Akria: Memories of Childhood in the Garden Among the Flames!

INTRODUCTION: What you are going to read here is not history! But it is not fiction either! You may consider it a trail of memories that an Akrian boy may have run in his mind during the last crisis in the neighborhood. For sure this essay is not history but history can be made from it.

Some Names in this essay are altered to protect privacies.

The Neighborhood

Akria is located to the north-east of the city of Asmara. During the period considered here in this essay, this neighborhood seemed as if it were a city within a city. The interesting peculiarity about Akria was its social and cultural replication of the capital of which it is a part. But replication in population-combination, culture, and temper was an intrinsic characteristic of the city. The Capital as a whole was also, as just hinted, a replication of the whole of Eritrea in all its multitudes of culture, religion, and ethnicity. The story doesn’t end here, for Eritrea as a whole is a replication of the entire region and all its elements; is it not true that you will not find in Eritrea a nationality/tribe or an ethnic group that does not have a larger stretch beyond Eritrea’s political borders? This indeed was, at the core of the image of the mother city as it was for the whole of Eritrea: diversity all pointing to external extensions.

Akria was then the Home of a Muslim, a Christian, a native and a foreigner. Jeberti Muslims were the majority of the inhabitants of Akria, but there was a sizeable Christian presence in the northeast and west ends of the neighborhood. There were others too in Akria: Yemenis, Somalis, and Italians living beside the citizen, as there were sections of Akria pointing to other Eritrean and non-Eritrean elements such as Riga Shaho (warda filo), for the Saho and Riga Somal for the Somalis.

Akria had numerous mosques in its different sections and there was also that great church of Gebri’el in its northeast corner, while a grand Mosque stood on the southern edge of the neighborhood, just at the northern bank of the Wadi known as the ” Wahji Madishto” at a section, “MayBottlioni” at another and “MayBela” at a third section.

What is in a name?

The name Akria and its origin is a riddle in itself, a host of a number of unrealistic and simplistic solutions! There was only one between the solutions to this riddle, which should, in my opinion be merited with the rating “probable”. It was related to me in two occasions by two knowledgeable personalities, first by the late Ustaz Nurhussein Aberra, an Eritrean lawyer and philologist, and again, lately, by an elderly intelligent, knowledgeable man living now in America, himself being one of the early dwellers of Akria as a child at its beginnings in the late thirties or early forties of the twentieth century. The two gentlemen, without knowing each other, corroborated each other’s story saying that the name Akria is an Italian corruption of another indigenous name: “Shakha Akia ”!, a description of a wet small part on which a wild thorny plant, Akia, grew, now taken a name for the whole empty area, later corrupted to Akria by the Italian municipal bureaucrats.

The Map

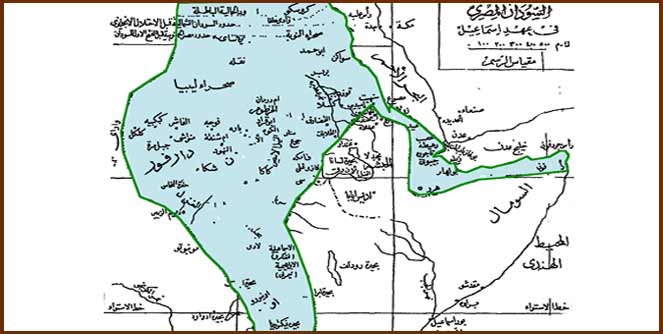

In the beginning, Akria was not within the city itself but appeared first as a separate village, relatively away from it. This view is reinforced with what you would have seen if you had visited the Asmara municipality building in the 1970s and until the beginning of the nineties, and that old map which adorned the wall on a corridor to the lobby leading to a waiting room, drew your attention and lured you to scrutinize and have a closer look at. Had you done so, you would have seen the north-eastern tip of Asmara empty, and a short distance away from it, an empty white area, fine lines dividing it into square and rectangular shapes, and a writ along the same area with relatively large Latin characters reading: Villagio Acria.

