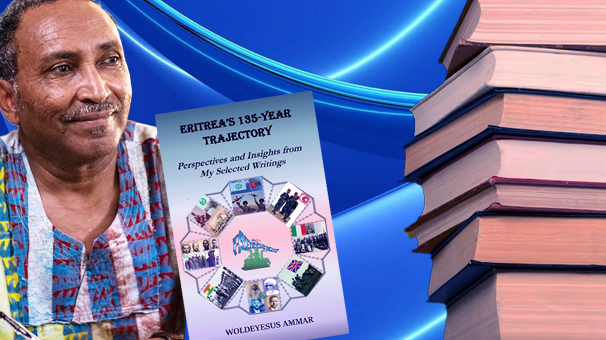

A Monumental Account of Eritrea’s Torment and Struggle

Eritrea’s 135-Year Journey: Perspectives and Insights from My Selected Articles by Woldeyesus Ammar is an unparalleled historical/political collection about the winding journey of Eritrea, spanning more than a century of historic odyssey—from Italian colonisation in 1890 to today under domestic authoritarian rule. In a carefully chosen collection of writings spanning over five decades, Ammar presents readers with more than an eye-opening historical lesson – Ammar possesses perhaps the ultimate “lived” testimony to Eritrea’s identity politics, its liberation war sufferings and triumphs, its heartbreaks and lost opportunities.

This book is both of scholarly value and reads like a memoir. Ammar writes not as a detached historian or observer from outside Eritrea, but rather as someone who lived almost two-thirds of its modern history, through the colonial era, federalism, the armed struggle, and victory in 1991, to the political disenchantment that ensued. As he explains in the preface, this is a work “written bearing in mind memories of post-Italy-post-Britain Eritrea relatively fresh at the time of writing” but also with an eye to how historical records were lost, destroyed or simply unavailable to many Eritrean combatants and activists.

Structure and Scope

The book is divided into 20 “Readings,” each excerpting content from Ammar’s previous articles or interviews. These readings span key periods:

- Italian colonial rule (1890–1941)

- British administration (1941–1952)

- UN federated era (1952–1962)

- Peaceful resistance movements (1940s–1961)

- The armed struggle (1961–1991)

- Post-independence Eritrea (1991–today)

The Table of Contents alone testifies to the book’s ambitious sweep — detailing its analysis of major wars, student movements, political betrayals, liberation leaders, massacres, and the psychological legacies of militarism. It’s an archive of Eritrea’s suffering, resistance and paradoxes.

Ammar’s Historicism: Two Fundamental Legacies

The book’s most provocative revelations are perhaps Ammar’s conceptualisation of Eritrea as the paradoxical embodiment of (facile) unity and militarisation since 1890. He considers National Unity as an accomplished Fact of History.

Ammar believes that Eritrea’s success lies in the formation of “one people” out of a manageable diversity, cultural and linguistic. The Italians may have colonised the place, but their infrastructure, and administrative gaze, not to mention recomposed geography, paved the way unintentionally for a cohesive Eritrean Identity.

Militarisation as a Tragic Inheritance

It has a far less redeeming second legacy: the military thinking that has seeped into its fabric, thanks to decades of wars — fought on behalf of Italy in Somalia, Libya and Ethiopia, and later for independence. Ammar painstakingly records the enslavement of thousands of Eritreans to fight in Italy’s colonial enterprises, the obscene toll in the Battle of Adwa; he describes the mutilated askaris from Eritrea. And this martial past, he contends, lives on today as the political culture of the PFDJ state that stifles civic life and reasonable conversation in a culture of democracy. This division — unity versus militarisation — serves as the book’s overarching theme.

Colonialism and Betrayals: A Thorough, Brave Reconstruction

Underlying it is a vivid and approachable narrative of the Battle of Keren (1941) and the Italian rule’s collapse — straightforward for someone who knows nothing about Eritrean history to follow. He draws on direct historical accounts, such as Major P. Searight’s description of the carnage of battle. He situates these stories in the larger context of Eritrean suffering (which has often been sidelined or ignored in international historiography).

The book pulls no punches in its portrayal of British betrayal. Exiled Eritreans had expected that Italy’s collapse would bring justice. Still, as she records, Britain looted Eritrea’s industries and even tore down infrastructure such as a 75-km-long cableway, trading Eritrea’s future to Ethiopia and the US in exchange for military advantage. There is an excellent account of the diplomatic machinations leading up to UN Resolution 390 (A) imposing the federation.

