What (Italian) Colonialism Did To My People Of (Eritrean) Kebessa

[Editor’s note: We usually try to limit article lengths to 5-7 pages, and when a piece is longer, we will usually serialize it. But then, there are some articles that have to be read at one sitting…preferably printed, preferably on a lazy Sunday morning. This article by Aklilu Zere–all 26 pages, all of the nearly 13,000 words– is one of them. Enjoy, and see you in the comments section.]

________________________________________________________________________________________

“Suffering is by no means a privilege, a sign of nobility, a reminder of God. Suffering is a fierce, bestial thing, commonplace, uncalled for, natural as air. It is intangible; no one can grasp it or fight against it; it dwells in time / is the same thing as time; if it comes in fits and starts, that is only so as to leave the sufferer more defenseless during the moments that follow, those long moments when one relives the last bout of torture and waits for the next.” Cesare Pavese Quotes

The Name

Before the Italian invasion and imminent capture of Eritrea the highland had many names but local historians always disagreed on those names. Some historians said the name was Mereb Milash, “This side of river Mereb”, a river that now divides Eritrea and Ethiopia. Others said the name was Midri Hamasien, “the land of the Hams”.

The Italians did not bother to consult the people when they named their colony, Eritrea, though to their credit they named the new capital city they intended to build, and eventually did splendidly, Asmara, a word taken from the four villages that existed in that area when the Italians arrived. The villages were collectively known as Arbate Asmara.

The Italians took the name Eritrea from the Bible [some say from the Greeks], the biblical name of the Red Sea. Its effect on the monks and the women was immediate: they liked and adored the name and did not waste time using it.

In the highland if the monks and the women did not mind, every one else would not mind. The problem was with the sounding of the name. The pronunciation came in all varieties and forms of sounds: Eltra, Eritra, Elitrea; Eritrea; Ertra. But people didn’t mind, they just said what came to their mouth and said it proudly. It was unconscious, so no shame was attached with the sounding of what they said.

The monks liked the name Eritrea because it was in the Bible and referred to the very important event they preached and cherished: the crossing of the Jews through the middle of the Red Sea led by Moses to Mount Sinai and to freedom from slavery.

Arms Length Acceptance

At the beginning it was not the look of the Italians that bothered the monks and thus the women. In Eritrea there were Eritreans with very pale skin, pale faces, straight noses, thin lips and soft hairs so the white skin was not absolutely something new or strange. So was the hair. The language was also not a concern for the Monks and the women who literally believed in the story of the tower of Babel, that God gave people different tongues. It was also good for the monks who did not want any rapport between the Italians and the people, because they knew direct communication always leads to understanding that leads to tolerance and eventually influence. No communication meant every one kept his own values. In a nutshell, it was the religion of the Italians that bothered the monks: the Italians were Christians but not “real” Christians.

Out of many the two fundamental values the monks wanted the people to watch out were the dietary rules and the printed (revised) Bible. In due faith diligence the Monks dictated their followers not to eat anything the Italians touched or handed, even in time of scarcity, and not to touch any printed Bible lest they face excommunication exactly as they did with the Swedish missionaries.

Special warning was also handed specifically to the women concerning sugar, sweets and bleached wheat flour which the people call fino. The Monks said the Italians might use the power of sweets and bleached flour to woo first little kids and then eventually the women.

The monks knew the women were the pillars of the faith. A convinced woman was an iron curtain. But they also knew women fight for survival. What would the women do if draught or locusts destroyed their yields and the Italians offered something? Would they say no and forgo survival? Or would they succumb to their survival instinct and diminish their faith?

The monks were wise and creative. Like they allowed the woman to have coffee, sensing the hardy highland woman had her share of weaknesses, they also allowed her to take flour from the Italians but only if she was in dire need. But to the surprise of the monks and more to the Italians she refused to touch the flour and instead she asked for grain to grind herself which the Italians happily provided.

As for the sugar, against the advice of the monks, the woman did not refuse the opportunity to take if the Italians offered and started using it to sweeten her bitter coffee.

The monks were not worried with the flour or sugar, for they knew they were harmless. Their biggest worry was the Italians might use those as baits for conversion or worse influence new eating habits that transgressed the Church rules. So when the woman stuck with her faith and values albeit using sugar, the monks celebrated like nothing before and their trust towards the woman was cemented forever.

The men were not of too much concern for the monks because they knew men would err, but would eventually come back to their faith, the faith of the woman that raised them in her back and her lap.

Italian Attitude To Women

Italians of now and Italians of then, loved and respected women. Though they came as colonizers, they never went out of their way to harm or upset the women. Actually the Italians found the women of Eritrea resembled their mothers back home in character and behavior.

Those few Eritrean girls who were hired as maids, quickly adapted to their new surrounding and to the amazement of the Italians quickly mastered the language and were also quick learners to any task showed and assigned to them but initially they would not touch the Italian food; would not sleep in the house and the only things they willingly took if given were sugar, soap and fabric.

There were three things the Italians brought that made the hardy woman always remember and remain grateful to them: the flour mill, soap, and shoes.

The introduction of the mill signified her emancipation from manual grinding, a tedious, painful and non-ending back breaker. Because manual grinding was time consuming, the mill also freed up time for her to rest or do tasks that otherwise was set aside due to scarcity of time.

Soap not only made cleaning clothes easier but also for the first time it enabled her to look after herself. As for the shoe, she took it as something that came from heaven like Manna to save her from that dreadful thorn of curse.

The women used to use Shibti as detergent, a very fine white seed from a plant that grew along side streams. But due to its scarcity and seasonal availability she could not use it through out the year. When the Italians introduced soap which they call “sapone” the women took the word literally and called it Samna. Everything that cleans became samna, even the powdered detergent called Omo became a universal detergent and not a brand name. Until today the woman, whether in Eritrea or abroad calls any detergent Omo. That was how she was attached to it.

Women of the highland loved white fabric, and would die for it if it was emblazoned with flowers. They had special word for it: tsada mdru ms inbaba. Knowing this, the Italians started importing fabrics so the women could buy them for clothes. Until recently, the first item a bride-to-be orders her groom-to-be is a white fabric with flower design.

Italian Character

For the Italians, Eritrea was their first colony. So as soon as the colony was established many civilian Italians, some volunteering, some adventurous and some who were forced because of their political tendencies came to Eritrea. All of those civilians had some kind of skill they brought with them from Italy and immediately ventured working in their field of expertise.

Italians are compulsive and sentimental people. If given the opportunity, they prefer to stay in their home country until death. If not, they would emulate everything they know to their new surroundings; in other words, they recreate little Italy everywhere they go. If they did this as immigrants, imagine what they did as colonizers.

Mutual “Mellow Disdain”: A Working Relationship

Comparing to the British, French, Spanish or Portuguese colonizers, the Italians were naïve and inexperienced when it came to colonizing. As soon as they declared Eritrea their colony, the Italians started transforming the landscape emulating their homeland. They poured their skills and hearts with no reservation because they thought their stay was forever. They built villas, roads, rail ways, bridges and tunnels, not only artistically, aesthetically and architecturally beautiful but also durable that still stands. The Italians did this by using their renowned architectural engineering acumen and using the best ingredients which the highland is abounds with: granite stone.