The Wadi

From east to west, a wide ditch or, rather, a narrow Wadi run on the extreme south of Akria starting up at the northeastern hills overlooking Akria at “aguadu, a newer name for the Villagio Maria Scalera ” and down to its long westerly course. The Wadi had a different name at its different courses. At one point where it runs crossing the “Idaga Arbi” road (which is also the extension of the main road of Akria) , under a covered culvert ( known to the public as Bunto) and entering thereafter to cross the road from Akria to “Haddish addi” taking the name of “Wahji Madshto” where it henceforth carries this name until it reaches the foot of “Geza Banda” and “Abba Shawil” where it changes its name to “May Bottolione” and keeps it until it crosses the Road to “Idaga Hamus” where it changes its name, once more, to “May Bela” and continues so to a long distance passing, this time, as an all covered culvert.

It is thus clear that this Wadi separated the neighborhood of Akria at its southern side from the northern part of the city. Taking Haddish Addi (another neighborhood of Asmara neighboring Akria) as an example, it was separated from Akria by an empty and cultivated area of land extending for more than 300m. The same can safely be said when speaking of the other next-door city neighborhoods “Idaga Arbi“, “Geza Banda”, and “Idaga Hamus”.

The Mountain

At the northern end of Akria stood a huge red-tinted mountain known to the inhabitants as “Gobo Siraj Omar”, nevertheless, the mountain associated with the name of Sheikh Siraj Omar, a wealthy businessman, is a little baffling, since no one may tell you, for certain, if the name of the man bound to the mountain was an expression relating physical ownership or one of symbolic packaging. But this is not the only wonder that this mountain displayed! It is, to start with, a mountain that took the slippery road to vanishing and dying under the full watch of all those around it. For years, pieces were falling down every now and then to, quickly, be further cut into smaller parts, rounded, polished and sold for construction and building houses. Time came when they didn’t have to wait until pieces fall on their own free will; they discovered a way for causing the same effect by employing bigger hammers and chisels. It was all organized and someone must have been making all the money, someone you wouldn’t have seen between the men using the hammers and chisels. But for the sake of truth one would say that they were methodical and merciless (like all money grabbers) at mutilating the mountain, until one day they struck the mountain at heart and created an ever growing hole in its face, a hole behind which you could see the void which sprung out into being behind what was the cover, long offered, by the mountain’s face. Many of the city’s houses were built from the polished boulders and stones of the Quarry of “Gobo Siraj Omar”. But now, the mountain is left alone in its old age, showing a miserable countenance that tells very little of its past. Yet, in the end it is the dying mountain which had the last laugh! Many of the houses in Akria and in the city at large were built from the bits of the body of the mountain. The boulders and stones, being indigenous elements, have helped these houses, so far, in showing no sign of failure although fatigue here and there is inevitable. The houses built from the quarry’s boulders has survived and outlasted those built with bricks and mortars in much later days.

The Brick Factory

There were lying at one time at the northern bank of the Wadi, where the grand mosque at Madishto now stands, the ruins and remnants of a brick factory with its Brick-baking oven and its red high chimney kicking the sky with a call of challenge inviting the little boys of the neighborhood to brave themselves and go up the dark chimney climbing its rusted steel rungs to have a look down to the world beneath from such a summit as the chimney’s top. No one seems to remember when this plant was last active and operational, and it seems that it did not contribute to the building of the neighborhood as most of the buildings there were of stones and boulders from the famous mountain. The ruins of the bricks making plant were finally removed to allow space for constructing the Madshto grand mosque.

The Lake

There were a few small lakes in the northwestern of Akria the biggest of them all was the “Mai’nbessa” lake. This was the main source of water for Akria carried and distributed to houses on donkeys as the city municipality didn’t care further than levying real estate and other taxes. Mai’nbessa was a real lake which no one child dare swimming in, the water level measuring staff in the middle of the lake though showed fluctuating levels throughout the year never went below the middle marker. The smaller muddy lake or rather pond, not very far from “Mai’nbessa” was known to the boys as “Bogabbuf”. They used it as a swimming exercises pool, disregarding their parents’ advice and orders not to go near that lake scaring them away by the jinni that would pull them down to the bottom as it did to many boys. Some five hundred meters from “Bogabbuf” was the small stream falling from a higher grounds to the shrine of “Sheikh Abdussalam and Alimuz for the Muslims” and “Inda Mik’eal” for the Christians. It was a complex of common shrine for the believers of both communities. People with ill-health would come there and immerse themselves into the falling water. Later on the spring feeding the stream went dry but the shrine was still visited by many people especially on Tuesdays, the day of Sheikh Abdussalam.

