Azien Yasin, the Famous Freedom Fighter I never knew

Azien Yasin was a brilliant freedom fighter who had great influence on the Eritrean Liberation Front. He was present on the battlefields of Eritrea when the armed struggle called for incredible feats of bravery. He was there among the distinguished fighters who went above and beyond the call of duty during that intense period of relentless attacks by the Ethiopian forces. Certainly, he played an important role in keeping the struggle going by leading from the front, particularly at the intellectual level.

I can also say he was there when I was a wanderer and had scanty knowledge on what was going on in Eritrea. Yes, I was oblivious to who was paying the heaviest of prices in the earlier battles that pitted the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), our freedom fighters, and the Ethiopian forces during the deadly battles that were responsible for the deaths of thousands of lowlanders.

Now, rather contemplatively, I look back to interrogate my conscience, naiveté and rashness and ask myself how on earth did I not know of this exceptional man for all those years. I can say I suffered from a bias-blind spot, a prevalent condition among many Eritreans, that made me overlook important historical facts and twisted my objective interpretation of our reality.

It is true that not all freedom fighters that showed unflinching courage and determination in withstanding the threat to Eritrea were recognised with gallantry awards before and after independence. If I say that the likes of Azien Yasin were systematically erased from the public psyche in order to make more room for the EPLF combatants, the victorious army, is not an exaggeration but a statement of fact. For our readers’ information, we are all witnesses to the kind of ‘victory’ the victorious brought to Eritrea; not liberty but utter misery.

What worries me the most is the fact that many of us are still content to live in blissful ignorance of our true heritage. During the armed struggle we were conditioned by the ‘Jebha Haradit’ (ELF combatants are killers) dogma that emanated from EPLF’s propaganda networks, a misinformation campaign that ushered in a convenient argument for our folly. And now, rather sadly, we still live on the periphery of our jaded reality.

Allow me to dwell on the subject matter a little longer. I acknowledge that I remember hearing Azien Yasin’s name being mentioned casually in my circles. Yes, I heard bits and pieces of his story as if he were an ordinary fighter. I confess dismissing him was easier than fostering the true nature of his progressive persona and the ELF fighters whom he represented; here I am referring to the patriotism, heroism and daring incursions the ELF conducted in urban areas during the armed struggle. Suitably, and rather irrationally, I chose to dismiss that part of our history on the double.

The fact is when we were young, we were not only zealous but also gullible; and we tended to be misguided easily. In fact, we were so carried away by the freedom frenzy of the time we couldn’t tell what was real, and what was made up. For others life felt like a toss-up whether they, the restless youth, would end up sympathising with the EPLF or ELF fighters. Somehow, I and many of my type ended up supporting the EPLF.

Later in my adult life I had inkling of how the EPLF continuously blamed the ELF in order to aggrandize itself (by mercilessly belittling it). Its eminence was based on successfully inventing an enemy figure to whom we assigned our fears and suspicions. I remember the time we referred to the ELF in negative and pejorative terms. Knowing full well of the tactics used by the EPLF against the ELF, I still chose to look the other way instead of clearing my conscience for my biased views.

Did my Christian upbringing and highland heritage play any role in the lopsided opinions I developed concerning the armed struggle? Of course, they did. I, including many others like me, automatically assumed that the ELF was a Muslim faction. Unfortunately, through the tinted prism of the time, I could barely make out ELF fighters as true patriots.

The fact of the matter is, the armed struggle for independence was started by Eritrean lowlanders (Muslims) because they were the ones who were most affected by unfair practices of the time.

I still remember when buses were being raided, trains were being derailed, students were rioting, and a few years later, aeroplanes were being hijacked by the so called ‘shifta’ (bandits, not freedom fighters).

When times were changing from the ‘Shigey Habuni’ era to ‘Webebat Adey’, more and more young urban dwellers began to flock to the wilderness to join the ELF. That era coincided with the publication of EPLF’s NeHnan Elamanan (‘Who we are and our Goals’) which is still considered a controversial document by many.