As colonizers, every Eritrean labor was free to the Italians. At that time the attitude of the Italians towards the inhabitants could best be described as mellow disdain. But to their credit, to who ever showed willingness to learn, they trained and mentored as if their own kin. The disdain was mutual. The inhabitants disdained the Italians; some say mainly due to the unfinished open waste management system that bisects the city in half and rendered it smelly and dirty looking. The area was called Mai-bela because there was a stream that runs through it. (The good woman in my house says she would have absolved Nsu had he utilized the slave labor to build waste management system in all cities and towns of Eritrea).

Despite their meager resource, rugged surroundings and history of isolation the people were stoic, intelligent, curious, dexterous, and easily trainable. They were also gifted with high memory retention and good common sense.

To the astonishment of the Italian colonizers, in no time, many Eritreans became masons, brick layers, carpenters, mechanics, machinists, drivers, train engineers and chefs. They excelled in any field that required dexterity and imagination.

As for the Italian language, any Eritrean who came in contact with an Italian for any given time, left understanding and comfortably speaking the language just like those who learned to cook Italian foods became good at cooking Italian recipes.

In the nineteen twenties, Mussolini started banishing avant-garde Italian artists and architects to Eritrea as means of punishment. Those Italian rebels took Eritrea as blank canvas and started to experiment their ideas with astounding results, especially in the field of architecture and fashion designs. Because those artists were enemies to Mussolini, not only did they openly interact with the inhabitants but some even married the hardy but pretty Eritrean maid and in defiance to the Fascist racist ideology openly and willingly trained local apprentices.

The Eritrean apprentices did not disappoint. They paid back for their fortunes by building magnificent churches and mosques in the villages and made the Monks, The Sheiks and the women happy and proud.

Those who apprenticed under Italian tailors started tailoring garments for the inhabitants, mainly the women, and for the first time the women started wearing beautiful designed and custom tailored white dresses, which at first dismayed the monks, but eventually relented for they knew superficial look had nothing to do with the strong heart and strong belief of the woman.

The Hardy Kebessa Woman – Diet

The monks were right. The sugar, the mill, the soap and tailored dresses had no effect on the woman’s values and beliefs. Yes, they made her look beautiful, clean and rested, but in what mattered, she stuck to her tradition.

She continued drinking coffee brewed in her own hand crafted clay pot that she called Jebena and not in metal pots like the Italians and unlike the Italians, she drank her coffee black even though she could have added cow’s or goat’s milk. If she did not have sugar, almost always, she used salt or drank it black.

She avoided touching or using the Italian flour. Even though she heard mouthwatering talks about pasta, she avoided it like it was worm, the warm that caused pain in her children’s stomach. As for pork meat, what she called Siga Hasema, the only time she used it was when she fed a piece of salami to her kids because it was believed it protected them from evil spirits.

Industrialization

Among the Italian colonizers there were individuals with business acumen, who looked forward rather than their state quo condition and as business minded individuals race, skin color or class status of the inhabitants was immaterial to them. Also deep in their heart they knew the Fascist regime in Italy was going to be defeated. Many of the Italians in Eritrea whether soldiers or civilians, had already made up their mind to stay in Eritrea, no mater what the fate of their mother country became.

Some Italian entrepreneurs had positive appreciation of their colonized Eritreans. They had observed the character, work ethic and easy adoptability of the people and had determined that transformation was imminent. They were also impressed with the behavior, discipline and directness of the women, which closely resembled that of their mothers. They observed that even though the woman would not compromise on her faith and village values, she was open to modernization.

Without delay, Italian business men started opening myriad of businesses that catered the immediate and future needs of the inhabitants and those Italians who were adamant to stay in Eritrea. What started with the introduction of grain mills and importing soaps to help the plight of the woman spread to actual manufacturing it locally.

Signore Baratolo opened textile factory and started churning white fabrics with myriad flowery designs mostly inspired by the local women; Signore Moliniery opened marble shop, some for export and some for local usage and found laborers happily working with the familiar stone; Signore Bini opened shoe factory, which became the most profitable of all the companies and also got mouthful blessings from everyone but more from the woman; the Luigi family opened soap factory and they always remained in the head and heart of the woman; the Fenili family opened winery, though the locals never got use to wines but at least city men found an alternative to the boring local beverage they called Swa [if a Swa or aptly to say tsray is good they called it Chianti– a fine Italian wine); an unknown family opened cigarette factory, which was cursed by the monks, but to no avail; Signore Mario opened candle and match factory and got hearty blessing from the monks and the women; Signore Denadai started banana and orange plantation mostly for export to the newly rich Arab countries; the Melotti family started beer company and were not disappointed despite the monk’s and the urban woman’s outrage; the V. Costa family opened machinery shop and to their amazement many of their apprentices became expert machinists and coach builders and in no time local made buses started roaming the roadways; the Salinas family started salt manufacturing company for export because the woman would not touch manufactured salt. She just continued buying salt delivered by camels; the Alfa family opened bread and cake factory; the Merenghi family opened glass manufacturing company because the land was rich in silica, soda and lime.

Culture Clash

There were two companies that drew the most scrutiny and attention and later violent reactions from the monks. One was Incode, a meat company, owned by the hated Giovanni brothers and the other was Salumificio Torinese, salami and Cheese Company.

The Giovanni brothers opened a slaughter house and hired local people for the task. The laborers were harassed and threatened by the monks until finally out of fear they hid their face so no one could identify them. They became nameless and faceless in their own homeland and would not tell even their immediate family what they did for living. They were big and muscular probably chosen for their physical attributes but also could be due to the meat they consumed.

It was told the Giovanni brothers did not mind the butchers eat as much meat as they wanted as long as it was done discretely within the slaughter house perimeter because they were weary and afraid of the monks.

Every one run away from the meat packers if saw them during distributing meat to the Italian owned groceries called negozio. They could see cows’ blood splattered all over their large leather aprons, hats and even their faces. Children were told the butchers were child eaters and were advised to run away as fast as their skinny legs could handle. The butchers knew they were not liked by their own people but it was not secret their masters treated them well. So despite their treatment by the people they remained faithful to their job albeit unknown and unrecognized by their own kind.

Salumificio Torinese was a company owned by group of people so no one could point finger to an individual owner. Its main products were pork meat and pork products like sausages, salami bacon and cheese. It had its own pig slaughter house located in the central bus station called Shuk by the inhabitants.

For unknown reasons, the wall facing the bus station has big glass windows easy to see through. One could easily see from near or far the initial slaughtering process that comprised pushing the pig through a slippery incline to a boiling pool of water. What passers by saw was a splash of water and steam but it was what they heard that pierced their heart: a haunting scream of death followed by silence.

Women who witnessed this would hold their head and lament “Iwiy, Iwiy, intay geratom iya izom rugumat”, followed by “akedimom ke zeiy ketliwa” which meant “ what did the pig did to them, those rascals, at least they could have killed it before pushing it to the pool of boiling water”.

