Defining The Eritrean Catalyst For Democratic Change

In my previous article ‘Eritrea: The Missing Element for A Democratic Change”, I concluded that the forces of change in the Diaspora are the most compatible element for catalysing prompt change in Eritrea and ensuring desirable outcomes. In fact, the catalyst role is the only viable option for the forces of change in the Diaspora. For the Diaspora to execute this role perfectly, consciousness and conviction in the nature of this role, and the embedding of the role in a detailed action plan are essential. The quality of the execution of this action plan will be proportional to the speed with which change is brought about and the achievement of a stable and democratic state.

The first part of the article identifies three primary issues as major obstacles that hinder the forces of change inside Eritrea: First, the lack of information and its negative psychological impact (which can be addressed with a well-designed media message); second, the support that the regime seems to enjoy from Eritreans in the Diaspora, particularly the recent youth migrants, the well-orchestrated YPFDJ activities and the effects of their coverage through the regime’s media outlets (which should be countered with parallel activities led by the forces of change in the Diaspora, taking advantage of Western countries’ sacred values of democracy and human rights, and their correspondence with the demands of the forces of change); third, the uncertainty regarding the replacement of the current regime in light of many failed attempts at change in the region (this can be overcome by developing a consensus among the forces of change regarding the transition period and beyond–the consensus should include an action plan for the change process which should be characterized by integration, not competition).

This part of the article focuses on assessing the forces for change in the Diaspora, taking into account their ability to tackle these three major issues that hinder them from catalysing prompt and safe change in Eritrea.

The requirements for the catalysing element

Characterizing the forces of change in the Diaspora as the best suited element for catalysing change in Eritrea does not imply that its presence in itself is sufficient to fulfil this role. In fact, the willingness of the Diaspora to execute this role is also necessary. Its attempts to engage in any other role may be legitimate but ultimately not viable. Achieving change from a distance is a seemingly unfeasible task and has not support regionally or internationally. On the other hand, achieving change through conventional military operations is out of the question for objective reasons that do not need to be detailed here. Change through negotiation is not an alternative either as it is not commensurate with the regime’s nature; it does not recognize the existence of any internal problem that require negotiation or compromise. In fact, it attributes Eritrea’s dilemma to exogenous factors.

Ruling out these scenarios leads to the only feasible option: integrating the efforts of the forces of change inside and outside Eritrea. This involves assigning roles among them based on their respective natures, capabilities, and locations. Although this notion sounds simple, plausible, and clear, the fact is that most of the forces of change in the Diaspora do not know how to bring it about. The past two decades have proved that these forces oppose the regime in principle but are unable to transform this principle into a doable and effective action plan. Consequently, opposing the regime has turned into a sort of a routine act that features no creativity, surprises, or breakthrough regarding any of the elements that are necessary to bring about change in Eritrea.

The relationship between the forces of change inside and outside Eritrea

Due to historical circumstances related to the formation of the Eritrean opposition, it is virtually non-existent inside Eritrea. As a result, its evaluations of events in Eritrea are likely to be inaccurate. While there are justifications for this non-presence, the absence of opposition discourse is inexplicable in light of the remarkable advancements in communication technology. It is no secret that for more than two decades, these forces have failed to establish effective media to carry their messages to the people inside Eritrea and to expose the regime’s notorious practices and propaganda. By contrast, the regime’s media, particularly its television, seems to be effective in attracting a growing audience. It is the only space that fulfils Eritrean longing and nostalgia. In light of this deficiency, establishing media that is technically effective and transmits a message that is sound in essence is a priority. For the message to be effective, it must focus on our people’s strength, with special attention to the forces for potential change, particularly those in the medium and low ranks in the army, the civil administration, traders, students, youth, women, and farmers. The essence of the message should be the ushering in of fundamental solutions to the nation’s dilemma based on collective efforts. It should also highlight the sentiment that the country in its present state is not a solution to the problems of individuals or of the people collectively. Shedding light on the people’s heroic record during the armed struggle, when they never surrendered or compromised, is pivotal. Addressing well-managed diversity as a source of richness is also essential. Messages that focus on coexistence, peace, and political and social consensus will certainly push away worries about uncertainty. The future that this message ushers in should be a democratic state grounded on the principles of citizenship, equity, and equality. Discourse should be subject to zero tolerance for domination or marginalization, in theory and in practice. Moreover, the regime’s tactics to divide the nation should be fully exposed and confronted; its human rights violations and its humiliation and degradation of the people should be documented, not tolerated. The message should send clear signals to the forces inside Eritrea, which have a great interest in bringing about change and the capacity to do the same, that no messiah will come from outside Eritrea to change the regime. The main burden lies on their shoulders, and the forces for change in the Diaspora will provide as much assistance as possible. For this message to be heard, effective tools are necessary, adequate human resources should be recruited, and methods of assessment should be adopted.

