ERITREA: WHAT IN A NAME

A self-contemplation that was circulating for some-time in my head was brought to surface when the curious touche-à-tout Saleh Gadi Johar humorously discussed the origin of the name Eritrea in his Negarit No 123 entitled “Eritrea and Eretria”.1

Where did the name come from? And who coined it?

Johar did his own research. He was not satisfied by the Latin origin of Mare Erythraeum, too convenient and too straightforward to make it mythic. He didn’t want to settle as he did for his favorite natal city, Keren came from Keren. Period! For our beloved Eritrea, he needed something more crunchy and more legendary. Johar surfed from Indian ocean to Greece and fell upon an ancient Greek city, Eretria. A city, giant despite its size, envied by everybody. Civilizations fought to subdue it, including the Persians (the USA of that time), a mirror image of Eritrea today. See Negarit-123 for more.1

Following Johar’s footsteps along with some serious search in the same European vicinity there appears to be another plausible explanation from no other place than the former colonizing country, Italy. Interestingly the name Erythraen is smack in the middle of the most religious places on earth, the Vatican City, right in the Sistine chapel, painted by the master of masters Michael Angelo who labelled it ERITRAEA underneath the sybillic painting. For a legend, it doesn’t get better than this. Artistic, Mythic and Mystic, all in one. Michael Angelo represented the Erythraen sybil on the ceiling of the great chapel. Sybil is prophecy, Erythrae an Ionian city now part of Turkey. In the city of Erythrae, in ancient Greece, there were several prophecies. The most notable Sybil and venerated by Christians was the one that drove Michael Angelo up to the ceiling to paint Eritraea along the creator and his creations. That sybil was the one that prophesied the coming of the redeemer (Jesus Christ). Hurrah! we outdid the Ethiopia Sybil “Ethiopia shall soon stretch forth her hands unto God (Psalm 68:31)”.

Well before confirming or rejecting this hypothesis, let’s go see what the Italians said.

In 1890, Fortune fell upon Francesco Crispi to be the Prime Minister of Italy to present to King Umberto I, the decree announcing the bringing together of Italian colonies acquired along the Red Sea in the preceding years. Here goes the decree of January 1: Regio decreto 1.1.1890, n. 6592, i possedimenti italiani nel Mar Rosso sono costituiti in una sola colonia col nome di Eritrea. Google translated into: The royal decree 1.1.1890, n. 6592 the Italians possessions in the Red Sea are constituted in a single colony with the name of Eritrea.2 Boom!!! The first day of the year 1890, the decree containing a new consolidated colony befell upon the Italian parliament. The members were previously accustomed to hearing ‘la nostra Massaua’, ‘la nostra Assab’ and ‘la nostra Saati’ eccetera. From that day on, they had to get used to the new denomination “la nostra Eritrea” and to finding the additional financial burden the new colony brought over the already overburdened Italian budget. I can visualize the deputies glancing right and left at each other looking for anyone to decipher the meaning of Eritrea and on where the money for it is going to be taxed from.

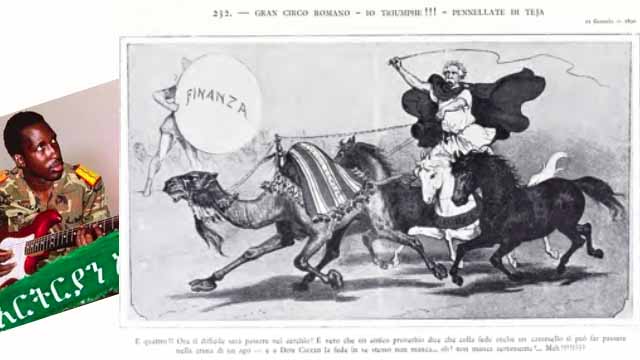

Also of significant note was Crispi’s monopoly of power, adding another responsibility to his premiership, minister of interior and acting minister of foreign affairs. This was hilariously captured by the caricaturist of the time Casimiro Teja by representing Crispi’s riding a 3-horse and 1-camel ridden circus chariot, the 3 horses for his existing responsibilities, the camel for his new colonial responsibility, and a finanza (finance!) screaming at the arrival panel.3* “Crispi” gave the name Eritrea to Eritrea. Would it be too caricatural to say Casimiro Teja gave Eritrea its national Emblem? Teja’s imagination was premonitory to the essential role played by the Camel in serving as a train transporting goods, arms and the wounded in the fight for independence of Eritrea.