For the monks, the open display of the abominable process of slaughtering the pig (to begin with- unclean animal) was a sign of arrogance and cruelty to animals and in itself was sufficient for their people to avoid pork so they did not have to elaborate like they did with the beef company.

Little Italy

Not to be left behind, some urbane Italian business men opened movie theaters and named them after their favorite memories: Cinema Impero; Cinema Roma, Cinema Dante, Cinema Capitol, Cinema Croce Rosa, Cinema Odeon and Cinema Hamasien for the locals. The Monks and women were terrified with the concept and spearheaded Crusade that ended in stalemate.

The remaining urbane Italian business men opened hotels and inns and named them with names that signified their homesickness: Albergo Ciao; Albergo Italia and many more.

Still others endowed with entertainment disposition opened bars and cafes and named them after region they left behind: Ristorante Capri; Bar Torino; Bar Corso; Bar Royale and many more. Not to be left behind, the Roman Catholic Church with all its glory and authority started building magnificent churches and named them after its favorite saints: Cathedrale Santa Maria; Chiesa San Francesco; Chiesa San Antonio and many more.

The Delay Of The Colonization Project

Italians, though naïve when it came to colonizing, were not outright benevolent to the people of Eritrea. They could best be described as confused colonizers.

Eritrea was a launching pad for their further ambitions: to colonize Ethiopia, Somalia, and Libya. But they found the Eritrean landscape overwhelmingly similar to where they came from and for moment were taken aback and delayed their mission. Their innate character of building artistic things temporarily clouded their colonial aim. As soon as they claimed the territory, unlike the British or the French, brought their cream de la cream experts and with no expense to spare, started transforming the land to look like Italy. Because they were in a rush they were not treating the local laborers as colonized people or slaves but as semi-Sicilians. Mind you, the leaders starting from the Generals to administrators were Northern Italians and as per their request many Sicilians were rounded up in Italy and sent to Eritrea to labor along side the inhabitants.

The Hardy Kebessa Woman – Buses

The Introduction of buses and trains was mixed blessing to the monks and the woman. They were comfortable and time saving, no doubt about that, but the woman took time to adapt because she was not sure whether riding on buses or trains violated her faith. The monks were also ambivalent to riding on buses or trains for they abhor easy life or any luxury.

Finally the monks decided not to ride themselves but allowed the woman to ride. No one knew why they decided to allow the woman to ride but some say it was based on past history and practicality: you give small you receive big. The monks knew the woman was curious and likely to fall victim to her curiosity. So rather than let her fall into temptation, if they allowed her to ride, they will gain her trust foe ever.

When the monks declared riding was innocuous so admissible, all women could not wait to ride and as soon as they got opportunity, many did. But they paid the price. As soon as the bus or train started moving, the earth and trees around them started moving at a speed that eventually disturbed their humble and unaccustomed brain and created disequilibrium with unsavory results: vomiting and headaches.

Not all women suffered from motion sickness, but at that time no one knew it was motion sickness. Those who suffered the sickness started blaming themselves for committing sin by riding on bus or train. Those who didn’t get the sickness suffered from anxiety of anticipation to the sickness. The Monks had no answer and they were not ready to recant the rule they sanctioned that allowed the woman to ride.

It was chaotic and in chaos myths were born. Many blamed the Italians and said “They brought the bus and the train to kill us”. But this was refuted because they saw the Italians themselves ride on their own buses and trains without getting sick. Some blamed the smoking drivers and said “while he was smoking, he let Satan drive the bus”. But to their dismay the myth was refuted because even if the driver did not smoke some women still got sick. Some mythical solutions were also born. The most popular was “close your eyes while riding”, and “never to eat eggs” (as if they have the luxury to indulge in eggs), to which many tried but failed to avoid the inevitable. Some said the smell of lemon could cure motion sickness, so every woman brought lemon before the ride. To their surprise the lemon scent combined with the cigarette smoke exasperated their condition. Others said, riding on empty stomach was the solution. To begin with, those women did not eat much, but to alleviate their anxiety they rode in an absolutely empty stomach. Some got better, others worse. Those who were affected worse reverted back to their old life style: walking on foot, no matter how far or how tiring. Some persisted by saying “Ane Do kab kusto yhamik iye”, meaning “I am not weaker than so and so” and despite their sickness continued riding and eventually got better. Time and experience teach and as time passed the sickness was taken as affliction that affected few and those affected were pitied but not discriminated.

Apartheid & War

After thirty years of living together as strangers, one cosmopolitan the other rural peasant (because the Italians never mastered the art of colonizing thus did not act or behave as colonizers) the Italians changed abruptly because a new decree of apartheid was decreed by the fascist regime in Italy. The decree was lengthy, detailed, and cruel and encompassed every facets of life of the inhabitants.

The first people affected by the directive were the conscripts and the laborers. At the beginning the Italians had their soldiers, all Italians and mostly from the south, and were not keen to conscript Eritreans. They had Eritrean laborers who worked in the military camps as cooks and cleaners but none in the army. The laborers always told good things about their treatment when working for the Italians and complaints were rare. The Italians liked the laborers because the laborers worked hard, were honest and direct and above all had mastered the Italian language and habits in no time that greatly amused and pleased the Italians.

When the Italians, thinking they were as smart and courageous as their Roman ancestors, went alone to invade Ethiopia they paid high price in defeat and bore historical embarrassment. They became the first European nation to be defeated by an African nation.

They learned their lesson well and immediately started conscripting Eritreans for military services. The numbers were unknown but they managed to conscript and train enough locals for the second invasion. They found the locals not only eager to learn but also fast learners and courageous. In no time the conscripts learnt to handle armaments, listen and follow instructions and other military requirements. To the delight of the Italians, on their second trial they were easily able to successfully invade Ethiopia and put the country under their control. The locals contributed not only their life but also excellent knowledge of the land due to similarity of landscape and were mostly the ones who were deployed at the front. They also spoke the Italian language fluently.

Coincidentally it was during the second invasion that apartheid was decreed and the Generals did not waste time enacting it in the army as their civilian counterparts did with the local population at large.

So during the second invasion of Ethiopia the local conscripts were segregated from the Italian army personnel not only physically but also were treated as undesirables and supplied with meager rations and old armaments. Whereas during the first invasion the Eritreans who were hired as laborers to serve in the army as cooks and cleaners had only good things to say about the Italians, many of the conscripts felt betrayed and for the first time started to see the Italians not as harmless strangers but as dangerous foreigners. Many conscripts fled from their assignment and many joined the Ethiopian rebels and played key roles in liberating Ethiopia from Italian rule.

Many of those who ran away returned to their villages and became rebels and started inflicting harm to the Italians. Even those who stayed as conscripts daringly started confronting the Italian officers and demanded equal treatment. If refused they took violent actions.

One of the stupid rules of segregation was to serve the conscripts tea or other beverages in recycled soup cans and not glass or ceramic cups. For some reason this offended the conscripts more than anything else. Many conscripts took the hot beverage served in recycled soup cans and splashed it to the face of any Italian they encountered. Those who were caught were summarily hanged or shot.

