Who Is To Blame?

Are some of the issues that are recently raised in a number of articles a tip of an iceberg, or they are tiny ripples in a cup that will ultimately vanish? Are they objective manifestations of a grim reality that some of us didn’t notice? Are they subjective issues which exist only in the minds of a few sick and hate mongering individuals as some like to say? The answers to these questions will prompt us to look into our history and probe into them deeper.

The emerging of the political parties in the late forties resulted in the polarisation of our society into two main blocks: the Andenet (mainly Kebesa Christians) vis a vis the Rabita AlIslamia (Muslims). The effect of the polarisation of the later was partly diffused by its being incorporated into the Independence Block. But the situation was aggravated by the violence perpetuated by the Andenet party and its military arm, the shifta. The gap widened even further by the atrocities committed at later stage by the Commando Forces against the lowlanders in an effort to stifle the resistance against occupation.

The dramatic change in the Kebesa’s position of joining the revolution camp besides their Muslim compatriots, after the downfall of Haile Sellasie’s regime, ushered an era of a united struggle for a common gaol. A positive development that if allowed to continue would have mended or narrowed the rapture that existed then. But the war waged by the unholy alliance forged between the EPLF and TPLF with the aim of forcing the ELF militarily out of the field (and therefore out of the power sharing process) had ended the process prematurely. That was a big set back to the healing and reconciliation process that the common struggle had initiated.

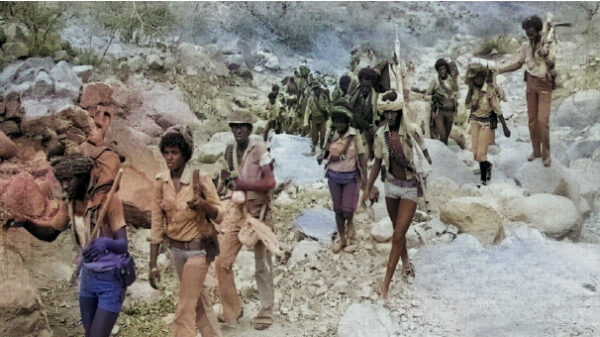

By the mid-seventies, the Muslim/lowland dominated ELF had developed into a full-fledged national organisation that reflected the diversity of the Eritrean society in its composition and all other aspects. The Muslims, in particular, invested dearly in terms of immeasurable pains and sacrifices paid in that organisation to realise a bright future for all and had a deep attachment to it. To see that all the sacrifices, hopes and ambitions going down the drain was very painful. The blow that was delivered to the ELF shuttered their hopes and aspirations towards a peaceful shared future stunned them. The ELF’s existence as a major player in the political arena would have guaranteed their rights and roles. They correctly interpreted the action of excluding the ELF as amounting to excluding them from power sharing in the Eritrea of the future paving the way for Kebesa hegemony. The campaign against the ELF was also supported by a massive psychological attack aiming at undermining the core values of the ELF fighters and their mass organisations, presenting them as cowards, corrupt, womanizers, backward—an attack which the Muslims/lowlanders perceived as targeting them. Gaim Kibreab points out that the process of weakening of the bridging of our social capital, and strengthening its bonds that was set in motion in the beginning of 1980s, among other things, as a consequence of the forceful ejection of the ELF (Kibreab, Gaim, Critical Reflections on the Eritrean war of Independence, p. 410)

The rule of Shabia was unreservedly welcomed by the Kebesa community while the bulk of Muslims were sceptically watching the situation and wishing that Shabia would rise up to the occasion and their fears would be proved wrong. They adopted a wait and see attitude giving the regime the benefit of doubt, but the regime didn’t attempt to take advantage of the opportunity and win back their trust or play down their fears and suspicions. The regime lost no time in exposing its partisan and partial nature totally ignoring their feelings. The regime went on harassing, imprisoning and purging citizens who dared to stand for their basic rights or even at a mere suspicion that they entertain such thoughts. This vindicated the worst fears that haunted the Muslims ever since Shabia’s control of power. It confirmed the fact that Shabia can never be any different from what it had proclaimed in its’ ‘Nehnan Elamanan’ manifesto. Our colleague Woldeyesus Ammar may have changed his mind now but this was his assessment in 2004. Despite this unjust and partial stand, the regime enjoyed unwavering support from the Kebesa community including those in the Diaspora. Calls made to rectify the injustice that Eritrea suffered were dismissed as Jihadist claims and smear campaigns went unabated. Suddenly in 2001, the dictatorial nature of the regime downed on its supporters and realised the facts. Such a collective change of position on the last minute when things become so unequivocally clear is not a one-time phenomenon, but a repeated of our history. In the seventies, radical Islamist tendencies were noticed among small circles of disappointed ELF. It was easily contained in its early stages as their influence had been far over shadowed by that of the ELF. The aftermath of ELF’s defeat and the break-up of the organisation resulted in a strong resentment and bitterness that overwhelmed all nationalist forces in general and the Muslims in particular. That condition that created a fertile ground for the Islamist organisations to emerge and fill the vacuum that was left behind and they enjoyed a popular support that didn’t have before. It was the first time that the Eritrean political Arena witnessed the birth of organisations indoctrinated with Islamism.