The School

There were no schools in Akria prior to 1952, but in that year the community of Akria with no contribution of the state, founded the Akria elementary school and its management was assigned from within the community. The school used to teach children at the elementary level and after the necessary four year course the students were to passes to a middle school “ The Islamic benevolent middle School” in Idaga Hamus another school also founded by the community, without any help from the State. Both schools where, in a step by step manner swallowed by the successive governments. The trick was always the same and consistent in that the government offers teachers, whom she pays, and then a new curriculum is imposed and the school is eventually the government’s property from that point onward. Then a third school was established by the community in the early sixties, without any help of the state this time too; it was established as a fruition of late Ustaz Basher’s efforts and initiative. He further transformed his initiative into a community project which showed its successful approach to education by and through community. This was the “dia” school of Akria, and at this point I don’t need to go on its story, you all know it.

The Street

All the streets of Akria were straight: parallel and intersecting and you would find no anomaly to this rule. There was nothing to distinguish between these roads and streets, and you would feel the more bewildered if you were told that the people there were describing and naming them by their widths. Acria Streets were of three classes the VIA 16, VIA 8, and via 4. There were many of class 4(Via Quarto) and less of class 8 and only 2 of class 16 in Akria.

Via Seidici

One of the two class 16m streets was the main street enjoying the regular Bus Service starting at a point in the northern sector of the street to Idaga Arbi, to the center of the city and finally to Godaif. That stretch of Akria where the bus service runs on was the liveliest and most interesting road in Akria. It has 2 tea-shops, 1 owned and managed by Reshad the Eritrean, the other owned by Sharbah, a Yemeni. There were three grocery stores, butchery, a Gold-Smith, a shoe repair, a police station and two charcoal selling yards, a smaller one owned by the Yemeni Mani’e and the other by the Libyan Mustafa. There was also one huge farm in the middle and in between the houses at la’elay Akria owned and managed by aboy Bairu, a funny nice old man when he is not drunk. He was making a good business out of selling his products of different vegetables especially the lettuce for making salads but his specialty known throughout much of the city was his Rue plant (ጨናአዳም) much needed for use in local medicine, relieving cold and other minor health problems. His competitor was a much wealthier Italian, Vaccaro, who had his farm, which includes a complete husbandry, in the west end of Akria. He used to sell milk which comes with a carrot as a bribe to lure the kids coming again for his merchandise. He also used to cater for far away stores and restaurants in the city. Gido Then, there was “Gido” and his workshop-on-wheels! He was an Italian, who, god knows how, arrived into Akria and took it for a home! And indeed he was part of it, all the same. Driving out his workshop-on-the-wheels Gido would wander and spend a good deal of the day in the Streets of Akria earning his living by sharpening household knives, welding old utensils and fixing whatever accepts fixing.

Gido was an Italian who lived in Akria since the end of the Italian era in the forties of the last century through the British Administration phase into the Imperial Ethiopian occupation and the Derg era. He was one of four other Italians who took Akria for their home and residence. Gido was a stout man of below- average- height, bald-headed and, perhaps, that is why you would never see him without his shabby black hat over his great bald head. He used to wear pants larger than his size fixing it around his waist with a rope very much similar to those extended and used to hang clothes for drying. It was difficult to guess and describe the color of the shirt underneath the worn-out black coat he was wearing, since Time, augmented by metal sharpening dust and smokes from his utensils-welding, has done a good job paling and changing it multiple times. All this was sealed by his huge, also worn-out, shoe the type of shoes used by police and Army personnel, giving Gido the exact outlook of “Charlie Chaplin” in his early pantomimic movies. It is true that Gido showed little obesity, a description absent in Charlie’s detail, but he, nevertheless, looked like Charlie in every other bit of definition. Gido was living an isolated life, alone with no wife or friend, in a house that he owned or rented and where he admitted no visitor at all. Had you have the opportunity to see what the young devils where peeping at through the key-hole of his door, you would see that the man was living in a colony of rusted steel and iron of all types scattered and lying everywhere: rusted chains, wheels, hammers, car parts, keys, nails, rusted nuts and bolts and whatever your imagination would give. Gido was known by the boys as “Gido Ladro di gallina”, and, I assume, you don’t need much imagination to know why he was called a chicken thief!