These are the prerequisites for catalysing change in Eritrea. Assessing the existing efforts of the forces for change illustrates that, although various individuals and organisations have initiated efforts, they are far from reaching the level necessary to awaken the forces for change inside Eritrea. Logistics and deficiencies in funding have always been proposed as the cause of this shortfall. However, the fact is that lack of vision is mainly responsible for the failure to establish effective media. This leads to the conclusion that the forces of change are not yet ready for the role they have to play in the process of change.

Mass Mobilization

The recruitment of masses in its affirmative form will empower the people who consider themselves part of the forces of change, regardless of their affiliation or non-affiliation with political or civil organizations. In its preventative form, it will win over the regime’s supporters or, at least, neutralise them. It is crucial to work simultaneously in both forms in order to catalyse change in Eritrea. Empowering those who are affiliated with the forces of change contributes to supporting the organized efforts, creating leaders, and motivating the forces of change inside Eritrea. Moreover, the preventative form of the same weakens the regime economically and politically. At the forefront of the preventative form are efforts such as targeting the youth who recently migrated to Western countries. To this end, setting up a flexible strategy is a core point. The strategy should be based on a simple concept, namely, that this category, including YPDFJ, can be won over to help bring about change in Eritrea. This concept stems from the fact that these people fled their home country, leaving their loved ones, memories, and comfort zones behind them. They would not have made that decision unless they were fed up and had lost hope in the current system of governance. This leads to the plausible conclusion that these people are not in favour of the continuation of this regime. The perplexing phenomena of these youth supporting the regime once they settle in their new countries owes more to the weakness of the forces of change in the Diaspora than to the strength of the regime and its satellites. The regime has taken advantage of this situation and opted for a very effective strategy based on the half-open-door policy, which requires the youth to sign an apology for leaving the country illegally but simultaneously reassures them that they will face no legal consequences. As was explained earlier in this article, signing the apology letter gives the signatories access to consular services and allows them to nurture the dream of returning home for vacations or for good, whether or not such a dream is feasible. Furthermore, the signatories protect this dream by supporting the regime. Alternatively, they refrain from opposing the regime by avoiding actively joining the forces of change in the Diaspora. To promote its strategy, the regime consciously dissolves the frontiers between itself and the nation by using the terms “nation” and “regime” interchangeably. It also plays the sectarian and regional cards. If doing so does not yield the required outcomes, then it may threaten the targeted people with reprisals against their families or relatives inside Eritrea. Fortunately, the regime’s tactics for recruiting or neutralizing Eritreans in the Diaspora can be defeated, particularly as this segment of the population faces a moral dilemma by enjoying the benefits of democracy in their countries of residence while supporting dictatorship in their home country.

The impact of this phenomenon on the process of bringing about change in Eritrea is crucial. On the one hand, the regime-controlled media’s coverage of this segment’s activities sends the wrong signals to the potential forces of change inside Eritrea, leading them to believe that they have been left to their fate and that those in the Diaspora have no sympathy for their plight. Such contemplations eventually lead individual solutions to outweigh the collective one. Moreover, these activities vindicate the EU’s and its states’ assessment of the motivations behind the exodus, leading them to label the youth economic migrants. As a result, the Eritrean cause is deprived of its political dimensions, and the EU’s assistance to the Eritrean regime receives justification. This is the last thing that those who seek justice want.

