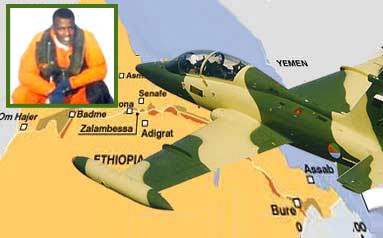

Dejen Ande Hishel: The Prison Breaker

On February 27, 2014, Dejen Ande Hishel, 38, an Eritrean fighter-jet (Mig-29) pilot and trainer, escaped from a maximum-security Eritrean prison in Asmara, where he had been held in captivity without charges, a verdict, or a day in court, for fifteen years. While his whereabouts have not been disclosed, it is safe to say that he is no longer in Eritrea: Assenna.com, a London-based independent Eritrean website which broke the story, also conducted a series of phone interviews with him where he narrated his biography, the circumstances that led to his arrest, his detention, and his escape.

The interview, which is in Tigrinya, is available on youtube in a series of videos (Part 1 through Part 6 one-hour interviews*, which were conducted in May 2014.) Dejen is remarkably articulate and a gifted narrator: his story is so rich and so full of detail and philosophical musings, it would be impossible for anyone who attempts to translate it into any language to do any justice to it, and we will not attempt it. Instead, what we will provide is a summary to help those who don’t understand the Tigrinya language get some idea as to why Dejen’s interview with assenna has been such a sensation with Eritreans: why it has at once depressed Eritreans—for the great injustice done to innocent Eritreans by the outlaw regime in Eritrea—and, at the same time, inspired them that the Eritrean spirit is not broken, that 15 years after imprisonment people like Dejen still exist: unbroken, defiant, bold and blessed with clarity of thought and action.

Below is a summary of the interview. We have added some notes in brackets to assist English readers who may not be familiar with Eritrean history, as well as some footnotes to provide additional information about the prisoners mentioned in Dejen’s narration.

Assenna.com – Dejen Ande Hishel Interview Summary

Early Childhood:

Dejen Ande Hishel’s family is from Elabered, Eritrea. [Elabered is on the road between Asmara and Keren. In the 1940s-1960s, Elabered was famous for its orange groves, tomato gardens, and dairy farms which were established by Italian entrepreneur De Nadai. In the 1970s, Elabered was the sight of many battles for Eritrean liberation. One of the toughest was when the EPLF and ELF were forced to withdraw from territories they had liberated just a two years earlier: in November 1978.] The young Dejen, then 2-3 years old, was evacuated, along with his entire family to Keren, where his mother worked in a hospital that treated wounded combatants and,eventually, to Sahel.

“Dejen” which means fort or garrison in Tigrinya, was a nickname given to him by his mother’s friends when he was just a baby.

His earliest memories were of Ethiopian fighter planes pursuing and bombing the retreating Eritrean combatants and civilians, who were journeying to EPLF’s base at Nakfa in Sahel province (northern tip of Eritrea.) His earliest memories include hiding in caves and emerging covered in dust when the bombing subdued, and witnessing the death and carnage of the bombings.

By 1978, his entire family—his father, his mother, his three siblings—were all enlisted in the EPLF. As a child, he was enrolled in the “Revolutionary School”, [a school run by the EPLF for orphans and children of combatants] and was literally raised by the revolution. [Thus, in 1991, when Eritrea became independent, he was about 16 years old.]

Eritrea-Ethiopia Border War (1998-2000)

[Several years before the war, the Eritrean government had decided to establish an Eritrean Air Force. Dejen was one of a few who was chosen to enlist in its academy. When the war broke out, both governments were in a mad rush to strengthen their air forces; and Dejen was trained by Russians how to fly Mig-29. The Ethiopian Air Force flew Su-27s during the war.]

Dejen describes the Russian training that he and his colleagues received as inadequate and says that he was shocked when he was given a certificate from the Russians that not only was he qualified to be a pilot but a trainer pilot. He protested his premature graduation but to no avail. He concluded that the Russians were more interested in meeting the goals of the higher-ups (graduating students quickly) than meeting the goals of the trainees.

Dejen says that the Eritrean pilots, particularly him, who was certified as a trainer, were lacking confidence in their abilities, as they had not been taught the fundamentals, nor had they logged sufficient flight hours.