Gido had a side job besides honing kitchen-knives and repairing utensils, he could read palms and tell fortunes, but the urchins of Akria thought that he was excelled and surpassed in this field by the Maltese who was passing as an Italian and whom the children called “Ammna Mokhos” perhaps an indication to his extreme height and his extremely skinny body. It seemed that He was the most learned between the white men living in Akria. He, always, walked swinging his cane in a hand and holding books and newspapers in the other. People said that he was working as a magician in an Italian local newspaper reading fortunes of readers. As such he was seen with a mixture of respect and apprehension.

The belle rebel

The main road of Akria on which the Haragot bus was regularly running had characters more interesting than Gido and his group of Italians. One such character is Zeineb, a character worthy of respect, admiration and love. She was the most beautiful, most charming and most courageous girl in the neighborhood. She had a striking beauty, impressive on anyone who set eyes on her tall stature, smooth dark complexion, white shining teeth, and ever-smiling-wide eyes. She was the dream of every young man but no one dared approach her impregnable personality. She was an orphan, living with her mother, a humble smalltime business-woman who used to re-sell fabrics bought from downtown Arab and Indian owned shops, krkab sandals (ቅርቃብ), fake jewelry, and accessories. She was helping her mother in her business by going to houses displaying her mother’s merchandise in the mornings and selling small quantity vegetables at her mother’s house doorsteps in the early evening.

Zeineb’s beauty and character attracted the attention of a wealthy Yemeni who dared thinking of her as his bride. His wealth and extravagance lured the mother to welcome and agree to his proposal, But Zeineb had a different opinion on the matter as well as the audacity to face her mother and, firmly, reject the man and his proposal. All possible ruses, threats, and pressures applied by the mother and her relatives to subjugate the mutinous belle failed and were all gone with the wind. Nevertheless, the mother decided to go ahead with the marriage plans and ram it down her daughter’s throat. Consequently, the preparations for the big day were in full swing until the eve of the wedding day when Zeineb mysteriously left her mother’s house and disappeared without leaving a trace. For three days her mother and relatives looked for her everywhere they thought she could get hiding or refuge, but all was to no avail. However, in the morning of the fourth day she appeared at her mother’s doorstep with most of her face and her forehead rolled and covered with a Netzla (ነጻላ) which when she removed, the mother had to drop down fainting. It appeared that the girl has shaved her head zero including her eyebrows. Later that day it was rumored that the girl threatened that if she were forced into this marriage she would repeatedly and always shave her head and add to that shaving her cheeks and chin until it grows full beard. When the news reached the wealthy old groom he understood the message, and with shame and sour feeling, he had to drop his plans for owning the pretty girl. There was, however, one of those who was present in the mother’s house that day, and saw when she arrived and uncover her head, he had, later, one comment to say: “that old groom should have held out his position and accept the girl’s condition for accepting his offer and take him a husband, why not? She was looking even prettier after the shave.

Zeineb married another man of her choosing a little less than a year after the incident and I know that she lived until few years ago.

A Rebellious neighborhood

Zeineb’s Spirit of rebellion seems to have been a reflection of the bigger rebellious spirit of Akria. Since the day it was founded in 1939-1940 Akria manifested, unambiguously, it’s burning spirit of insurgency and rebellion. An Eritrean intellectual and veteran Tegadalay, Wolde Yesus Ammar, in his most touching article in memory of “Seyoum Oqbamikael (Harestay)” which he wrote on the day marking the 12th year of the untimely death of Harestay, has this to say about Akria:

“As every genuine patriot worth his/her salt would confirm it – and forgetting the bla bla of revisionists of history and facts – Akriya was always a hotbed of nationalist politics inside Asmara, and a hiding place for freedom fighters. Even Martyr Seyoum Harestai spent a couple of nights in an ELF urban hideout rented inside Akriya in August 1965 upon his (and Woldedawit Temesghen’s) return to the city to organize people. (This writer, who attended the Mai Anbessa meeting of 55 years ago, also had the honor of spending a night with the two ELF fighters in Akriya precisely 52 years ago). Hajji Mussa M. Nur, co-organizer with Martyr Tuku Yihdego and group of the ELM/Mahber-Shewaate demonstration over a year earlier, and who provided shelter and logistics to heroic Saeed Hussein and his ELF Fedayeen team for the successful airport operation of 1963, was for sure in Asmara/Akriya in May 1962 and was no doubt proud of what the young students were doing. One would hope he will survive the PFDJ prison of today and tell us how he would compare the 31 October 2017 demonstration with the demonstration of May 1962!”