Many Italian soldiers’ heads were also cracked some even died by stones thrown at night or in hiding. Seeing such daring rebellion, the Generals amended the decree and started treating the few remaining conscripts in dignity and deference. But it was too late and in five years the whole Italian army was defeated and all surrendered to the British led army. One favorite say of those conscripts was “Italians may be good lovers and eaters but were not good soldiers”.

In the City, what most upset the locals was their restriction not to walk through the main thoroughfare which the locals call Combishtato, a beautiful and super modern Boulevard. The decree stated that only whites could use the thoroughfare. Many locals did not care and started walking in defiance but paid the price in imprisonment and torture. For the first time the people started to see the Italians as enemy.

Many Italians were unhappy about the apartheid but were helpless opposing it openly. Some Italians secretly joined the local resistance and played big roles in weakening the system. Apartheid was short lived in Eritrea and was soon forgotten as soon as the British defeated the Italians. Many locals felt pity to the defeated Italians and never harassed those who chose to stay in Eritrea. And not only did many Italians stayed, some even returned back from Italy to live in the land and people of their used-to-be colony, Eritrea.

The Hardy Kebessa Woman – The Maid

After living with European strangers for quite a while change was inevitable to Eritreans. What was reserved and preserved in isolation for generations started to show signs of budding.

The first visible change happened to the least likely entity, the woman, and to be precise the maid. The change was likely due to close relationship with the Italian households she served.

The monks already predicted that would happen so they were closely monitoring the maid’s faith, her behavior and her activities by themselves and through others like how often did she attended church? Did she strictly follow the fasting rules? Did she refuse to participate in the eating habits of the household she serviced? Did she cover herself decently? Did she maintain regular contact with her mother and her village church and many more? In those respect she did not disappoint. She even exhibited more conservative attitude toward her faith and traditions.

Of course, she mastered the Italian language so she started inserting Italian word here and then when she talked with her own kin. Of course, she gained weight and looked plumb. Of course, she looked extremely clean and she was sometimes seen with her long polished nails and painted lips. Even her wardrobe changed. She started wearing clothes given to her by the Italian woman she honestly served and people were amused to see one of their own clad in Italian clothes. The clothes were fancy but not flagrant for the Italian woman of that era was herself conservatively dressed. The shoe was another thing. The people started wondering how she could walk on those shoes. But she did. Of course, she was awkward at first more to do with shyness rather than the style of the shoe, but through repetition she was able to overcome shyness and also perfected cat walking in high heeled shoes.

The Italians loved her for she was honest, direct, easy learner with excellent memory retention but above all what impressed them was her strong belief in her faith and tradition. They might have tested her if she was to be trusted. What they did not know was her mother and the village women incessantly taught her not to touch what was not her’s (Zeinatki Aitelili). Also she was taught not to take what was offered to her (SK ilki zihabuki aitkebeli). The Italians knew a normal mortal person especially who grew in scarcity could easily succumb to the smell and taste of Italian foods or other goodies but not she.

To help her preserve her beautiful and white teeth they offered her brush and tooth paste but like to everything that she was not sure of she declined the offer (until recently the majority of Eritreans believe tooth paste is made from pork products) and stuck to her twig which she used as brush and tooth paste in one called mewetz. The highlanders preferred a twig from a lemon tree or olive tree. They break a pencil size twig and chew at the end of it until it bristles and then brush their teeth with it. The fluid in the branch acts as antiseptic that killed germs in their mouth and also kept their beautiful teeth white and their breath fresh.

The Italians, thinking they were more advanced than her and her people, would not use what she used even though they suffered with dental problems more than her. But in recognition and reward to her admirable behavior they planted lemon and olive trees in the city and everywhere in the highland so that she in particular and her people in general would have easy access and availability.

She learned and excelled in Italian cooking but would not eat it. She even experimented to spice their food and they liked it. Where as before their pasta and lasagnas tasted bland, she added the local spiced ground red pepper they call Berbere and some other spices and made them palatial and tasteful. Every time she made new menu, a mixture of both cultures, they just gorged it and talked about it.

But above all what the Italians liked about her was her extraordinary cleanliness, discipline and honesty. She did not forget what her Mother and village women taught her when she was growing up. Her memory retention came from the incessant advice she got from her mother in never to forge what she learnt lest she embarrass her family and village. The incessant training from the women was always followed by a knock to the shoulder (a knock to the head is reserved for the hard headed boys) if she forgot. The tool her mother used to discipline her was a wooden spatula she called Mekhos and in rare situations raw hide called Miran. So if the girl forgot to put exact amount of salt, she got a knock on her shoulders. She was also trained on myriad of etiquette on how to sit; how to stand; how to sleep; how to talk; how to use the shawl; how to make fire, and many hundreds more. All the training made her malleable, trainable, creative, innovative and confident.

She was also lucky not to be coward. In that hardy place cowards did not last long. She was trained equal to the boys, not to be coward; not to be afraid to say the right things; to be ready to defend her-self in case of danger, natural or human. While growing she was not scared of hyenas for she was charged with looking after the family goats; she was not scared of snakes for she was trained how to incapacitate a snake. She was as good as the boys in using stone for defensive or offensive purposes.

It did not take the Italian families long to know her daring character. If she said no it meant no. One unique trait of Eritrean woman was she does not repeat. She said what she wanted to say once and that was it. No one could nudge or convince her to change what she said.

The Italians really respected and admired her. No Eritrean maid was treated as servant but a member of the household, half credit to the Italians but half credit to the maid because at no circumstances would she consider herself an inferior being. She became a legend and her legend grew because the news of her character travelled all over Italy and there any one who could afford wanted one. Later in the late fifties and sixties even the newly rich Arabs wanted her service and compensated her handsomely. Where as the Italians wanted her to be maid and baby sitter, the Arab kings, emirates, and princes wanted her to beautify, train and mentor their wives and daughters.

She was also beautiful and warm-hearted. One thing that worried the monks was she occasionally let her hair loose, not braided. She had long, shiny, smooth, soft virgin hair. When her hair was liberated from bondage, and she started oiling it with Italian made hair pomade it just grew longer and looked richer.

For the monks, loose hair was too much and they started applying indirect pressure through her mother and village women and finally relented with a twist. The Italian woman taught her some hairstyles that involve simple braids and when she did applied it to her hair it was accepted as a compromise by her mother, the village women and even the monks were not adamant. The monks always compromised with the woman because they know her heart.

The maid also started revolutionizing the local cooking. By then her knowledge of ingredients have expanded, because those Italians who employed her knowing her dietary restrictions helped her expand safe ingredients she could use. She started to sparingly add sugar to make Himbasha; instead of spiced butter (zitekelese tesmi) she started using olive oil; she also added exotic spices to make the powdered chickpeas they call Shuro and it never tasted bland again.

Her biggest contribution was in helping building new churches in the cities she dwelled. All cities were newly built by Italians. Before Italy, Eritrea was a land of villages. Every time they built a city or town, the Italians built their own churches, Catholic churches. The maid could not attend Catholic Churches so she was forced to walk long distance to the nearest village to attend church services which were held daily. She was always tired, even though she could not say it for she was told by her mother never to say dekhime.