In the Badme Front War [February-March 1999], he and his childhood friend Yonas Misghinna, were sent on missions. The two improvised that the best way for them to learn what they hadn’t been taught by the Russians was to copy the more able Ethiopian Air Force pilots. At the same time, they considered their job defensive: to harass the Ethiopian Air Force pilots and making it harder for them to conduct their bombing sorties.

Dejen explains the three-steps of conventional warfare: first the fighter-jets are sent to conduct bombing; this is followed by artillery shelling, which is then followed by infantry fighting.

In one of his missions, Yonas Misghinna (Dejen’s childhood friend) is downed in the Badme area. Dejen is sad and angry and filled with a sense of wanting to avenge his death. Dejen explains that standard protocol when a plane is downed is to conduct an assessment to avoid a similar mistake and, in the meantime, one must, at the very least, avoid making a pattern of the circumstances that led to the downing: altitude, place, etc. Yet, notwithstanding this protocol, the Eritrean regime sent another Mig-29, this one captained by Samuel Girmay, to the same place where Yonas’s plane was downed. And it met the same fate: Samuel, too, was downed.

Subsequently, it was learned that the planes that the Russians sold Eritrea were not new but used and malfunctioning. The pilot eject button did not work; the parachutes did not open. And two young pilots were killed at the same place.

The Badme war was followed by the battle of Igri-Mekel [in the Tsorona front: one of the most intense 4-day battles of the Eritrea-Ethiopia border war: Eritrea claimed it killed 10,000 Ethiopians and Ethiopia claimed it killed 9,000 Eritreans.] At this battle, a decision was made that Dejen could not comprehend: he was told that the fighter jets are grounded and would not participate in the battle. To Dejen, this made no sense: the battle front was only 80-90 [corrected distance] kilometer distance from Eritrea’s Air Force base in Asmara, and the pilots could make relatively safe sorties and come back.

Dejen Is Arrested

While the battle was still raging, on March 23rd, 1999, Dejen, then 23, had completed his shift when he was approached by government officials who told him that there was a guest who wants to see him. Still wearing his flight suit, he was escorted to a car where he was accompanied by five individuals (including the driver.) At the time, he was thinking that he was going to be sent on a special mission.

He was taken to the 6th police station in Settanta-Otto neighborhood of Asmara, where he was put in a cell. An interrogator told him that he is to talk with him and only him but that this wouldn’t happen that night. The next day, Dejen, fully convinced that it is all a misunderstanding, packs his belongings and gets ready to be sent free.

That didn’t happen. The visits of the examiner become less frequent. The examiner examines nothing: he doesn’t ask him any questions, nor does he provide answers. Only requests that he [Dejen] be more patient.

Days become weeks, weeks become months, and months become years.

He is transferred to Carcielli, a maximum-security prison in the heart of Asmara. He is held in a cell [locally known as “cella.”] Prisoners are allowed to sit in the sun for only half-hour a day on a rotating basis: one week it is the morning sun, the next week it is the setting sun. This, he explains, is a huge improvement over his conditions in the 6th police station where he was taken outdoors only once every two months.

Prisoners are not allowed to talk to each other; nor are they allowed to have conversations with the guards. The only way they communicate is by writing graffiti on walls: often, the graffiti on walls are their arrest dates. They also communicated by whistling [although all these forms of communication are a simple “I am still here/I was here.”]

Dejen explained that sometimes, past midnight, past 1 or 2 am, piercing cries would penetrate the entire prison. He said that these cries are either due to a prisoner having a primal scream to relieve the pressure and frustration of being confined for reasons he or she doesn’t know. Or they are due to someone being interrogated and tortured.

Dejen explains that there was a tiny window in the prisoners’ toilet room that provided a view of the outside. The prisoners called it “wikileaks.”

Dejen narrates one incident that provided an opportunity for prisoners to meet one another: a drunk driver ran his vehicle into the walls of the compound. The prison wardens moved some of the prisoners from their cells. And it was there where he first met prisoners like Nesreddin AbulKherat1, [a Sudanese national] who was arrested in 1997 for allegedly trying to assassinate Isaias Afwerki. Dejen describes that he asked Nesreddin if he really [on orders of Sudan’s Omer Al Bashir] tried to assassinate Isaias Afwerki and says that Nesreddin replied, “look for yourself, the two are best friends now.’ He also said that in 2006 he stayed in cell 26 together with Teweldemedhin Tesfamariam, [a diplomat who was called for a meeting to Eritrea and arrested.]2.

