Gift of Incense: A Book Review

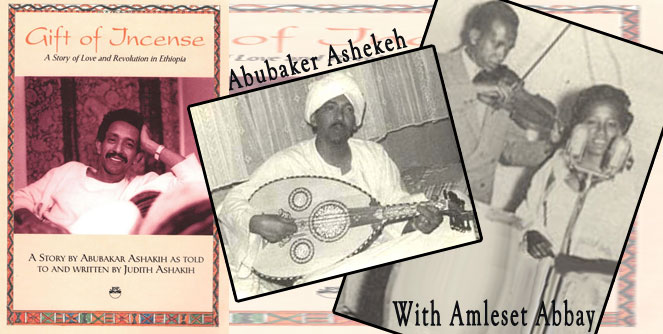

The Book: Gift of Incense ($ 24.95)

Author: Judith Ashekeh

Publisher: The Red Sea Press (2005)

Available at: Amazon and Countrybookstore

Review by: Saleh Gadi

Popular melodies are just remembered and hummed by many without the knowledge of the geniuses behind them. The songwriters and the musicians are barely known; the vocalist gets all the glory. Here’s a test of Amharic songs: when I say gara sr nou bettish, you would most likely say Alemayehu Eshete (or Teshome Mitiku [?]) How about Ye hiwetie hiwet? Telahun Gessese. Shegitu and many other “Ethiopianized” marching music? A few would know that the melodies are originally Sudanese1, by Ahmed AlMustafa, Mohammed AlAmin and others. But even fewer would know the subject of this review: “Sendelay”, Abubeker Ashekeh, the talented musician, who gets the credit for Ethiopianizing many famous Sudanese hits. That is why you need to read Gift of Incense.

I started to read the book one Friday evening and I stopped because I discovered the book needs a relaxed mood; many open-air hours on Saturday and Sunday brought me to its last page. Though I will review it for you here, you need to read this book yourself. It is excellent.

The objectives of this edition of Negarit are two. Actually three: 1) To prove once and for all that Keren is culturally superior to Asmera and Addis Ababa 2) Review the book, ‘Gift of Incense’, and 3) To silence ex-kerenites who were exported to the village of Asmera, from mocking Keren. Surely, the second objective is the most important.Reading ‘Gift of Incense’ is a pleasure to me because I can personally relate to the main subject and stories in the book. My father, a very close friend of Saleh Ashekeh, Abubeker’s elder brother, never answered my question about Abubeker when I was young; I think he was discouraging me from thinking of emulating him and end up a singer – who among us didn’t want to have a guitar and be a pop star when we were young? But years later, he confided to me that his peers, including Abubeker’s brother Saleh, were jealous of Abubeker because he was always well dressed, elegant, clean haircut and perfumed something that embarrassed the less elegant.

Those of us who come from the “bowl of Keren’s mountains” cannot help talking about Keren for any reason let alone when we get an opportunity to do so. This book offers a marvelous opportunity… to boast. That bowl surrounded by mountains gave birth to many people who contributed in many aspects to the lives of both Eritreans and Ethiopians. A glimpse of this captivating book rightly shows Keren to be a place out from a fairy tale that it is. It offers movie-like stories about the colorful town of Keren during and after the defeat of the Italian colonizers in WWII. Those were Abubeker’s childhood years.

Gift of Incense is written by Judith Ashekeh as told by her husband of thirty-two years, the late Abubeker Ashekeh. It is a story of “Sendelay”, Yimma Zeinab’s pet name for her son Abubeker. It’s the incense of the expensive Sandal wood that grows in limited areas in South and South-East Asia. Who is Abubeker Ashekeh?

Sendelay – Abubeker Ashekeh

Raised in the Ad Habab neighborhood of Keren, Abubeker thought “the world ended at the top of [the] mountains” that surrounded Keren, “never mind that [his] relatives came on camel caravans from beyond those mountains”. Abubeker “wed Mohammed, wed Hamid, wed Idris, wed Ashekeh, wed Mender, wed Oqba Micael, wed Araadom, wed Hinit, wed Be’ument, wed At’Keme [Asgede’s brother]” was born in Keren around 19342; lived in Asmara in his late teens; worked briefly as an oil pipe welder in Saudi Arabia in the early fifties; returned to Massawa and stayed there briefly; moved to Asmara for yet another brief stay; lived in Addis Ababa, “the oversized village” from 1961 to 1978; migrated to the USA in 1979; and died in 2000 in Lakewood, Ohio – “Sendelay” the exceptionally talented pioneer artist, died half a globe away from Ad Habab, Keren, his birthplace.

In the bowl-surrounded-by-mountains town, Abubeker must have been sneaking to wedding parties and numerous harvest season goylas, dances and feasts like Mariam Daarit and Ad Sidi and later fell in love with the Oud. Only Abubeker and Julio Mekhelef [Metcalfe]3 who grew up a few houses away across the yard of Bombet Ab Rayet, were the two people known to have been obsessed with the Oud in Keren. They must have been influenced by the young Sudanese soldiers who arrived with the British forces and policed Keren after 1941. At weddings and private parties, Abubeker watched very closely as the Oud players plucked the strings hoping to discover the secret of imitating the sounds. Thanks to his father’s wind-up gramophone, he was already introduced to Western music. Eventually, Abubeker owned his first second-hand Oud which he bought it from one of the soldiers leaving Keren. This must have been a fierce confrontation between him and his relatives and older brothers who “directed their disapproval at [Abubeker’s] willful determination to be a musician”.

