Mohamed Nurhussien’s interest in charitable work might have been influenced and rooted in his early experiences in Adwa and Gonder.

Many years later, the person who came to fill the gaping hole in his heart, was the virtuous Zahra. She was his Kedejah, and like her, she became everything to him. She gave him and his three children a life abundant with love and generosity that most people could only dream of. She was truly the crown on his head and the rock that kept the family together. Although she was called Home too soon at the age of 52, the way she lived her life with relish, sharing her blessings with family, friends and even strangers is a testimony to her faith and good upbringing. Her life was only matched by the way she died. Many centuries ago, the French Renaissance philosopher, Michael de Montaigne, wrote that “to study philosophy is nothing but to prepare one’s self to die.” Zahra was evidently quite a student. Her equanimity and calmness in the face of her debilitating illness and imminent death evokes the patience of Job: sabr ayub.

Although the loss of the two women, Tebrih and Zahra, whom he loved greatly was hard to cope with, the success of his three children and their abiding love keeps him going. And today, true to the adage that life begins at 65 in America, he is keeping himself busy through so many engagements in charitable and Human Rights organizations. Time has also given him the opportunity to reflect on his life and devote more time to the life of intellect. He is working on his second book on his involvement with Human Rights issues.

In some way, Mohamed’s story is the typical story of a hyphenated-American, an immigrant tributary that replenishes the river known as the American Dream. It is what sustains the American ethos and Mohammed can serve as its Exhibit A. One must be careful though to not let the familiarity and the evident personal and professional success of the author get in the way, for the book gently subpoenas each and everyone of us, particularly Ethiopians and Eritreans, to the court of morality, where we have to adjudicate our common humanity. What is the virtue of morality if we are only to speak against injustice when it only happens to us?

In his book, “Emperor Haile Selassie,” the Eritrean scholar, Dr. Bereket Habte Selassie, a friend of Dr. Mohammed who also wrote the Forward to the book, raises the question. “Does it [Iassu’s vision] contain within it the possibility of reimagining a history in which Christians and Muslim citizens would be made to feel equally secure…? This is a serious question that all thoughtful citizens of Ethiopia [and Eritrea] should reflect upon. To that end, the history of the Iassu-Tafari feud provides useful lessons.”

Modern Ethiopian history is written from the perspective of Christian-based ethnonationalistic perspective. This approach is not only wrong but evil because it tries to undermine, or even worse, justify the wrongs perpetrated against Muslim Ethiopians. There is a need for all of us to understand the complexity of the past with all it gories and cruelties. Christians could still celebrate their heritage while making the ugly truth of the past known. The uncritical acceptance of past heritage is not the best way to show pride and love for it. The truth, as the Bible says, shall set us free. The hurt that one feels from confronting one’s truth is temporary but its liberating effect endures.

Mohamed A. Nurhausien has told us his truth, his story, and I hope we are worthy of it. Giving up the right to reflect upon our past and the duty to remedy its mistakes is to surrender to prejudice and ignorance. Nothing is more demeaning than the constant feeling that one doesn’t belong in one’s own country.

Ironically Mohammed was born in Adwa, the once small trading city with a population of 15,000 in 1894, which has morphed to become the pride of Ethiopia and Africa. Adwa was the scene of the 1896 battle where Ethiopians, through sheer courage and unparalleled love of the Father-land, fought and defeated the invading Italian army. One would think that being indigenous to Adwa would make an Ethiopian feel to be the gold-standard of belongness, but, alas, this was not the case for most Tigrayans under the reign of Menelik and Haile Selassie. The child Mohammad has two strikes against him; he was a Tigrayan and a Muslim to boot.

Mohammed was born in an era where Christianity was an integral part of an Amhara and Tigrayan ethnonationalism. With the rise of the triad anointed kinds–Tedros, Yohannes and Menelik–the institutionalized exclusion of Muslims became the norm in the so-called Christian Island of Abyssinia. The Church was seen as the only unifying and mobilizing force that would bring the society that was divided and fragmented under the Era of Princes: Zemene Mesafnt. The Anointed Kings ushered in an era of intense intolerance, where Muslims in the Christian center were their primary victims. Mohammed’s ancestors were forced to adopt Christian names, to at least conform outwardly, and spare their lives. Some were forced to flee into Eritrea, Sudan and Somalia.

When religion becomes the basis of law, nothing good comes out of it. Anything that justifies exclusion is evil. The bane of harmonious existence and mutual respect is intolerance and the denial of differences. The unity-in-diversity should not be a gimmick slogan but a way of life. There is a strong temptation in both Eritrea and Ethiopia for Muslims to mirror the ugly legacy of religious ethnonationalism. It is wrong, short-sighted and has to be resisted. There is a better alternative where all communities of faith can live together and thrive. It is called secularism, but it has to come as a result of negotiation and not confrontation. Those pseudo intellectuals who have tried incessantly to portray secularism as a dirty word should be ashamed of themselves, and frankly, we have let them blabber for far too long. It has to stop.

One can’t deny that the heavy-handed and top-down approach of the communist regime of Mengistu Hailemariam has done more for the betterment of Muslims in Ethiopia, but any kind of imposition does not root out evil from peoples’ hearts and minds. More needs to be done and it starts by developing a curriculum that reflects history from all perspectives.