The Fall of the cactus tree

There are yet further manifestations to the rebellious mode of Akria throughout the years of oppression into the present days of slavery. Take this history of Akria of the sixties which can be attested by Akrians who lived that stage and experienced its ugliness:

The main road on which the regular bus service is provided to run from Akria to “Godaif” through “Idaga Arbi” and the center of the city, was a well-paved asphalt road with beautiful trees adorning both of its sides for the whole of its length excluding the last couple of Kilometers which entirely extend inside Akria. Unlike the section extending from the beginning of Idaga Arbi to Godaif, the section in Akria was a dusty dirt road with no asphalt pavement or trees adorning both sides of the street. This is not because the municipality lacked the budget to fund asphalt paving the lesser length of the bus route in Akria, nor was it meagerness of treasury for planting trees along both of its sides as was the case in the longer section of the road. The reason, in fact, was that the authorities were convinced that the neighborhood of Akria was and remained a strong source of the national movement and at the forefront of the opposition to the imperial-occupation government since its first day. This justified, in the eyes of the municipal authorities, the cutting of the provision of services to the minimum for the residents of the neighborhood, and the imposition of unfair taxes in the neighborhood on real estate against non-existent services as a kind of collective punishment.

Years of petitions, appeals, and complaints, by the residents didn’t bear fruit, and when, at last, it did, it was a sour fruit! The municipality decided to adorn the main road by planting Cactus (ቆልቃል) on both of its sides and there was no mention of asphalt-paving. This didn’t sit well with the residents of Akria because cactus beside its being thorny and unfriendly was also thought of as attracting to snakes and other reptiles, I don’t know if it is true but that was what they thought. There were also some who understood that by planting cactus on their street and not ordinary trees as the longer section of the same street was enjoying, the city authorities were, probably, sending an obscene message to the inhabitants of Akria. It may be, they thought, that the city authorities were telling the residents “ቆልቃል ይእ**ም”. And even if the city authorities were innocent and didn’t intend to say the obscene phrase, seeing the cactus plant, day in and day out, the Akrian will hear it said loudly and repeatedly by the plant itself, and as such it seemed that the cactus plant in Akria was challenging and calling for a response.

One morning, only weeks after planting the provocation, the small wild thorny trees (Cactus) where knocked down during the night and uprooted all left lying on the side along the road where they were challengingly standing and affronting the residents of Akria for few days. The police and the city went crazy, sniffing everywhere to trace those who have done the deed. It was to no avail, but every man, woman, and child in the neighborhood knew who has done it, and by the names too.

Revolutionary Youth

A rebellious neighborhood is what it is courtesy of its inhabitants, and in the case of Akria there was no shortage of rebellious individuals and individual families. One remembers a young Akria boy, Abdulhamid Dawood, who joined the revolutionary army of the ELF and was martyred in the early days of the revolution. Sheikh Said Derenkai, an elderly Akria man, was a preferred target of imprisonment by the Ethiopian occupation forces until he joined the Revolution at the late age of 65 years, Abdulkader nicknamed Carpenter who joined the Eritrean Liberation Army (ELA) after getting a master’s degree in economics from a polish University and was martyred only two weeks after his joining the (ELA), there was also Said Bashir who was publicly hanged in Idaga Hamus on the order of an Ethiopian court. It would be a long list to enumerate those from Akria who joined the fighting for independence neither it is easy to enumerate those who paid the supreme price. Almost every house has a martyr and martyrdom didn’t stop and continued starting before the federation, Imperial Ethiopia, the Derg terrorism, to the worst of them all- present order of the PFDJ. But the story of Amin and his mother is the real interesting story as it reveals the burden that wars put on the shoulders of ordinary innocent people, as the case is with all wars:

The Mother

From the day he was born and until the early teens of his age he lived an easy life under his financially stable grandfather’s roofs. His father, long since disappeared when he was just a toddler never to be heard of again.