The document was not only published to highlight the identity of a ‘superior’ (the Ala group – Isaias’ faction) but also to implicitly sow seeds of discord among the fighters and hoodwink the public along religious divide, and cast suspicion on the ELF as a ghastly faction. In other words, NeHnan Elamanan managed to exploit, rather cunningly, the friction among the two factions by widening the gap between the Muslim / Christian social divide. In other words, its aim was to turn would be Christian recruits away from joining the ELF, and to marshal them towards EPLF’s trenches and garrisons.

In retrospect, I can say that the ‘manifesto’, instead of informing the unsuspecting public of the holistic setbacks of the time as it should be, it successfully reduced our ability to think both critically or independently by instilling adverse thoughts and ideas into our minds.

For example, it contained many gaudy and loaded claims such as this – ‘how should one opt to face butchery in the hands of ‘Jebha’ simply because one was born Christian?’ Good grief!

To the discerning reader, Isaias delivered a twisted manifesto that mirrored his twisted nature, which gradually poisoned the Eritrean political landscape forever.

Personally, it urged me to harbour negative attitudes, values, and beliefs towards the ELF. I premise my argument on this inference – the EPLF won the propaganda war and systematically persuaded many Christian recruits to accept a certain allegiance, command, or doctrine of the time (the NeHnan Elamanan doctrine which was based on bedevilling the ELF as if Isaias’ faction played no part in the discord that surfaced between the combatants).

In a few words, Isaias and his manifesto exploited our low propensity to change the face of Eritrean armed struggle whose rancour is still felt in our communities. It would not be an exaggeration to state it was designed to get readers riled up and angry. It was a wedge issue. It stoked fear or resentment among many non-discerning readers like me at the time. I can say it was some red meat for the susceptible highlanders!

Let’s leave the old discord between the factions and Isaias’ evocative manifesto played out against the backdrop of war of attrition aside and flesh out the facts surrounding the story of Azien Yasin.

To present the story of Azien Yasin it is probably better to start from Aligidir, his hometown.

A Short Story of Aligidir and its Provident Son

Aligidir, before it lost its lustre, was a fertile area near Teseney which was cultivated by the Italians. In the 1920s it was also the administrative and residential centre of the irrigated plantations developed by the Italians.

The Italians supplied the irrigation from the Gash River and made Aligidir their agricultural management centre. By 1913, they were all set to build dams and canals. However, since World War I was just around the corner, the work was delayed until the mid-twenties (1924-26).

But soon after, in 1928, when the dam was completed, 15,000 hectares (about 12 * 12 sq. km) of land was cleared. The area had a favourable climate and soil conditions for cotton cultivation and grain plantation.

The project was carried out under the auspices of an Italian parastatal agency (Societa Imprese Africane). The agency coordinated operations, hired a number of local people, lent money to farmers, distributed seeds and seedlings, imported farm equipment, and provided water, and the agency agreed to share the surplus and put the produce for retailing.

However, as Aligidir was turned into a ‘company village’, accommodations were built for the administrators and skilled workers in the camps. And agricultural labourers were recruited from surrounding rural areas. With this ingenuity they expanded Aligidir’s agricultural operations.

When the company built a school and clinic in Aligidir and started providing crucial services to its employees, it attracted many people from various parts of Eritrea and even from Eastern Sudan. The work was well established.

In the mid-50s, the company had the equivalent of 2,000 Eritrean and 15 Italian employees, and housed 12,000 temporary workers and their families. One can say the community that settled in those farm camps made a lot of progress. One can also refer to the Sheikh Adin family that was well rooted in that community played a significant role in its existence.

The Sheikh Adin family was from the Biet-Juk community; and it had the privilege of producing a community here that was characterised by racial integration and excelled in education. In the future journey our struggle, it is from this educated community the leadership of the national revolution in the western lowlands managed to emerge.

The children of Sheikh Adin married people who worked in that agricultural agency. To name a few the father of Idris Osman Gelawdeos, Jabir Said, Omar Jabir married into the Sheikh Adin family. Yasin, the son of Sheikh Adin produced Azien Yasin.