Who is to blame for that?

Is it Shabia’s adventurous, and its insensible and irresponsible policies had failed to strike the right balance for between the interests of the stakeholders, or the Muslims that found themselves suddenly forced out of the political equation in an attempt to reassert their position they had to try even non-traditional methods and walk in an uncharted territories?

The Islamists appeared at a time when the Muslims badly needed any helping hand that would draw them out of the deep despair they found themselves in. Some Muslims viewed the Islamists as a new champion that can defend and advance their cause and as a proper response to Shabia’s extremism. It is clear to me who should bear the responsibility and the blame. I lay the blame on the shoulders of Shabia.

The regime’s propaganda machine exploited the new phenomenon and relentlessly propagated fear and lies about the danger that the Islamists pose to the existence of Eritrean Christians. It portrayed itself as the savoir and the defender of Kebasa Christians’ interests in the face of the advancing (presumed) Jihadist menace. Thus it rallied the support needed for its unfair and aggressive policies that it carried against Muslims and all nationalists. The regime took a Crusader’s role by riding the unsaddled and unbridled horse of the ‘War On Terror’ that Goerge Bush, the former USA president, sponsored. It offered its unconditional services and voluntarily invited to play the role of a loyal regional agent. To prove that it really meant business and to improve its credentials for the job, it severed the diplomatic relations with the Sudan under the pretext that the later was exporting Islamic terror to Eritrea and the region. Locally, things went so far and considered any Eritrean Muslim practicing his religious rituals and frequenting the mosque, or wearing a beard, as Jihadist collaborator. Those citizens were not only suspected by the security forces of the regime, but also by their own compatriots. Islamic religious schools (Maahad) became the main targets throughout the country. Teachers were abducted and imprisoned; their whereabouts are not known until now. There are reports that they have been summarily executed. No Kebesa intellectual or human rights activist have talked about the matter then.

The system has not spared any provocative measure or acts of infringement that it has not applied against the Muslims. Finally yet importantly, is has embarked on a forced settlement and land redistribution program.

In normal situation, people have moved around and settled in different parts of the western lowlands; that had never been a problem. The host population are friendly, hospitable by tradition. This coexistence was based on an informal and mutual understanding. The guests acknowledged the rights of the host, particularly that of land ownership and respected the norms and values of the host society. In return, the newcomers enjoyed a peaceful life and were granted land to live in and farm including assistance that they required. It is contrary to the current resettlements program that is based on the regime’s policy that considers the lowlands as no-man’s land. Thus, the land grapping and the establishments of new settlements are no more considered encroachments into the rights of the local population by the regime and its apologists. But this policy destabilises the pastoral way of life and norms of the host society and creates antagonistic feelings and frictions between the now unwelcome settlers and the original population. Imposing settlements of such a large scale, disrupting the way of life of the local population, not recognising their rights, and expropriation of their ancestral land is a crime that the state is committing under our very nose—that should at least force us to condemn it unanimously. This fact has exasperated the already tense and polarised situation.

The current articles that deal with such issues are serious attempts by concerned (or directly affected) citizens who are voicing their views and grievances, and trying to draw the attention of the silent majority of our partners in the nation. Their purpose is not to instigate hate or demonise a certain society as is wrongly conceived by some. It is a sincere call to all of us to assume our national responsibilities and stand against all forms of injustices.

The people who are still unable to see the looming dangers hanging over us, have either lost touch with the reality or are acting like an ostrich that buries its head in the sand when faced by an imminent danger. Like the proverbial Ostrich, some believe everything is safe so long as they don’t see and hear what is going around in Eritrea. Some would also try to make excuses for their inaction by stressing the fact that no one has power to make a difference except the regime. The excuse goes, no one should be blamed except the regime which all of us oppose. What is really needed at this moment is an honest acknowledgment of the fact that the current situation is an accumulative result of historical injustices that have not been properly addressed. Let us declare our readiness and good intention to seek appropriate solutions together.

The assertion that the dictatorial regime is solely responsible for all that went wrong, and that its removal will automatically undo all the injustices, is a gross over simplification of a very complex problem. It is also self-deception and delusional. At least we should recognize that some of us helped in creating the regime and we let the Jini out the bottle.

A popular Egyptian saying clearly applies to our case: ‘Min faraanek ya faroon’ Oh! Pharaoh who made you so devious the way you are?’

The Pharaoh replied, ‘You, the people.’ Meaning, no one objected to the Pharaoh’s wrongdoing until it was too late.

No one wished for things to take such a critical turn and no one would benefit from pushing things to the edge. If we are concerned about safeguarding our national interest of our country as a whole, which is nothing but the sum of its components, then we are required to be equally concerned about the interest of each of our country’s components. National interest cannot be fully safeguarded when an interest of a certain group is not.

Awate Forum