Dejen was also able to confirm that General Bitweded Abraha3, Ermias “Papayo” Debessai4, Aster Yohannes5, Ali Alamin and Kiflom Gebremichael6 were held in the same prison. He also says that he has a more comprehensive list of prisoners and “we will disclose it in due time.”

Dejen says that he was made aware of Aster’s presence because he heard her screaming in the still of the night.

According to Dejen, if vehicles leave at night with prisoners and return only with their belongings, it is commonly understood that the prisoners had been killed. Thus, Dejen assumes, that Ali Alamin and Kiflom Gebremichael (two Eritreans who worked for the American embassy in Eritrea and were arrested in October 2000) were killed.

Dejen explains that it wasn’t until two years after his arrest that he was finally visited by his family. He emphasizes that his entire family [father, mother and siblings] had been enlisted in the EPLF and served the revolution. When they came to visit him, he was hoping for some answers: why he was arrested. Instead, he found out, that his family had no answers, only questions: they wanted to know why he was arrested.

Dejen’s Escape

Asked by the interviewer (Assenna’s Amanuel Iyasu) as to when he gave up on the government, he said it took him four years from his imprisonment. He said that the EPLF was his world: the revolution had raised him. It took him years to realize that by merely asking what his crime was, he was accusing the government of imprisoning innocent people and thus committing a crime and increasing his punishment. It took him years to realize it wasn’t the prisoners who had committed crimes, but it was the government which was committing a crime by detaining the innocent. Dejen explains that he had written thousands [too many to count] of letters addressed “To Whom It May Concern” describing his condition and demanding that he know of the charges against him and that he brought to a court of law. At some point, explains Dejen, he had asked who this “to whom it may concern” is and he had been told it was Isaias Afwerki. Asked if he had ever received any written response, Dejen explained that the only responses he received were oral and they were not answers but stalling by referring to the general condition of the country [the so-called no-peace no war situation.] Whenever he asked his interrogators what the charges against him were, he was told “what do you think they are?”

Four years after his imprisonment, he was convinced that he would never get justice, would never get released by the government. Six years before his escape is when he decided that if he was ever going to be free, it would have to be by escaping from prison.

He equated those who were incarcerating him with a stick: if somebody hits you with a stick, your argument is not with the stick but the person using it.

For years [for 6 years], Dejen explained, he plotted his escape. He had given himself some conditions: that his escape would not be dependent on anyone—he was going to plan and execute his escape on his own. That once he starts, he wouldn’t hesitate and never look back and would see it through.

He said that it took years for him to escape because the opportunities for escape were rare; that when the opportunities are presented, they get frustrated at the last minute, or there is a loss of nerve. He says that the biggest challenge that has to be overcome is a psychological one.

Dejen had noticed that one of the prison warden’s vehicles, the one that transported prisoners to hospitals, which was parked in the compound, always had mechanical problems. Because of that, the prison guards would sometimes leave the engine running since, if they turn it off, it presented problems for them in restarting it.

The opportunity he wanted was: this vehicle, with engine running, but unaccompanied by other vehicles. Most of the missed opportunities were because there were always 3 other vehicles and a motorcycle. Another missed opportunity was that, from his prison cell, he couldn’t tell whether the engine was running or not because, when there were power blackouts in Asmara, the guards brought generators, which drowned out the sound of the engine.

Then Dejen found another clue. When the engine was on, the vehicles’ side-view mirror would vibrate and, from a specific location, (the window in the toilet which they called “wikileaks”) the side-view mirror would vibrate the reflections of the sun. This, then, was his clue that the engine was on and the vehicle was running idle.

On the day of his escape, on February 27, 2014, which happens to be the anniversary of the death of his best friend pilot Yonas Misghinna, the conditions were optimal: the vehicle was not accompanied by other vehicles in the compound, and the engine was on. He walked to the vehicle and got in. His first challenge was that the vehicle was not facing the gate but the prison cells. Still, he drove it around towards the gate. The compound has multiple gates but they were open. The guards were playing cards and were not attentive. Dejen explains that this is because the oppressor is never as attentive as the oppressed. He had made a decision that he would crash through the final gate knowing that, if it is a strong gate, the vehicle would smash against it and stop. But he broke through the gate which was not strong.