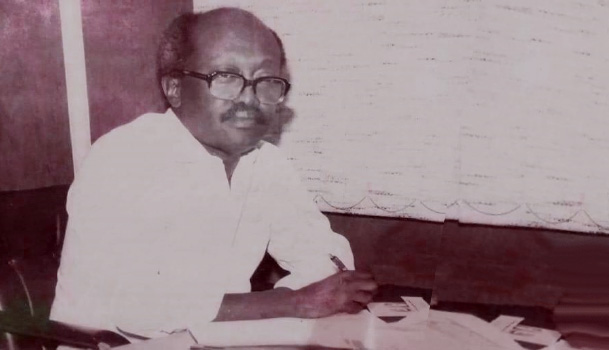

Since the narrative has linked Aligidir with Azien Yasin, let me provide a brief description to introduce him to our readers: Azien Yasin (1941–1996) is identified within the ELF as the one with the most progressive ideals and leader of the Labour Party.

After completing his secondary education in Sudan, Azien Yasin enrolled at Khartoum University in 1960s. There, through the student movement, he became acquainted with the Sudanese Socialist Party.

After graduating from university in 1965, Azien joined the ELF. He was then elected as the head of the Revolutionary Command’s information department in Kassala.

Predicaments in the ELF

During the time when internal crises within the ELF intensified, Azien was right there in quest of progressive remedies for those multiple movements that sprouted.

Azien Yasin (second from left), with Ali Ishaq, Ibrahim Totil and Hamid Mahmud

It would require an extensive and in-depth research to illuminate the movements of the 1960’s within the ELF. One can say the mid-sixties (especially 1967 to 1970) were a time of great upheaval and change for the ELF. In fact, it was a very challenging era. To name a few of the challenges, the establishment of the Fifth Division, the Islah movement, the Labour Party movement, the establishment of the Tripartite Unity, the Adobha Conference and so forth. It requires a longer commentary to examine all the events properly. For now, let’s concentrate on the events of the Islah movement and the emergence of the Labour Party.

The first decade of the revolutionary struggle went well. However, Jebha failed to take advantage of the gains to reinforce its inner mechanisms. Soon it was plagued by ethnic factionalism and internal rivalries which weakened the struggle precipitously.

As the problems intensified, they flared up, and those demanding change stepped forward. Thus, the Islah movement was sparked. Islah, I would say for the sake of harmony and unity, strongly opposed the wayward leadership which was guiding the struggle heedlessly. Many fighters mistakenly viewed Islah as a counter-revolutionary movement. Its leaders were Abdella Suleiman and Abdulkadir Romodan.

The second movement was introduced through the establishment of the Democratic Labour Party. The movement, by implementing leftist ideology, sought to introduce reforms. To this day, some veteran fighters say that it did succeed to a certain extent.

The movement was launched in 1968 under the influence of the Sudanese Socialist Party. It was formed as a secret party – like Haraka, the older movement of the late 50s and early 60s. Its leaders were Azien Yasin, Ibrahim Mohamed Ali, Saleh Ahmed Iyay, Ahmed Adem Omar, Mohamed Omar Yahya, and Mahmoud Mohamed Saleh,” says Woldeyesus Amar (in his book ‘Students in Struggle’). He then mentions that Hruy Tedla Byru joined them in 1970.

Nevertheless, it can be said that the Democratic-Labour-Party was a movement that emerged to rectify the mistakes within Jebha.

In 1971, Azien was appointed as a member of ELF’s Executive Committee. After his appointment, he headed the Information Department until 1975 and the Foreign Relations Office until 1976. ‘But he was prevented from reaching the highest leadership position by Abdella Idris,’ says Dan Connell, author of a comprehensive historical dictionary of Eritrea. The charge that Abdella Idris and his colleagues made against Azien was that he was ‘extreme leftist’.

Of course, Azien, according to Dan Connell, acted as the main convenor of the ELF in leading delegations to attend meetings with the EPLF (1977), East Germany (1978), and the Soviet Union (1980).

Historical documents show that Azien headed the secret party he and his colleagues founded until 1982, when it ceased to exist completely.