Significantly, Passion also goes on to reveal that Eritrean aspirations were defused, not divided; the result was a deliberate act, rather than a split tendency, in its moral and political conception. That is, global powers above all refused justice again, not because Eritreans lacked consensus among ourselves, but rather for strategic interests alone & nothing more – something confirmed by the mouth of John Foster Dulles, recognising Ethiopia’s geopolitical necessity, feasibility value, over our dictum.

The Movements of the Students: A Mighty Page in the Glorious History of Non-Violent Resistance

One of that book’s strongest sections is about Asmara’s student movement (1958–68). The writer shows how a generation of young Eritreans — many of whom were literate due to British-era education and no more — formed the cornerstone of nationalist militancy. Their demonstrations, strikes and underground work played a significant role in rekindling national awakening after the imposed federation.

Ammar deftly captures shifting student politics shaped by:

- Ethiopia’s increasingly repressive policies

- Global decolonisation movements

- The 1958 general workers’ strike

- Student activism in Cairo, the home city of ELF.

Some of the students, including Isaias Afeworki and Ahmed Nasser, who would become future leaders of Eritrea, appear in these pages as student rebels forged by that same ferment.

The Age of Liberation: Complexity or Romanticism?

Ammar doesn’t romanticise the liberation struggle, but narrates the truth.

- internal ELF–EPLF conflicts

- strategic mistakes

- regional or ideological tensions

- atrocious fratricidal war between Eritrean fronts (1980/81)

- The enduring legacies of these disputes on post-independence political culture

There are also valuable primary-source interviews, such as Mohammed Ibrahim Bahdurai’s recollections of specific battles and the comprehensive retelling of Togoruba. The narratives are so helpful because they enrich the story and preserve memories, a history often long forgotten.

Post-Independence: Ghost Of The Promise That Failed

Among the most striking are the readings on post-1991 Eritrea. Ammar offers one of the most candid assessments of how the country went off its political rails, investigating: the dictator Isaias Afeworki’s centralisation of power; lack of political reconciliation being set in motion; exclusion of the ELF and other political organisations; wars with Sudan, Yemen, Ethiopia and Djibouti; open conscription and its human rights implications; the run-up to the 2001 G15 crackdown; exodus and tragedies like the Lampedusa disaster of 2013.

These chapters are not just a political indictment, but an elegy for the broken dreams of a generation. The stolen “draft speech” that Ammar wrote for the character Isaias — funny but tragic in its truthiness — says what many Eritreans wanted to hear from their own president.

Reconciliation and Unity: A recurrent Call

The theme of reconciliation is mentioned time and again in the book, advocating that: Inclusive nation-building is necessary in post-war Eritrea; the errors of the 1950s – disunity, control and forcing unwillingness should not have been repeated; Eritrea failed to take advantage of opportunities for building a democratic culture after 1991; Only a renewed sense of unity and dialogue can help to de-militarize the mindset and shake off the weight of authority: The featurs about Ibrahim Sultan, Woldeab Woldemariam, the G-13 groups (Cairo and Berlin), Hamid Idris Awate provide him enough grounds to realize the philosophical roots of Eritrean unity—roots that have been betrayed during the past several decades.

The Human Stories Profiles and Private Loss

Much of the book’s emotional weight, however, rests on Ammar’s portraits of Eritrean patriots Ibrahim Sultan Ali, Saleh Ahmed Eyay, Michael Ghaber, Seyoum [Harestay] Ogbamichael, Omar Jaber, Haile Woldetinsae/DuruE, Mussie Tesfamichael. Tesfai Teckle and Yohanne. These sketches illustrate the moral, as well as intellectual and political diversity of Eritreans who helped make history. Just as potent is Ammar’s own fragility. In the Preface, he describes how documents and notes were sadly destroyed (out of fear that they would be searched) or lost (in Beirut and Addis Ababa). Such details point to the wider tragedy: entire generations of Eritrean fighters and thinkers lost their archives, leaving holes that books like this try to fill.

Limitations

The book is history as it is, not a textbook with a preconceived order; the article format makes for some thematic duplication. It presumes a certain level of familiarity with Eritrean political groups and personalities. As Ammar concedes, lacunae in the preserved documents restrict some of these accounts. But those are picayune quibbles in view of the range and worth of the work.

Conclusion

Eritrea’s 135-Year Journey is not just a history book; it is a witness to the world and a voice of conscience. It rescues stories in danger of being lost, confronts legends that twist Eritrea’s past, and calls upon future generations to adopt unity, accountability, and reconciliation.

For Eritrea, Woldeyesus Ammar provides a gift: a historically informed (and informative), deeply felt and intellectually rigorous report on a country still grappling with its own identity. This book is essential for academics, students and Eritreans worldwide.

Awate Forum