Born to a traditional and conservative Muslim family, it is understandable how Abubeker must have been frustrated for not being able to pursue his musical hobby freely. But those who know him say that Abubeker was a rebel from his childhood. That frustration might have been the cause for his aggressive adulthood when he was considered “a one-man army” committing adolescent mischief that terrorized his teachers and challenged other adults older than himself who showed off in town. Keren must have been too small and suffocating for him. He wanted to go beyond the mountains and discover the world. And if you are born in Keren, the edges of the world started in Asmara. Keren was its center.

Abubeker left the center of the world to the edge of the world: Asmera, a city that was beginning to develop a few music and entertainment talents after the end of the Italian occupation. One sunny day, Abubeker must have arrived in Asmara equipped with an old Oud and his astounding skills of singing and playing Oud, mandolin, guitar and Violin. Important: a determination to make it big. In Asmera, he became an instant sensation. His most remembered song is a eulogy “Aba Hbesh Moytu Frqi leyti”. You know how it goes:

Quarenti, ny Leiti

Aba Hbesh Moytu Frqi Leyti

His first big opportunity came when an Italian company hired him to play Oud background music for a movie, called “Eva Nera” which was being shot in Asmara. The producers liked Abubeker and offered “to get [him] a passport and into a music school in Italy”. Abubeker traveled to Massawa to board a ship bound for Italy. But his elder brother, Osman, having discovered the plan, alerted a close friend the chief of the Eritrean police, the late Colonel (later general) Zeremariam Azazzi who had Abubeker “arrested overnight until [the] ship left” port.

I can imagine Abubeker instantly befriending the bottle from frustration. His opportunity for going to a music school demolished, Abubeker, started to play in night clubs and shows with similar aspirants of his age, names like the late Amleset Abbay, the vocalist who was “already famous”. She is mostly remembered for her immortal song: Sadulaye. Naabaye; Yehhshenni do msaKha mqnnaye!

But then there was mouth-watering news coming from Saudi Arabia.

In search of a better opportunity, accompanied by his friend Ibrahim Fekak, Abubeker left from “Imberemi beach” near Massawa to cross the Red Sea on a sambouk to Saudi Arabia. They “paid five British pounds to the boatman” for the trip. After a two-days sailing, they reached Jizan. And after another two days of resting, they “paid 12 Yemeni Rials” to a camel caravan to be taken to Jiddah. On foot! This is similar to the saga of today’s young Eritreans who are crossing the Sahara to reach Europe through Libya.

After eighteen months, Abubeker returned to Eritrea on board the ship “Josephina” to Massawa and met Abdul Karim Naib who “gave [him] a room in his house” and introduced him to the port city where he started to sing and entertain Massawans. Abubeker “music career really begun [in Massawa]” from where he returned to Asmera and played at “the Odeon Theater and Asmera Theater [where they] had live musical production once a month … playing violin and Oud and composing new melodies”.

Beginning 1958, Eritrea was chocking because of the encroaching Ethiopian control, rampant unemployment and political instability. The music business was being heavily censored and on May 15, 1960 [Abubeker] took the bus to Addis Ababa, the big village.

A Gift of Incense’ will certainly massage many Eritrean egos. The book has surprises and introduces the reader to yet another Eritrean, an individual who was instrumental to the success of the Kbr Zebegna Orchestra (KZO), Haile Sellasies’ Body Guard Orchestra: Lieutenant Girmai Hadgou. He was an officer who was shipped to Korea a day after his graduation from the officers school and served with the 1st. Battalion under General Aman Andom4. Lieutenant Girmai Hadgu, played the accordion, mandolin, piano and electric organ. He was a composer and musician for the Imperial music department. Liuetnant Girmay heard Abubeker play in a nightclub and later helped get a job with KZO “as a civilian”. He auditioned Abubeker in front of the “two generals, Girmamey, and his brother, Mengistou Neway5, as well as other officers.”

The organizational and promotional skills of Lieutenant Girmai were vital to the success of the orchestra- of course, the KZO was a propaganda tool for the king and no doubt it was generously funded and had its own radio station. But we need to realize that it is excellent singers like Telahun Gessese and Mahmoud Ahmed supported by the skills of Abubeker and Lieutenant Girmai who made the KZO what it was. And it was Girmai and Abubeker who spotted the talents of the shoeshine boy, now famous vocalist, Mahmoud Ahmed and brought him to the limelight to be hired by the KZO.

From his job with the KZO, Abubeker earned “$ 150 dollars a month” — a lot of money in the sixties. But it seems in the sixties, half the wealth of Ethiopia was concentrated in the hands of only a third of the residents of Addis Ababa while the rest of the 20 million or so people shared what was left of the national wealth. There was so much money to go around among the elite. Working as a musician, Abubeker must have resisted the urge to become a businessman for years.