During those tense times, however, Azien remained in the mainstream of the ELF (Revolutionary Council), from the very beginning – when it was led by Ahmed Nasser until the time of unity endeavours (1984).

Azien Yasin suffered from bad health during his peak years. He suffered from diabetes. When his diabetes went out of control, he was transferred to Saudi Arabia for treatment and work from there as a journalist.

After independence, however, he returned to Eritrea. He was a member of the Constitutional Commission. He moved on to a new chapter in his life. As Dr Bereket Habteslassie (Chairman of the Constitutional Commission) led the commission, Azien Yasin was his deputy. However, his health did not improve; and he had to return to Saudi Arabia to undergo further assessment before he completed his constitutional work. Unfortunately, he died there in 1996 from a kidney failure.

Azien’s profile is basically as I have briefly described it above. To see the other side of Azien, his character, let’s move on to excerpts of my conversation with Tesfay Woldemikael (Degiga).

Azien According to Tesfay ‘Degiga’ Woldemikael

Tesfay is a veteran former ELF freedom fighter. He committed his life to the cause ever since his student days at Santa-Familia (Asmara University) to the present.

“I came to know Azien Yasin back in 1973 – that is after my field training” Tesfay said. “FYI, I believe that there are other comrades who knew him better than me” he added. Tesfay remembered Azien as the first veteran who taught him the ins and outs, and the political aspect of the Eritrean struggle. Years later, they were on the ELF’s executive committee together.

“Azien was one of ELF’s political ideologues. And to me, as I’ve already mentioned, he was my mentor. It was based on the imprints that he left on me that I set myself up for our struggle. In other words, what turned my nationalist feelings into practical campaigns were Azien’s briefs,” Tesfay recalled.

“I particularly remember him well for his vast knowledge. His ability to analyse political developments in our region was uniquely captivating. And his mastery of the English and Arabic languages was riveting” he added. Tesfay mentioned that Azien was the head of the Arabic news department at the time. He also added that Azien was very mature in his outlook and knowledge on Marxist-Leninist philosophy was awe-inspiring.

Tesfay went on to recollect that Azien was the kind who loved to dwell on research, and basically, he was someone his students would quote frequently – ‘Azien said this, and Azien said that’ amongst themselves.

“I remember Azien being approached by foreigners who came to observe the development in the battlefields.

“Additionally,” stated Degiga, “I see Azien as a bridge; by that I mean he served as a communication bridge between veteran and new recruits as the demographic and social direction of the struggle was changing at that time.

“Most of the veteran fighters were from lowlands of Eritrea, predominantly of Muslim faith. The new recruits were from the Christian side of the highlands. Azien worked to promote understanding between the two groups,” Degiga described Azien’s role.

“After training, when we went to our assigned places, every time we heard Azien was in our neighbourhood, we would follow him in groups. There was always something new to learn from him” said Tesfay. Tesfai also remembered some members of the group that travelled with Azien; namely, Mohamednur Ahmed, Ibrahim Gedem, Ibrahim Totil and Khalifa Osman.

To conclude Azien Yasin’s story, Tesfay Degiga said, “when Azien died, the Revolutionary-Council wrote a column in his honour, which underscored the fact that Eritrea had lost a great fighter”.

In short, the above passages describe the role of Azien Yasin during the Eritrean armed struggle for independence. His colleagues testify that he was kind, wise, skilled, firm in his principles and broad-minded. Recalling his time on the Constitutional Commission, Dr. Bereket Habteslassie, the chair of the commission, remembers Azien Yasin’s contributions with much admiration and a whiff of nostalgia.

Therefore, the story of Azien Yasin shows how big a role the ELF played in the battlefields of Eritrea, an aspect of our history which has received inadequate attention. Testimonies of veteran ELF fighters should help here in highlighting those incredible feats of bravery before it is too late. The surviving ex-ELF fighters have the duty to document their stories and that of their fallen comrades in order to keep their memories alive.

Personally, I would like to post-humously thank and honour Azien Yasin for his kindness and intellectual prowess, qualities we evidently miss in the current administration.

Awate Forum