What Memory Chooses, and What It Omits

Of Trains, Turkays, and Tongues:

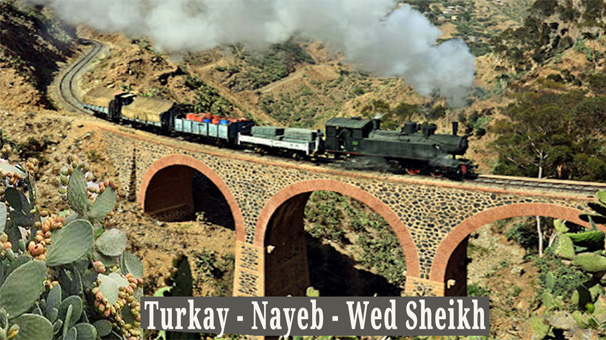

Let’s begin with the train. That lumbering, iron-tongued beast that cut through the Horn like an artery forced onto a map. No, Wedi Sheikh didn’t design it. He didn’t pour steel or survey colonial blueprints. But what he did and what so many like him have done across time is sing the thing into meaning. That’s what poets do when history hands them an uninvited inheritance.

So yes, let’s be clear: the singer did not build the train. But he built the memory. And that, my fellow wanderers, lasts longer than any set of rails.

Yet here comes an interlocutor, arms crossed, demanding receipts.

“How can you praise the song of the train when it was the colonizer’s machine? “What about the Turkays and the Shawshis and the Naiebs? The Ottomans married our women! Why is no one outraged about that?”

Ah. Here we are: a classic game of “whataboutism,” brought to you by the whirlpool of false equivalences”.

Let’s address this with the grace of a café debate and the sharpness of a broken qalet teacup.

But before we proceed, let’s remember something about discourse itself: One is monologue. Two are dialects. Three turns into a symposium. And we’ve earned ourselves a symposium today.

The Myth of Native Trains

Let’s dispense with the fantasy that the railway was ever for “us.” The tracks didn’t ask for local passports. They were drawn to extract, not to unite. The train, like so many colonial gifts—cricket, census, courthouse—was nothing more than a Trojan horse with a steam engine.

But here’s the miracle: we made it ours anyway. We waited for it, cursed its lateness, and measured love by its departures and returns. And Wedi Sheikh, standing somewhere between nostalgia and satire, captured that transformation in melody. To reduce his song to an engineering oversight is like faulting Mahmoud Darwish for not laying the bricks of a demolished home.

Celebrating the song about the train is not a celebration of the colonial project that introduced it. It is a celebration of what we, the people, made of that imposition: subvert it. Appropriate it. Problematize it. And own it, too. How we turned an engine of the empire into a vessel for longing, reunion, and resistance. This is what scholars like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o mean when they speak of reclaiming the means of memory production.

The Turkays and the Selective Silence

Now to the Turkays. The Shawshis. And the Nayebs. Yes, let’s talk about them.

Ottoman and Egyptian administrators didn’t just leave behind architecture. They left names, lineages, and social rankings. That some descendants still carry these names like honorary badges is a truth worth unraveling. That some look down on Beni Amir as “less civilized” is not only shameful but colonial mimicry at its finest. Fanon could have published a sequel on that phenomenon: The Colonized Who Colonized Back.

But here’s where the argument gets sneaky: It suggests that unless we’re simultaneously critiquing every historical injustice, we must keep quiet about the British and the French. That’s like saying you can’t protest police brutality unless you also denounce your neighbor’s bad parenting.

Critique is not a buffet. It’s a kitchen. Everything simmers together, but you don’t serve it all on the same plate.

Moreover, internal hierarchies among the Turkays and Shawshis deserve interrogation not to distract from European colonial critique, but to expand it. To say, “Why criticize the British if we don’t critique the Ottomans?” is like asking why speak of slavery if we haven’t resolved classism. We must do both.

So yes, let’s debate the Turkays. But don’t wield that silence as a shield against confronting the empire. Rather, let it stretch the frame wider.

Of Memory and Its Editors

What gets remembered? And what gets the “pass”?

European colonialism is critiqued more loudly not because it was uniquely evil, but because it left a paper trail. It was obsessed with its own bureaucracy. Ottoman misdeeds are harder to quote, not because they were innocent, but because they were often oral, invisible to the European gaze, and therefore easier to domesticate.

And let’s not pretend every family wanted to excavate its Ottoman skeletons. Some preferred the myth of noble ancestry to the messier truth of military intermarriage, class elevation, or betrayal.

So yes, memory omits. Not out of malice, but out of architecture. What’s built gets archived. What’s sung gets remembered. What’s whispered gets forgotten until someone asks the right question at the wrong time.

On Language as the Empire’s Shadow

A friend asked me to elaborate on a line I wrote elsewhere: “Colonialism had taught Eritreans to measure progress in Italian and to fear one another in English.”

That’s a fair question: isn’t language, like culture, something that evolves? Isn’t English now the vehicle of science, diplomacy, and digital exchange? Why drag its origins through the colonial mud?

I don’t object to English. I object to how it was handed down. Italian was not chosen; it was mandated. English was not offered; it was enforced. These languages arrived not as gifts, but as gradients of power. In a multilingual land, speaking English became the mark of access. Speaking only Tigre or Saho became the mark of marginality.

To speak Italian was to be “progressive.” To speak English was to be “governable.” To speak only local tongues was to be forgotten.

Language in the colonial context is never neutral. It is currency. It is a sorting mechanism. It is how empires rank their subjects without lifting a rifle. And when the colonized begin to rank themselves in that same tongue, the empire no longer needs a governor – mimicry becomes its own whip.

So no, I don’t grieve for the language. I grieve the silence it imposed.

In Conclusion: We Remember Through Song, Not Steel

We don’t celebrate the train. We celebrate that we survived the train. That we made it a thing of longing instead of subjugation.

We don’t forget the Turkays. But we don’t weaponize their omission to absolve the empire that taught them to see their cousins as inferior.

We don’t fear English. But we remember the wound beneath its grammar.

And we certainly don’t pretend that memory is neutral. It is a curated exhibition, with exhibits constantly being rearranged.

“Bitgooli la,” the singer says.

“You tell me no,” a la Abdel Aziz El Mubarak.

But the people said yes to remembering on their own terms.

So let the train whistle in the distance.

Let the names echo across generations.

Let us debate them all: Turkay and train, Shawish and song. English and erasure until memory becomes not a battleground but a gathering place.

Where everyone is accountable.

And no one escapes the ledger.

Awate Forum