The solution came from all the laborers and maids who lived in one city. They approached the monks and proposed their idea of helping to build churches. This idea was double blessing for the monks and encouraged them to proceed. The laborers and maids raised enough money and because by then there were good local builders, the churches were built in no time. Every one was proud and happy but especially the women and the monks. What elated them was the church was built with local stone; by a local hand; with money raised by the laborers and the maid who trusted and was trusted by the eternal monks.

Priests and deacons were allocated by the monks to run the churches. Every village had its saint and the village church was named after the saint. But because the maids came from different villages they asked the monks to name the churches which they happily did. The maids consulted the monks for naming a saint in order to avoid conflict among themselves.

Women of the highland abhor conflicts and competition among themselves. All women in that hardy place were raised not to compete against one another. They united and made miracles happen. With meager resource and hardy place mere survival was miracle in itself. Unity devoid of competition also made the women strong with meaningful power. But they never abused their collective power. They only utilized it to enhance the survival of the village and their church.

The Eritrean Man

At the same period and just like the maid, the men who labored under the Italians also started exhibiting changes. Those men were the gardeners, the cleaners, the cooks, the guards, the drivers, the train engineers, the masons, the mechanics, the brick layers, the repairmen and the conscripts. Most of the changes were on personal habits but most remained true to their faith and tradition.

Unlike the maids the laborers were not treated kindly or with respect. They were exploited. No matter how good, intelligent, easily trainable they were, their efforts and achievements were most of the time ignored by their Italian masters.

For the first time in their life the men started to feel inferior and weak. Once a man left his village and start living in towns and cities he was exposed to competition with other men. He felt he was caged and manacled because he was living in congested quarters and not in open landscape like in his village or his land. Fighting against other men became habitual. Some men started to drink heavily; some others developed smoking habits.

Once the man sinned, he felt his betrayal to his mother and village and succumbed more towards destructive behaviors. Some men started betraying their wives and beating them and their kids, unknown and unheard of behavior. The monks condemned the behavior to no avail. Beating and cheating their wives became contagious and which started with few spread to many. Only the threat of excommunication and threat from the woman’s family cooled the habit. Many reformed because the acts and the actors were shamed.

The village woman was not very fertile. This was due to scarcity but mostly due to her strong belief in abstinence. Circumstances changed in the cities and towns. The availability of better food and health services combined with less work to the woman but above all because her power was diluted and her opinions rejected (her “No” fell into deaf ears of the man) resulted in her having many children against her wishes and belief in abstinence, which in turn created chasm between her and the breadwinner, the husband.

Where as in the village both men and women toiled, with the man’s tasks being seasonal, short and limited but hers throughout the year, long and unlimited, there was a recognition of her efforts and she was given respect and freedom to decide and manage her family, the village and her church.

In the cities and towns, except the maids, it was the man who was the sole provider for the household and started taking advantage of his newly acquired power to belittle and denigrate the woman. He totally forgot where he originated and his tradition and started emulating the colonizers power over him to his wife and kids. He wronged her mistakenly because no matter what he did to her she silently soaked it but continued the tradition and faith she learnt from her mother and village women. Physically and mentally the highland woman was stronger than the man but she never abused her strength. No matter how he abused her, she hid the abuse from her kids and raised them the way she was taught to raise kids.

The Hardy Kebessa Woman – City Life

She was not passive. With the neighboring women she established close knit community that resembled a village and continued the tradition she learnt when growing. She visited her village many times a year sometimes to her family and her village people other times during weddings, funerals or visiting the sick. So she did not feel alienated. The biggest event for her visit was the pilgrimage, Ngdet, done once every year to her village church. She prepared for that day months before and it was a day that her whole family went together.

She initially hated the city because she felt captive living in close quarters with people she did not grew with and the lack of privacy especially during call of nature. The small brick house caused claustrophobic reactions she never knew she had. The tin roofs kept her awoke during nights when it rains or when the pigeons performed their singing and dancing rituals. She felt suffocated in summer during unrelenting heat. She felt naked and helpless if strong wind carried away the tin roofs. She developed phobias against things made of metal which she named zingo.

Out of all those inconveniences there was one practice that almost drove her crazy: shutting the doors of her house. In the city, people shut their doors and she had to follow suit because she heard scary tales. No one shut their doors in the village. Only an abandoned house remained shut or houses belonging to dead owners. To shut a door in the village was a sign of wickedness.

But all those were temporary setbacks. Due to phobias caused by the tin roof she avoided using anything made of metal and stuck with her clay pots. The clay also reminded her of her connectedness to earth and her village. Against the maid’s highly recommended aluminum coffee maker, she adamantly stuck with her own hand made clay products: Jebena ; mogogo; tsahli and many more.

There were two things she did not mind in the city: water and wood for fire. Tap water liberated her from that grueling daily task of fetching water in her back. She also had to no more to fetch wood.

Of all the tasks the woman performed while growing up none can compare with the dread of fetching water. Water was scarce commodity in the highland. The only source of water was a flowing stream that all surrounding villages use and was always at the bottom of valleys and far from the villages. It involved descending and ascending steep and ragged hills that involved careful negotiating dangerous and hazardous rough tracks, very difficult task even without a load.

She used clay jar she made herself called Utro. She fetched water once daily either at down or in late afternoons. She always joined other women when fetching water because loads feel lighter if the mind was distracted by laughter, Tsehak; songs, Derfi and chats, Zereba with others.

She won’t fetch water at other times especially at dark or mid day due to superstitions that stipulated those hours for the fairies. She was not scared of fairies but she believed in fairness, so she left those restricted times for their share of use.

She was taught to have water at all times because in that land somebody, be strangers, kids or others will ask for cup of water. She might had felt sad if she was asked for bread and said she did not have but to say she did not have water made her felt sinned.

She never believed that tap water won’t dry like the seasonal stream she knew, so she stored tap water in her clay jar she brought from the village. Continuing the tradition she filled the clay jar daily, either at down or late afternoons from the tap, leaving the other times for the fairies. For her, even the tap water should be fairly shared with the fairies.

At first she was surprised no one asked for a cup of water in the city, which with time she got used to but she never stopped storing water because she was a firm believer that nothing on earth can last forever and one day a stranger or a kid would ask her for a cup of water.

The other grueling task she performed when growing was fetching wood for fire. Fetching wood was communal affair for the women who also made sure the village girls accompany them. And all collected pieces of solid and heavier dry woods for the women to carry and dry branches for the girls and when finished they walk home in line, one following the other, hunching their back under the load; their knees squeaking while climbing the hills but ignored the pain by singing, whispering and praying until they reached home. They did fetch wood collectively to distract their minds so their body won’t notice the burden in their back. But now in the city she did not have to do it because it was easily available with money. She was ambivalent at first because she missed the communal interaction and also missed the smell and look of the very woods she grew with and collected but with time she got used to buying it.

The men of the village never helped the women in fetching water and rarely for fire wood. For the highland man, fetching water and wood was strictly a woman’s job. He might pass by her while she struggled under the heavy load but he would say nothing like he would say nothing to a donkey laden with burden.