The issue of youth in the Diaspora is the cornerstone of any efforts to bring about change in Eritrea. The regime’s strategy, which has multiple dimensions, seems to favour the continuation of the current situation as the only viable option. This segment’s sympathy or indifference towards the regime is counterproductive for any attempts at change as any project to bring about change in Eritrea must stem from a sense of urgency and must be fuelled by an individual and collective sense of injustice. Needless to say, the regime’s strategy aims to defuse this energetic feeling.

Setting up a strategy to win back this segment that favours change requires, first and foremost, refraining from labelling it selfish, brainwashed, or as Nazi, as some extremists do, particularly in the social media. The suggestion that this segment should automatically be a principal part of the camp of the forces of change due to its knowledge regarding the dictatorship of the regime is absurd. A doable strategy should be based on understanding the psychological, social, and financial pressures that this segment endures during and after its journey and on strategy characterized by empathy but, most importantly, underpinned by a workable action plan for change that has feasible post-change alternatives. As such a strategy seems beyond the reach of the forces for change in the Diaspora, it is clear that they are not even close to being able to play the role of a catalyst.

Concerns beyond change

The third aspect of fulfilling the catalyst role involves providing clear answers to the questions that arise as a result of change. Fears and hopes regarding what the future holds are instincts embedded in each individual’s consciousness and, consequently, in the nation’s collective consciousness. When it comes to bringing about political change in Eritrea, fear outweighs hope as there are many dreadful precedents of attempts at change failing in the region (for instance, in the cases of Yemen, Syria, and Libya). The Eritrean opposition, particularly the Eritrean Alliance and Eritrean Council for Democratic Change has endeavoured to address the issue of the transition period in its conferences and charters. However, overcoming such legitimate fears requires more than a chapter in a political charter, particularly if the charter’s signatories disagree on the same issues at a later stage, beginning the journey of internal fragmentation and defamation. Any serious attempt to tackle this aspect should first address a broad, binding consensus based on fundamental issues such as the unity and integrity of Eritrea and its people, language, land, a peaceful power transition through a democratic system based on citizenship, affirmative action based on scientific studies, and adherence to international laws. This consensus should be above the political organizations’ manoeuvring and elites’ passiveness.

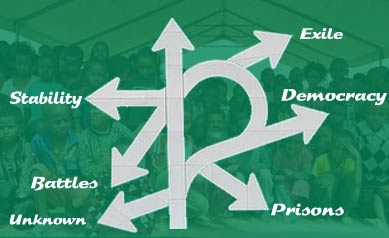

Second, there should be an agreement on an action plan to bring about change in Eritrea that is characterized by integration, not competition. This includes the aspects of resistance and mobilization, mechanisms for the transition period during which the roles of the potential forces of change inside Eritrea will be clearly assigned. Evaluating the forces of change in the Diaspora in this respect illustrates how far it is from assuming that role. To make the situation worse, the forces of change in the Diaspora has opted to address these issues by forming political umbrella groups. However, dysfunctionality, inefficiency, and fragility always characterises these platforms. That cannot be effectiveness in bringing about change and contribute positively to a smooth transitional period, if change occurs. The insignificant accomplishments (such as the National Council for Democratic Change) due to political manoeuvring is not only disappointing but is also a clear sign of the immaturity of the Eritrean opposition which is presumably the alternative to the incumbent regime. Hence, the current situation is not just delaying the long-awaited change in Eritrea, but it is also diminishing hopes for a stable and democratic country even after the demise of the regime. This means that the possibility of Eritrea slipping into the pattern of failed states cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

Development a process for bringing about change that is a stable, democratic replacement in Eritrea promptly requires the accumulation of many factors. Eritrean inside the country are as capable as any other people of revolting against injustice if a conducive environment is created. In fact, Eritreans are known for their resilience and determination, values that were tested during the armed struggle and eventually achieved independence. Alas, the euphoria of independence numbed these qualities in the people. Ironically, the pain that the regime has caused has led to the reviving of these values and to the formation of forces of change inside Eritrea. To fully awaken these forces and ultimately bring about change, however, the forces of change in the Diaspora, which enjoys the luxury of free speech, freedom of association and advocacy, must play their catalyst role effectively; unfortunately, these forces are far from ready to assume the role. Thus, bringing about a smooth change and transition that ultimately leads to a peaceful and democratic Eritrea is currently a mere mirage.

Awate Forum