After the death of his grandfather, his mother traveled to Saudi Arabia to work when he was sixteen or seventeen. Two or three years later he, also, migrated to Egypt to join a vocational secondary school where he was to be trained in mechanics. This seemed to have worked within his view of himself in the years ahead as his dream was to transform his passion for machines to a livelihood and career after few short years of training. But things didn’t work out all the way to his targeted objective, for after finishing the first of the three-year course necessary to get certified, he was somehow recruited in the PLF ( a precursor of EPLF) ranks and was sent to Syria for training. He completed his training and was sent to Eritrea to join the fighters of the PLF after which nothing was to be heard of him for a long time. Suddenly, one morning his pictures were in all Egyptian Newspapers as one of four hijackers of a western company airliner which was redirected from Europe to Cairo from its original destination. After evacuating the airplane of its passengers, the hijackers set it ablaze using bombs and other incendiaries. The perpetrators, in the end, surrendered themselves to authorities and Amin and his friends served less than a year in the Egyptian jail, perhaps this is so because the operation served the Egyptian policy of the time, especially that the hijacking operation took place only a short time before the 1973 war.

Although the operation was carried out in the name of a leftist Palestinian organization, friendly with the Eritrean PLF, consequently, it is difficult to argue with such claims, as that which claims ‘connivance’ of that Eritrean organization in this operation. There is no solid evidence that the Eritrean organization was involved in this operation, but a question which would be answered beforehand remains unanswered… was it possible for an active member of the Eritrean organization and a member of its fighting force to leave his unit and take part in a hijacking operation in faraway lands and then return back and rejoin the ranks of his organization’s fighting force?. It is also of little doubt that the Egyptian intelligence may have been, somehow, behind the operation at some level, for how could it be possible that such an operation which took place in the Egyptian soil, went unpunished except for a few months behind bars for the perpetrators, hardly a punishment even for a minor offence! Amin returned to his fighting friends in Eritrea and served in the PLF beyond its transformation to the EPLF. He lost his life in the botched adventure of the first battle for Massawa. But that is not the most interesting part of Amin’s story; his story didn’t die with his death, it continued even after his martyrdom in Massawa. His mother was told of his death and martyrdom but she offensively denied the news and made it clear that she needs no condolences nor that she should be bound by any behavior or dressing code as society may dictate for a certain period, tokens of sorrow and grief; to some she told that her son didn’t die and that it all was a miserable lie. She didn’t interrupt her normal life, and People saw this as something besides abnormality. Others, perhaps the majority, thought that the woman has gone mad. She showed no grief or even shed a tear for the dear departed and continued in such a condition for years until everybody thought that Amin was forgotten. When in the end of her life, after the independence, a lifetime-friend of Amin visited her, she was sounding well, her looks graceful, and her mood mirthful and welcoming. She was so relaxed as much as reminding her guest of some old events and stories involving him and Amin in the old good days. At the end of the visit as they were shaking hands and saying goodbye she ceased his arm forcefully clenched it tightly and saying” You don’t think like the others, do you? Do you believe I am a mad woman and that I don’t perceive the heavy loss that has befallen on my head, that I have lost Amin forever? He didn’t know what to say, then she continued saying: “But these are concerns of mine anyhow! No one can do the other’s not even his sorrows!. Go now God bless you; don’t think about what I said! Forget it forever. Go now!

She died not long after that meeting, and I kept, at times, thinking about my friend’s story and her last words and what she meant by them until one day I was told that before the meeting mentioned above, a close relative of hers died in Jeddah Saudi Arabia, and she had to visit and give condolences, and as tradition dictates she may had to wail (መልቀስ), the people who were present and took notice of what she was saying wondered of what they have seen and heard, she was weeping and saying in a low toned voice “ oh, I had a message for you to take with…I had a message for you to take with! ”, And kept repeating it like a broken record.

The conclusion was clear. It was clear to me that she was most unhappy women; she was disappointed and crashed by her son’s destiny. He was her only son, and now she is trying to throw an absolute privacy on what concerns his demise, to her it is so private to an extent that no public grief or expression of sorrow is to mitigate the pain. She wished also if she could have sent a message…a message? That even is closed to her and impossible! One can’t send a message to be taken with a dying man unless one is sure the messenger accepts his death before his death and will die immediately after the message is handed to him! You can’t tell a dying man to take a message to the world of the death! What a cruelty would that be.!