The police officers gave chase, on foot: none were on vehicles.

Here, his escape vehicle stalls; he attributes this to his forgetting how to drive a car [in Eritrea almost all cars are manual shifts.]

He re-starts it and drives making left turns and right turns. I feel free, explains Dejen. Ahead of him, pedestrians motion to him to stop because the police pursuing him were instructing him to stop. But he doesn’t. The police do not shoot because he was in a crowded street. A policeman reaches out to him and grabs him by the hand, but Dejen breaks free.

He drives north, towards Akhria neighborhood. At some point, he reaches a dead-end, abandons the vehicle and walks on foot. Walking, he tries to determine if he stands out among the crowd and based on the double-takes people were making, he determines that he is.

Turning right, going over a fence where people dump their trash, he heads north. He comes across a huge ravine—a steep slope down, and a mountain ahead. He turns his clothes inside out, and he walks and rolls-down the hill. Unable to reach a foot hold, suspended, he fears for his life, that this is how he is going to die: birds fly, startled, he lets go of his grip, and lands on a foothold, relieved that he is still alive.

Interviewer [Amanuel]: Earlier in the interview, you had said, “The dead don’t fear death.” What happened now….

Dejen [laughing]: Well now I am “kem sebey” [an ordinary person]…

Crawling, walking, rolling down, Dejen makes it down to the bottom of the hill. Only to be confronted by howling monkeys. Dejen explains that he is anxious now, thinking, I got past [human] police only to be discovered by howling monkeys. Nonetheless, he goes past them and makes his escape….

[*The part of how he crosses the Eritrean border is not yet explained.]

Footnotes

Correction: We made transcribing error on the distance, it is not 25-30 kilometers but 80-90.

1. On May 25, 1997, Eri-TV broadcast the “confessions” of Nusreddin and how he was sent by Sudanese intelligence to assassinate Isaias Afwerki. The video of the two-part interview can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Q34iicHlPY

2. Teweldemedhin Tesfamariam was the deputy chief of mission in the Eritrean Embassy in Nairobi. He has been in jail since April 2003.

http://web.archive.org/web/20030502000807/http://www.awate.com/artman/publish/article_1295.shtml

3. Bitweded Abraha is one of Eritrea’s most remarkable men. Arrested in October 1991 for speaking out against the Meles-Isaias cozy relationship in regards to Asab, he broke out of jail in 1995 and forced the Eritrean government to admit that it had no case against him, went back to prison, got released in 1997, went back in 1998: all because he dared to warn Eritreans of the looming dictatorship. His story can be found here: http://admasna.blogspot.com/2005/12/bitweded-abraha-13-years-solitary.html

4. Ermias Papayo Debessai is a member of the PFDJ’s Central Committee. He has been in prison since 2003, when he was arrested with his sister Senait Debessai. It was his second arrest. http://www.ehrea.org/dear.php

5. Aster Yohannes is a veteran EPLF combatant who also happens to be the wife of Petros Solomon (a member of the G-15 who has been detained since 2001.) Aster Yohannes, who was studying in the US when her husband was arrested, returned to Eritrea on December 11, 2003 after she was given personal assurances by then ambassador Girma Asmerom and Isaias Afwerki that no harm would come to her if she returned to Eritrea to be re-united with her children. She was arrested at Asmara Airport and her family, there to welcome her home, returned without seeing her. Her story is found here: http://www.friendsofaster.org/

6. Ali Alamin and Kiflom Gebremichael worked for the US embassy in Eritrea in 2000. At the time, there was a fledgling private press in Eritrea and part of their job was to translate the news/opinion written in Tigrinya into English. They were arrested on October 11, 2001. http://iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/texttrans/2002/10/20021017201028corey@pd.state.gov0.9141504.html#axzz33PzeY2VL

The United States has made information on the whereabouts of these Eritrean nationals one of the conditions for normalizing relationship with the Eritrean regime. But since then, the Eritrean regime arrested two more embassy employees in 2005, and two more in 2009 and accused them of “human trafficking.”

Awate Forum