While enjoying the woman’s fruit of burden the highland man did not even try to come up with solutions that could ease her tasks. She would have loved it if he shared with her in her tasks but she did not blame him for not doing it as if all the tasks she did were the results of the sins of Eve that she was part of. She literally believed that as a descendant of Eve it was justified for her to pay the price for conspiring with the serpent to trick Adam.

To ease her isolation in the city she established economic associations with other women in her city community whereby every month all members contributed money and they took turn receiving the sum. They call it Ukub.

With other women who originated from her village and neighboring villages she also established religious association in a name of a saint whereby the members took turn to host party on the day of the saint. And they called it mahber. They prayed, they chatted, and they drank coffee and ate himabasha. She still had tremendous energy but fewer tasks in the city but by keeping herself active she maintained her tradition without loosing faith in her womanhood.

Through her undying will and efforts her neighborhood in the city took the shape and form of her village, where responsibilities of raising children became collective rather than household. She could leave her children behind in the neighborhood without worry even for weeks if she had to go due to urgent matters in her village. The women in the city neighborhoods took care of the children and the husband in her absence because the same thing could happen to everyone.

In the cities and towns there were women who came from all across Eritrea, all but the maid and factory workers, came married to city men or were already married before and joined their husbands in the cities.

The Hardy Kebessa Woman Meets The Lowland Woman

Whereas before the women were separated by mountain chains that bisected the land into highland plateau, eastern lowland and western lowland now thanks to roads, bridges and railway systems built by the Italians the women were able to meet and see one another for the first time in their life. Even though it was their first time to know and see one another closely, it did not take long time to build good relationship and understanding and in short time became comfortable with one another.

All the women looked alike mainly due to common ancestry and all displayed strong characters and conservative adherence to their faiths and values. The only superficial difference was the cross tattoo in the highlander’s woman forehead and piercing in the lowlander’s woman nose. Both women had beautiful hairs braided in slight different styles. The highlander woman braided her hair strictly from front to back while the lowlander woman braided her hair in all directions and also decorated her braided hair with colorful beads. Both braiding were stylistic and beautiful. The lowland woman was a bit more stylish in her clothes because she had easy access to varieties of fabrics from across the sea where trading was very active.

Every one liked the highland woman for she was stoic, honest and direct. Every one wanted to help and teach her too. To those things that did not violate her faith and values she quickly learned. She hated copying what she saw but was eager and curious to learn.

The highland woman never made efforts to learn the Italian language. Deep in her mind and heart she believed their presence was temporary and she did not entertain in temporary and passing things. She preferred long lasting things. But when she met the woman from the lowlands she was eager to learn her dialect and other values from her as she was prepared and willing to teach her own dialect and other values.

In short time, the highland woman who went to the lowland cities and towns learned the local dialect. What helped her was her uncluttered mind and clean heart. She was also free from all biases which made it easier for whoever was willing to teach her.

The lowland woman was bright, clean, dexterous, extremely beautiful with pretty white teeth (Tseba zimesil sna), humble, honest but shy nonetheless in short time she was also able to speak the highland dialect.

Once they formed the rapport they started teaching one another and learning from each other things they knew were safe for their core values and beliefs.

The highland woman introduced the lowland woman to coffee and the ceremony surrounding its preparation and the lowland woman loved it. In no time she was addicted to coffee. She grew up with bread and milk. When her virgin body tasted coffee it won’t let go. She did not mind, for drinking coffee also brought her closer with other women. But above all it was not Haram according to the Koran and it did not affect her values and faith. With time she experimented spicing the coffee for she was familiar with many spices that were unknown to the highland woman and the highland women would not wait to be invited for her coffee.

The lowland woman introduced the highland woman with Hina and Ilam, Henna for revitalizing her rough hands and chopped nails, Ilam for revitalizing her cracked feet; two herbs the highland woman never knew existed but badly needed. She venerated the Henna and Ilam just as she venerated the soap and the shoe introduced by the Italians.

The lowland woman also introduced the highland woman with perfumes and healthy sweet herbal beverage called Abaeke. Even though the highland woman found the beverage too sweet to her taste thus unpalatable, she prepared it anyway when she invited the lowland woman to Christian weddings. As for the perfume, no highland man can rest if he did not buy perfume for his good woman and it was the widely used compensation object for reconciliation especially if the man was at fault.

The Highlander Man Meets The Lowlander Man

While both the women, women who were separated by rugged and jagged landscape and who were born to two religions could easily form lasting and respectful relationship, the men were unable to replicate what the women did.

Both the lowland and highland city men were alike physically, mentally and emotionally. They were honest, hardworking, stoic but naïve and fragile. Both developed suspicions and fear they never had before probably the result of exploitation by the Italians. Both learned the Italian language for they believed the Italians will stay forever. Both started combing their hair mimicking the Italians and started using inordinate amount of pomades and hair oils. The worst was both started abusing and belittling their wives. Both frequented bars and other institutions and started neglecting their families.

Unlike the women, they introduced one another destructive habits and behaviors. The highland man introduced the lowland man to alcoholic drinks while the lowland man introduced the highland man to tobaccos. Their virgin body soon got hooked to those substances and some of their bizarre behaviors could have been the result of addiction to those foreign substances. Both men disrespected one another’s values and faith and slowly a chasm was created in their relationship. But the chasm was shallow and easy to rectify thanks to the women who forcefully filled the gap by preserving and practicing their values through good times and rough times. Had those men not been shamed and exposed of their behavior their relationships could have ended in violence and divisions.

Eritrea is a very small country with very small population. At any given time and place there is somebody who knows you. Those men who took the wrong values could not hide. The first to know were their wives, who gave chances for reform before telling the councilors or the elders called Shimagle; then the best man, and finally the monks and sheiks.

The monks and sheiks were not passive if they saw or detected transgression by any member of their religion. A monk or a sheik did not have to know you personally to chastise you. He did not even have to know what your religion was and like the women, the monks and the sheiks were honest, direct and daring. Because those who fell to the new bad habits were fragile it did not took long for many of them to reform. They were not strong to live isolated from their families, mosques, churches and villages.

To the erring highlander man, the attack came in all shapes and from all angles. The highland woman would threaten to leave him and to expose him to the shimagles (wahs mer-a), the best man (arki riisi), his mother and his entire village people, because smoking and getting drunk with alcohol violated her core values. So if the first threat did not move him she would expose him to the monks. The monks only knew yes or no to their demands and would not hesitate to excommunicate the culprit on the spot. To those who accepted their fault strict punishment was prescribed that included cleansing the sinned body with cold water (Mai Chelot)

The lowland woman was married to her cousin as dictated by her culture and sanctioned by her religion and tradition. Drinking alcohol violated her faith and her core values. Her threat was real and immediate. She only had to tell her uncle who would not hesitate to come armed with sword to confront his erring son.

Thanks to the hardy women who used hardy tactics many men were able to rehabilitate and regain their original self and were embraced back to the society.

The hardy woman never forgot what she learned. She made sure her sons and neighboring boys never repeat the mistakes done by some errant men. She tightened her grip vise-like and raised her kids with more discipline than she was exposed to when growing up in her village. As consequence, city and town neighborhoods resembled villages. Neighborhood relationships became carbon copy of village relationships to the extent that marrying your neighbor in a city or town was taken as incest. It was a victory to the hardy woman, a victory not bestowed but earned. Her fame shot high up the sky. She became the beacon and role model.