To whom would the message be sent if not to her only son? I have read in the past something similar to this story, strikingly similar in a way, and I remember it every time the story of Amin and his mother is reiterated. This is what I read; I am copying here a snippet from the essay-on sorrow- by the French essayist Montaigne:

“the story says that Psammenitus, King of Egypt, being defeated and taken prisoner by Cambyses, King of Persia, seeing his own daughter pass by him as prisoner, and in a wretched habit, with a bucket to draw water, though his friends about him were so concerned as to break out into tears and lamentations, yet he himself remained unmoved, without uttering a word, his eyes fixed upon the ground; and seeing, moreover, his son immediately after led to execution, still maintained the same countenance; till spying at last one of his domestic and familiar friends dragged away amongst the captives, he fell to tearing his hair and beating his breast, with all the other extravagances of extreme sorrow. The story proceeds to tell us that Cambyses asking Psammenitus, “Why, not being moved at the calamity of his son and daughter, he should with so great impatience bear the misfortune of his friend?” “It is,” answered he, “because only this last affliction was to be manifested by tears, the two first far exceeding all manner of expression.”

Revolutionary Siblings

Although this essay is, by all measures, incomplete it would even be more so if it closed itself without mentioning two great men of Akria. These were the two brothers, Musa Mohammed Nur and his younger brother Dr. Taha Mohammed Nur.

When Taha was studying Law in Cairo, his brother Musa (now Hajji Musa) back in Asmara, was deeply immersed in the struggle for Eritrea, some of his contributions are known to the public, Wolde Ammer, a veteran ELF figure, mentioned him few times in his writings the last of which was in the context of remembering Siyum Harestai in his 12th year since his martyrdom.

Ustaz Ali Mohammed Saleh Shum, a veteran of the war for independence, wrote an excellent book regarding his experience with ELF as a fedayyin during the long war for Independence. In page 39 he tells the story of a commando operation in Asmara Airport in June 1963. The objective was destroying the aircraft on the ground of the airport as a first step and then destroying the power generator in “SEDAO” as the next one. The Airport operation succeeded while the SEDAO operation failed. The two who executed the operation were: Said Hussein and Mohammed Haroon. Their hiding place before and after the operation was the house of Musa Mohammed Nur in an Acria “via Otto Street”. The author, Ali Mohammed Salih Shum, was himself a practiced commando element of the ELF, contributed to Mahber Shaw’ate as an active member, and contributed to the Eritrean Struggle under the EPLF. In the page 30 of his book “ Memoirs of an Eritrean fighter” he tells about Musa Muhammed Nour as being an important city element of the ELF’s, and that in the aftermath of the Airport Operation he was thrown to jail for close to two years on the account of giving support and refuge to the ELF commando unit. He further tells the readers that Musa was exposed to long and cruel torture sessions but that he was steadfast in his initial claim that his relationship with the commando unit was a relation of the landlord to the tenant. The book, however, forgot to tell that Hajji Musa was thrown to prison once more in the Derg era. I don’t have to go through what happened to Hajji Musa in the present, under the EPLF/PFDJ regime. I will only say that in broad daylight, without due process of the law a man of ninety-two years old was thrown to jail and without due process of the law! This frail old man must be very strong to put him in incarceration! What a shame!

Dr. Taha Mohammed Nur was not different from his brother when it comes to dedication in the national effort for independence. Again Ustaz Ali Mohammed Saleh Shum remembers Taha (page 21) and remembers how he was elected a member of the founding committee of the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) in August 1960, in Cairo while he was a student. He also served as a representative of the PLF in Cairo in the early seventies and was active in helping Eritrean Students in getting scholarships in the Egyptian educational institutions. After the independence, he was appointed a member of the committee for writing the ill-fated Eritrean Constitution. Dr. Taha died (others say murdered) in one of the prisons of the Eritrean regime where he was thrown for no apparent reason; he was not accused of any wrongdoing!

As I was coming to close my essay News of the death of Hajji Musa were Brocken, Hajji Muse gave the ultimate price. He was destined to wards that all his life. May Allah accept him between the truthful, the martyrs and the Salihin.

Awate Forum