During his time as a composer of the KZO, Abubeker composed hundreds of tunes that made many KZO singers very famous. The KZO popularized those songs. But Abubeker’s name, after staying on top of the Ethiopian music world during the sixties, vanished into the basements of Addis Ababa’s nightclub business. A great musical genius slowed his production of music. To this date, Abubeker’s mark on the Ethiopian music reigns defining the melodies of modern Ethiopian songs. A reader would not help but feel disappointed that Abubeker didn’t produce much music after the end of the sixties. I felt that when I came across the painter and architect Abdella Kekia’s6 name in the book, another famous Eritrean who contributed greatly to the Ethiopian urban lifestyle.

When I started to read A Gift of Incense, I expected to read other stories woven around the stories of Abubeker and his music; I was a little disappointed to find out that the focal point of the book was more of the Venus nightclub. The stories of Abubeker, including other relevant links were dwarfed by other less interesting anecdotes, real stories, emotions, grapevine leaks, gossip, and pet-talk to the extent that, at times, the main inspiration for the book, Abubeker Ashekeh, is dwarfed. But one needs to keep in mind that the sub-title on the cover explains that this is “A Story of Love and Revolution in Ethiopia”. Understandably, there is a lot of focus on the Venus club – which was more popular among those who do not know it than among its patrons. In my early teens, I heard a lot about it: A friend who came from Addis in the early seventies became a celebrity telling truth and fiction about the Venus club- “beautiful girls are ten-times the number of men”, he said. “American songs and electric guitars” he added. We just looked at him with envy. When I saw the old Venus location in 1991, though it was my first visit to Addis Ababa, I thought, it must have been fancy in its days. To me, it seemed a run down alley hole. But then, everything was run dawn after 15 years under the Dergue

Here are my three disappointments with the book:

1- I kept reading Amharic words that were passed out as Tigre words. I can’t imagine Abubeker’s Tigre-speaking father referring to a place that sells local brew as ‘Tej bet’, which is Amharic. He certainly referred to it as bet Khemarit. I can’t help laughing when I read Abubeker quoted as saying “my brothers called me Beshitegna“. That word being Amharic, his brothers must have called him “Hmum” in Tigre. There are also corrupted words like Imma and Ibba for Ymma and Ybba, Illeltas and a host of Amharic words stuffed as Tigre. Judith told me that she doesn’t speak Tigre and that Abubeker talked to her in either English or Amharic. That explains her language mix up. The publisher should have passed the book by a Tigre-speaking editor before print. I hope this is corrected in the second edition – I have a feeling there will be one.

2– I felt uneasy reading personal stories of people lavishly and liberally discussed in the book. For example, names of prostitutes and children; and gentlemen dropping their pants because they were too drunk to notice – I don’t know how those ‘close friends’ would feel if they read such private issues exposed. Again, maybe it is my socially conservative views but I thought such things have a doctor-patient type of confidentiality.

3- The book is not indexed; when I started to type this review and I wanted to reread some parts. I had to tediously flip page after page to find a single line.

At any rate, Judith Ashekeh offers us an excellent combination of her autobiography and a biography of her husband for 32 years, so vividly detailed that a reader of the book would feel he has been sharing a room with the Ashekehs for decades. Gift of Incense is definitely an interesting reading for those who grew up in Addis Ababa because it will take them back in time to the seemingly ancient sixties and the volatile era of the seventies. It is also a great reading for young Ethiopians to learn how Addis residents coped with life in those years. It is a great reading for Eritreans who will discover the contribution of Eritreans to the Ethiopian music culture. They will compare life between the Dergu’s Ethiopia and the PFDJ’s Eritrea. Furthermore, readers will learn about Abubeker’s musical genius albeit the fact that he abandoned music prematurely. As for me, the book filled some empty patches about my knowledge of Keren of the forties and fifties, the young days of my father’s generation.

1– Example of Ethiopianized songs:

Original : Wen ya nas Habib arrouH- wen ya nas ana gelbi mejrouH – Mohammed AlaMin

Ethiopianized: Woy nana yagerye ljji- woy nana yagerye (?) ljji – Telahoun Gessese

2– I am guessing the date from the stories and the ages of Abubeker’s peers.

3– Julio Mekhelef [probably a corruption of the Maltese or Cypriot name Metcalfe] is a peer of Abubeker who never left Keren and played the Oud at private parties and weddings.

4-Aman Andom, a general of Eritrean ancestry who was the first leader of the Derg that deposed the emperor in 1974. Later killed in a shootout by Dergu itself over policy differences concerning Eritrea.

5-The two brothers where killed by Haile Sellasie after their failed coup attempt while the emperor was in a state visit to Brazil.

6-Kekia is a talented painter and Architect whose work adorned the colorful old Ethiopian postage stamps. Kekia’s fingerprints are all over Addis Ababa, starting from the tukul inspired Bolle Motel to many others. Before I forget, he is from Keren. Now you understand why I claimed that Keren revolutionized the Ethiopian culture!

Comments: articles@awate.com

Awate Forum