Stay At Home And Working Woman

The woman kept herself informed by exchanging news and rumors with women of her neighborhood because even in the city she continued the tradition of not drinking coffee alone.

Unlike in the villages, the city woman acquired habit of drinking coffee more than once a day and shared it with different women every time she prepared coffee. For her, coffee was not mere beverage. It was ceremony that involved many intricate stages and hours to execute. So to be invited for coffee ceremony was to be involved in discussion forums. Comparing to the men, the women were ahead in every facets of news that concerned not only their interest but also the interest of her nation.

The difference between the woman and the maid was the degree of personal freedoms. Both upheld the village tradition well. Both strengthened their faith and church well. Both were well informed. Both became more conservative in their attitude. Both remained direct, honest and faithful. Both dressed well but like their upbringing indulged less. Both adored the church and never left it alone. But the maid was free like the village woman more than the city woman. Where as the maid displayed courage, a trait she learnt while growing, the city woman displayed fear. The city woman felt oppressed and limited in her freedom and she started developing fear.

The maid strengthened her position by numbers because many girls started working in factories. Signor Baratolo, the textile factory owner, hired exclusively women for his factory and those women acquired the character and attitude of the maid. The made became their de facto role model and leader. Actually the factory workers were the first industrial workers in Africa. Baratolo hired them because of what he saw and admired in his maid and the female workers did not disappoint him. They learnt the process quick and were very productive and hard working. They worked in shifts, Monday to Saturday because they said no to working on Sunday. In no time, the factory became so profitable, the plant was expanded and more girls were hired. At one time the number of the maids and factory workers was equal to the number of home staying women.

Those working women and the stay at home women complemented and relied on each other for support and advice. Both were strong in faith and values, the same values that sustained their village and church. The mothers continued raising community children with their faith and values while the working woman continued solidifying her faith and values by rejecting temptations and worldly gratifications.

Those who teach learn and those who learn teach. The maid and the stay at home woman were reciprocating and complementing each other in areas of their strengths, expertise and domains of skills. The maid taught the woman new food ingredients and new cooking methods which the stay at home woman happily followed and started using cooking oil instead spiced butter. The stay at home woman braided the maid’s hair in traditional style in case the maid was visited by family or she wanted visit her family and village. The maid introduced new hair braiding styles she learnt from the Italians and though the stay at home woman would not use those styles on herself, she did it on her daughters and neighboring girls. The stay at home woman received the maid on weekends with both arm stretched and showered her with her favorite traditional food and coffee which the maid missed badly during the weekdays. The maid supplied news, local and foreign she heard in the Italian houses from radios and newspapers to the stay at home woman, and in no time the stay at home woman became enlightened in local and world affairs. The stay at home woman supplied the maid with village news and gossips in the highland and city neighborhoods and spared the maid from surprises and helped her feel rooted and attached. It took the stay at home woman time to use hair oil that was recommended by the maid because the stay at home woman thought if she use oil she would betray her mother who taught her to use butter which she called Likay and nothing else. But to the stay at home woman’s credit she used it on her daughters’ hairs long before using it on herself. The maid introduced pasta to the stay at home woman which at first strongly rejected but the maid being an inventive person mixed the pasta with the woman’s souse and the stay at home woman liked it and spread the idea first to her neighborhood and then to all the city neighborhoods. But before trying pasta she assured the monks of pasta’s nature and ingredients and they accepted her argument with condition: to not spread the idea to the villages and only to use macaroni. For every success there was also a failure. The maid, in a rush of excitement, also tried to introduce lasagna but the stay at home swore she would not touch it because she knew before hand the monks who rejected spaghetti would outright condemn lasagna. The teacher student teacher relationship reached its zenith when the maid begged to be the godmother of the stay at home woman’s daughter and the woman happily accepted the offer after consulting the monks on the issue. The monks’ positive answer was a confirmation to the maid’s unshakable faith and values. It was not easy for the maid to pass the strict test laid by the monks given her situation, situation filled with temptations and isolations. But she passed and surpassed the test and was allowed to become a godmother. The highlander Tewahdo believed the first person you meet after death is your godmother or godfather and that was why they put high premiums when choosing one or contemplating on an offer to those who wanted to become one. The stay at home woman reciprocated the goodwill by pointing to the maid of a good man to be considered for future husband which after hesitations and contemplations the maid happily accepted.

The maid and the factory worker were admired and envied for their belief and adherence to strict abstinence. The Italians first and then the British, the Ethiopians and for some time, American GIs were astonished at those women’s morality and strength of character.

The Highland Man And The Italian

The Italian rulers were not kind to the Eritrean men. They disrespected them and exploited them not that those men were any different than the maid when it came to honesty, directness, intelligence, effort or learning and doing things but I guess the Italians wrongly interpreted the men’s benign behavior and cooperation as sign of timidity and submission. How wrong they were.

The highland man was the product of the village women, women who collectively raised the man to be honest, respectful and kind to strangers and never to form opinion on others before facts. So the man did as he was taught to do. He showed kindness and cooperation towards the strangers, because he never knew strangers who harm. He learned the Italian language in short time, took direction from Italians and performed the task following their instructions and many times even made them better which facilitated the Italians’ plan to be completed in short time.

The highland laborer paid price with his life, his health, his safety and his loneliness to build roads, railways, houses and forts not an easy task in that rugged and jagged landscape. It was painful for the man to be away for long from his village and mother because he was his mother’s son and village product more than his father’s son. Had he been his father’s son he would have never became subservient to the Italians because the highland man abhors burden of any kind like every men elsewhere on the planet. There was strength in his weakness, strength of character hidden deep beneath patience, patience the size of his mother’s and village women but he was also fragile if separated from his mother and his village. Eventually he turned the patience he inherited from his mother and village women combined with the hard but structured and disciplined labor under the Italians into resilience. He became the most resilient man in the African continent.

It took Eritreans time to realize and identify the nature and tricks of their colonizers. But within the wasted time many developed harmful habits with disastrous results. Alcohol was the main culprit. Many started dying of new unheard diseases like kidney disease, ulcer and liver cirrhosis. Many also started bizarre behaviors of disrespecting women, elders, monks and even children. Many started calling their children “the sons of a woman”, a slight to tradition and power of the woman. Ironically it was the woman who raised him properly so he would not be called “the son of a woman”, a shame to the father for only good boys were their father’s son. Seeing those behaviors, drove the woman to be defensive but rather than fall into despair she became unusually aggressive, disciplinarian and overprotective towards her sons so they would not regenerate the new obscene behaviors and attitudes that threatened her core values and traditional power.

All city women joined by the maids, the factory working women and the monks fought hard to obliterate the new threat. They called the new threat cancer (Menshiro) and in many instances they won. To those who beat women, ironically they called them feminine (anstay), poo (har-i), cowards (jejawi) and added kab sebeiti ziharm gda ntilan zey harm, meaning “rather that beat a woman, why he didn’t hit an Italian?” Sometimes the neighborhood women spoke in audible whisper while he was walking by nrsu wedi sebeiti ndeku deki sebeiti yblom, meaning “he is himself the son of a woman, not his kids.” Other times the women say ms asebut zeibeas kab ms sebeitu, meaning rather than fighting with his wife why didn’t he fight against men.