Mohammed’s book doesn’t suffer from the usual moralistic hyperbole and historical myopia associated with zealots who want to change the world; it is simply the story of an innocent child who went through the most egregious experience where his Christian teacher in Gonder would not even extend him the most basic human courtesy of calling him by his name. Mohammed happens to be the most popular name in the world, and perhaps, the one that invokes the most pride among the 1.8 billion Muslims. Alamin was also the nickname of the prophet given to him by the Meccans before he became prophet because he had a reputation for trustworthiness.

When Teberih and Nurhussien named their child Mohammed Alamin, one could only imagine their pride and love of their faith and their prophet. When little Mohammed memorized the Quran, he became a big hit within the Muslim community of Adwa and it earned him some much-needed bakshish. This was no small feat for a child who didn’t even understand Arabic.

To the man of the cross of Gonder, Mohammed was simply, “Ante ‘Slam.” Mohammed is not bitter. In fact, the love he displays towards his Christian Ethiopians and Ethiopia is beyond belief. The best men at his wedding were Christians and so were most the people who made his success possible, but there was something terribly wrong to be an Ethiopian Muslim in Ethiopia. During the two Eids, when Haile Selassie extended his holiday greetings to the Muslim community, the Muslims go through the most painful and demeaning experience because it was in those times that they became acutely aware that they are not regarded by their Christian counterparts as co-owners of their own country. The king would refer to them as “Muslim residents of Ethiopia.” What a disgrace?

During his sojourn in Algeria, my friend Suleiman A. Hussien was once asked by an Ethiopian fellow, “Why aren’t you proud of being Ethiopian?” Suleiman retorted, “Be glad I’m not Ethiopian. If I were, I would be the least proud. Nothing would infuriate me more than to be regarded as a resident Muslim in my own country.” No wonder the overwhelming majority of Eritrean Muslims were against union with Ethiopia.

The problem in Eritrea, the so-called Abbyssinian periphery, is not as bad as the Christian center in Ethiopia, but the degree of badness should not be used as an excuse. An Eritrean Muslim friend of mine, Derie Mohammed Debas, the son of martyred EPLF father and sibling to a martyred EPLF brother and an EPLF Tegadalit, who made it alive and now works for the Eritrean government, had to delay his urgent travel to Europe because no one at the Immigration Office could read his Muslim marriage certificate, Aqeda, written in Arabic. There were five windows open and most of them were not busy. They told him nonchalantly to return with a notarized Tigrinya translation. I was not sure if I were appalled by their stupidity or callousness, but it showed me that we have a systemic exclusion in Eritrea.

If we are to root out the systemic exclusion against Muslims in Eritrea, we first need to let the bells of freedom ring in our hearts. What happens to the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” If you’re an Eritrean and were not perturbed by the data of civil servants and the military leadership that Ahmed Raji presented to us, then, our problem is much deeper and much more concerning.

Just imagine a Tigrayan Muslim of Axum, who is not allowed to build a mosque in his native town. I completely understand the importance of Axum for all Tewahdos, and I am one and proud to boot, but the preservation of our Tewahdo heritage should not come at the expense of Muslims’ rights. Our humanity should be much more important than any faith we follow; afterall, the essence of all faiths is the ennoblement of our humanity.

The Tigrayans could follow the Vatican model and give the Archbishop of Axum (Nubura ed) his own sovereign quarter, but making the entire city inhospitable to mosques is simply wrong and it contravenes the Christian precept of loving thy neighbor.

Being aware of prejudice and systemic exclusion does not make one a bigot. It is the first step to taking actions that can help in eradicating injustices. We need to be on the side of those who speak against injustices. One thing that life has taught me is that those who risk their life in speaking against wrongs are hardly wrong, and imperfect as I am, if I have to err, I would rather err on their side.

The world can be a terrible place; it often makes us feel lost, but it can also be an amazing place where the once lost could now be found. I don’t have to agree with Islam to defend Muslims, all I need to do is speak against injustice. Let’s not let silence kill us. Our initiation into humanity starts with a cry, that is when the battle lines are drawn against our mortal enemy, silence. When we finally lose the battle against silence, we die. From the cradle to the grave, let’s speak up and pump up the volume.

Tolerance and mutual respect is the only way a harmonious existence is possible in a pluralistic society like Eritrea and Ethiopia. Any religion that serves as an integral part of ethnonationalism or a basis of a national law would be a recipe for disaster and we need to speak up against it wherever we are. And it is for this reason that the right to freedom of expression is a fundamental human right. Expression, verbal or written, is the best way we express our humanity. I want to speak up against past and present injustices in whatever religion and ideology they are justified; it is the only way I should live and the only way I want to live.

In reading Made In Ethiopia, the personal history of Ethiopia will be unfolded through the prism of a Muslim Ethiopian. It is about time we listen to all the voices that make us who were. When we silence others, we are silencing a part of us. Personal stories of the likes of Mohammed Alamin Nurhussien open our eyes and help us imagine ourselves in the shoes of others. It makes us better citizens and even more better people. Both Christianity and Islam teach us of the importance of compassion but what is compassion if it is not preceded by empathy. Stories help us to empathize and Made in Ethiopia is full of it.

______________

A copy of Mohammed A. Nurhussien’s book can be purchased directly from the publisher RSP or Amazon. Please click on the links: Red Sea Press, Amazon

Semere Tesfamicael Habtemariam is the author of Reflections on the History of the Tewahdo Orthodox Church History of Tewahdo Church and Hearts Like Birds Hearts like Birds. He can be reached at his email: weriz@yahoo.com

Awate Forum