Italian authors attribute the coining of Eritrea to Crispi’s personal secretary of the time and the already well-known man of litrature Carlo Dossi.4 It should also be mentioned that an Eritrean author in French, Nafi Kurdi, had captured this information in his book written following Eritrea’s independence.5 Italy’s visionary son, Carlo Dossi in the 1870s had authored a book entitled “la Colonia Felice (the happy colony)”. Writing on Dossi, Francesco Lioce (2014) makes a link between the fiction Dossi wrote a decade previously and his interest in the colony and in naming it in 1890.4 It appears that the credit of naming was not duly attributed to Dossi at the time. Skimming through the political discourse given by Crispi in his parliament, it is interesting to note Crispi’s hesitation to talk clearly about the name ‘Eritrea’. He also stayed vague by not answering directly to interrogations from his colleague deputies on this new colony.2 Reverting to the possible Sybillic linkage, it is not farfetched to imagine Crispi with his bag holding secretary (Dossi) going to Pope Leone XIII to discuss European affairs and possibility of reconciliation with France, and on the way passed through the Sistine chapel. There, hanging their neck on Michael Angelo’s Eritraea Sybil the inspirational name for their colony fell upon them. If only things were so simple and locking together! Unfortunately, the more I push this mythic possibility the more I am dragged back by reality. It would be far-fetched to expect mysticism from a Jacobin Crispi6 and an atheist Dossi (it.wikipedia).

If we the inhabitants of Terra di Mare were consulted, we would have suggested ምድሪ ባሕሪ and stayed away from the difficulty in pronouncing our baptismal name ኤለትራ, ኤለትሪያ, ኤሪትራ ecctera. Nevertheless, we love the name that was thrown at us. We adopted it readily and placed it in our heart. We love Eritrea ኤርትራ to the point that we don’t even question where it came from. By reading the usual history books, one gets the usual short sentence saying the name was derived from Mare Erythraeum. It was the case when I turned the pages of ኢጣልያዊ መግዛእቲ ኣብ ኤርትራ (Italian colonization in Eritrea) by the Zemhret Yohannes (central committee member of PFDJ).7 I could have stayed Zen like Zemhret’s and other’s books on the subject, but Johar’s inquisitiveness and a knock on mine pushed me to trample the historian’s domain of looking around.

It is now well established that the writer, diplomat and politician Carlo Dossi is the baptismal Godfather of Eritrea. Where did he get the idea from then? Dossi is an accomplished linguist in addition to his aforementioned qualities, able to interpret the history and geography of the region and name Eritrea most likely from the sea of Eritrea. Moreover, the presence of his Italian naturalist and missionary voyagers discovering habitats, acquiring land and documenting everything they observe could have given enough material for Dossi to depend on. Indeed Giuseppe Sapeto, the missionary who acquired the first implantation for Italy and Arturo Issel a renowned malacologist, in the books they published, the former on Assab and the later on molluscs profusely use the adjective Eritreo (Eritrean) to describe a fauna, a shore, a marina, a bay or the volcanic land or shell that anyone who is reading their books would be struck by.8,9,10 Others before them have used the latin term Erythraean from Mare Erythraeum to describe the fauna and flora. Therefore, it is conceivable that Carlo Dossi was inspired reading his compatriots books.

The question on why the Mare Erythraeum was called Erythraeum is a long story that Saleh Gadi Johar had touched upon.1 There are several possibilities. From the flora or fauna of the red sea or from Erythras king of Persia administering the area. Here is an old but very useful reference for these and other possibilities.11 Let us also not forget Erythras the son of Poseidon the God of the sea (Wikipedia), another mythic possibility from Greek mythology!

References

1 – Saleh “Gadi” Johar, March 2021, https://awate.com/eritrea-and-eretria/

2 – Discorsi di politica estera pronciati di Francesco Crispi, Presidente de consiglio, Ministro del interno, e Ministro ad interim degli affair esteri. Aprile 1887 – gennaio 1891. Roma, tipografia delle mantellate 1892.

3 – Caricature di Teja 1856-1897, annotate da Augusto Ferrerò. Pasquino. Torino. Viarengo-RE Editore, 1900. *To view the cartoon, type Casimiro Teja in google books. Then either search page 299 in the preview search or download the book and go to page 299 or cartoon No 232.

4 – Francesco Lioce, Dalla colonia facile alla colonia Eritrea. Cultura e ideologia in Carlo Dossi, Loffredo, Napoli, 2014. From a review by Fabrizio Miliucci, Università degli Studi Roma Tre.

5 – L’Érythrée, une identité retrouvée. Nafi Hassan Kurdi · Karthala, Paris 1994

6 – Jemolo A.C. Crispi, Uomini e idee. Vallecchi Editore Firenze, 1922

7 – ኢጣልያዊ መግዛእቲ ኣብ ኤርትራ 1882 – 1941. ዘምህረት ዮውሃንስ. ሕድሪ፡ ኣስመራ፡ 2010

8 – I Suoi Critici Del Professore Giuseppe Sapeto Assab. Stabilimento Pietro Pellas Genova, 1879.

9 – Malancologia del Mar Rosso, Riceche Zoologiche e Paleontologiche. Arturo Issel. Editore dell Biblioteca Malacologica. Pisa, 1869

10 – Viaggio e missione cattolica fra i Mensâ, i Bogos e gli Habab con un cenno geografico e storico dell’ Abissinia. Giuseppe Sapeto. Roma, 1857

11 – The Name of the Erythraean Sea. Wilfred H. Schoff. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 1913, Vol. 33 (1913), pp. 349-362 Published by: American Oriental Society. Available at Jstor.

Awate Forum