The Hardy Kebessa Woman – Marital Relations

Those women who married good and respectable men warned their husbands not to socialize or associate with the bad men by saying trah imo mstom tsiukat yraika, gedifeka dekey hize adei k keid iye meaning “if I see you socialize with the bad men I will leave you and take my kids to my village”, a not easily said threat. If the hardy woman said something it was deemed done. The first line of defense for the woman came from the best man in her wedding. The best man would badger and cajole the husband to reform. The best man also used threat of breaking his friendship with the man, a serious threat not easily taken by any man of the highland. If the best man’s efforts failed then the task of pressuring the man went to the three counselors called “Shimagles”, three independent men chosen during the wedding in the woman’s home and tasked with responsibility of watch dogging over the life of the marriage between the bride and the groom. The villagers in unity also did their turn by threatening to punish the man with penalty both religious and monetary compensations while the monks invoked the threat of excommunications.

It was too much for many and many reformed. Some who reformed said ms izien men ywaga, meaning “who can win against women?” Some who half heartedly reformed said kab ms sebeiti mchkchak, mismaa yahish, meaning “it is better to listen than fight with a woman”.

At last the city woman was rewarded, a reward earned not just given. Her sons and daughters came even closer to her personally and under her tight but fair influence, an influence the result of progress, change and enlightenment due to her much improved and refined mode of handling. She also applied some of the mentoring she received from the maid and events she observed herself. To the dismay of the men, she started raising her kids just like “deki talian”, Italian kids. The men grumbled and said Sedidom yabiyu alewe, meaning the kids are growing without rules, a say that didn’t swayed or scared the woman at all because it was a white lie.

City Boys, City Girls And The Hardy Mother

The boys grew up confused but not the girls. The confusion with the boys was understandable. The father left everything to do with raising the children to the woman. He was always away from his family mainly due to work and the rest due to emotional detachment. He forgot that his sons needed to learn manhood from him, but to his credit, deep in his heart, the man trusted the woman was capable to fill the role in his absence because the woman who married was not different than the woman who raised him. He also assisted the woman if she asked for his help. He would say “listen to your mom, if you want to avoid my punishment” in a stern, serious, calculated and menacing voice.

Just like in the villages, the boys and girls in the cities and towns started growing up molded by their mother and women in the neighborhood. They knew they had a father. They saw him at home. They knew he loved and cared about them. They also knew he would ask their mom about them. They knew he would blindly support her arguments and concerns. They knew he would not hesitate to perform corporal punishment if their mother delivered a verdict of negative assessment on them. He was reactive and wanted to finish the task quick. Even though he grew up barely punished, he took punishing his children as his privilege and sign of power. He grew up as an individual and a member of the village but now he considered his children as his ownership. He saw them as burden and annoyance. If he brought them gifts, mostly clothing, he would first ask them to kiss his knees and they better oblige. To sooth his ego they kissed his knee before and after. If he forgot to buy them gifts they reminded him by saying “Dad I will kiss your knees if you buy me gift” to which he would reply “did your mother coach you to do that?”

The dread felt by the boys was not hypothetical. They had witnessed it in their own home and in the neighborhood. They had seen the actual punishment while delivered in real time to one of the boys they knew or did not know. But if the man was happy and ready to punish his erring boy, he would never lay his hands on his daughter no matter how his wife pleaded. Disciplining a girl was an exclusive task of the woman because he firmly believed that his daughter would neither forgive nor forget him if he disciplined her.

The hardy woman was always patient. She was never a reactive person partly due to her keenness and directness. She saw, she talked. Experience and hard upbringing also taught her not to be spontaneous. Hysteria was not part of her nature. To call that woman hysteric was tantamount to defiling her reputation. She gave early warning if she detected misbehaviors in her children. She would repeat and also escalate the warnings to threats of “I will tell your father if you continue misbehaving”. Those who heed her warning saved their thin skin and scrawny bones but those who ignored her warning were given away to the man who because of time and irritation would efficiently bring them in line. The woman was not happy every time she had to tell her husband to discipline her children because he did not come up with alternative reinforcement methods other than using force. Every time he lifted his hands she had to say “do not harm my child”, and if he ignored her she would snatch the child from him. If she let him beat the child and if the child cries, if not her, the neighboring women would interfere. Intervening was cardinal social obligation. If one encountered fighting parties, one could not be a neutral onlooker lest one be shamed for not trying to stop the fighting. Gender was not an issue for intervention. If the fighting parties were men, a woman can intervene. It was also a cardinal rule that those who fight stop if an outsider to their quarrel intervenes. Let alone injuring even ignoring the plight of a neutral person was considered taboo and sign of weakness.

Besides the women, the boys and girls in the city or town neighborhoods had other practical role models. As in the villages in which hierarchy was based on age, city boys and girls followed and respected the older boys and girls in their neighborhoods. The older boys and girls also took their responsibilities and duties in the neighborhoods seriously and diligently. Most of them came to the city or town already grownup. They were shaped in the villages so their reputation was not questioned. They were the first defense against undesirable habits and behaviors. They would not hesitate to discipline and if they did, no one would question their actions and intentions.

Afraid of the extreme consequence from the man; the constant badgering from the woman and the ever present eyes and ears of the grown ups, city boys and girls had no choice but to conform and behave. In most cases one could not differentiate their behavior and attitudes from their counter parts in the villages. They became direct, honest, shy and daring.

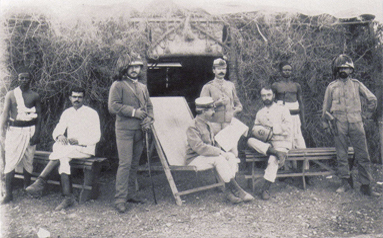

One of those boys, known by the name Zerai Deres, was taken by the Italians to Rome under the guise of education to join other captives from other Italian colonies for display during anniversary of Fascist party. He was typical Eritrean highlander who came to the city with his mother and siblings to join his father like many others.

In Rome, in that particular day, the Italian guards draped him in what they considered was African dress and also supplied him with spear and shield. When he realized what they were going to do he explained to them that in his homeland Eritrea people did not carry spear but sword. They consented and brought him sword. They took him and the other captives to a piazza where crowd had gathered and asked him to dance in African rhythms. Instead of dancing he came closer to the guards and to the horror of the crowd, who came to witness glory and greatness of Il Duce, beheaded seven of the guards. The remaining guards subdued him and remanded him to a prison where he was summarily hanged with no delay by the orders of Il Duce himself. Until now he is revered and remembered by all Eritreans as the first son of all women.

“The truth is that while men, in our society, are encouraged to have strong egos and to function in competitive, aggressive, intellectualized modes that may indeed cause them pain, for most women the ego is like a fragile African Violet, grown in secret from a seed, carefully nursed and fertilized and sheltered from too much sun.” Starhawk Quotes

Awate Forum