Schooling and Social Capital Among Eritrean Refugees

Revolutionary Schooling and Social Capital Among Eritrean Refugees in Sudan

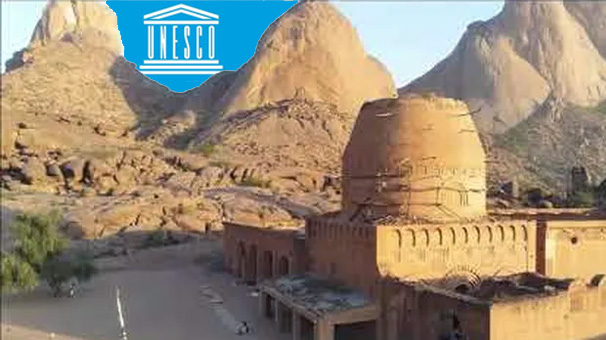

A remarkable educational experiment took root in the arid borderlands of Kassala, Sudan, in the shadow of Eritrea’s long and bitter struggle for independence. In 1977, the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), in collaboration with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Sudanese Ministry of Education, established a school that did more than teach—it transformed. Primarily operated by Eritrean freedom fighters who doubled as educators, the school offered structured, stipend-supported education to refugee youth. Its curriculum was purely academic. But by virtue of the background of its teachers and students, political consciousness, national identity, and practical service became part of it. It was a space where the displaced did not merely survive; they prepared to lead.

As a former student at the Kassala school, I witnessed firsthand how this unlikely institution became both a sanctuary and a seedbed for revolutionary dreams. Ours was not merely a cohort of learners but a community in exile, bound by purpose and resilience.

These students, many of whom were exiled, orphaned, or separated from their families due to war, were not simply recipients of charity. The educational model adopted by the ELF and supported by the UNHCR was rooted in the philosophy that education in exile could be an asset. The students received modest stipends to support their studies, which served as financial assistance and a gesture of recognition and dignity. The stipend affirmed that education was labor and that the youth were an essential part of the nation-in-the-making. One of the school’s most enduring legacies was its role as a site of social cohesion and capital among a displaced but remarkably diverse student population. In any classroom during the late 1970s and early 1980s, students from Asmara, Keren, Massawa, Barentu, and Nakfa—urban and rural, Muslim, Christian, highland, and lowland—came together in shared classrooms. The shared educational experience created a rare space for dialogue and solidarity across Eritrea’s regional, linguistic, and class differences. Friendships forged in Kassala classrooms later became the foundations of transnational networks of Eritrean professionals, activists, and educators. The school was not only preparing students for exams or armed struggle but quietly binding together a fragmented nation in exile.

The school in Kassala was staffed by a cadre of freedom fighters who had traded their rifles for chalk. Those teacher-combatants imbued the curriculum with a sense of urgency and purpose. Standard academic subjects were taught, but interwoven with themes of resistance, self-determination, and national history. The students learned under conditions far from ideal, but the collective sense of purpose bridged the gap between resource scarcity and intellectual richness.

What set this educational model apart was its integration of theory and practice. Upon completing high school, students could spend their summer months within the liberated zones of Eritrea, living and working among the ELF’s fighting forces.

This civic service was a symbolic and practical rite of passage. It allowed young people to witness firsthand the conditions of their occupied homeland and the daily realities of the armed struggle. It also reinforced the idea that intellectual growth and national liberation were inseparable.

This blend of education and civic engagement forged a generation that would carry the scars, knowledge, and dreams of a nation in exile. Many of these students eventually migrated to Europe, North America, and the Middle East, becoming professionals—engineers, doctors, academics, and community leaders. Their contributions abroad were deeply rooted in their transformative schooling in Kassala, which went beyond textbooks to shape consciousness, discipline, and commitment.

The story of Revolutionary School in Kassala is a testament to what refugee education can achieve when guided by vision, sacrifice, and the belief that displaced people are not merely victims but active agents of their futures. It challenges humanitarian models that view refugees only in terms of need and instead presents a paradigm of dignity, resistance, and reconstruction.

In an era where refugee education remains underfunded and often depoliticized, the Kassala school offered a powerful counterexample. It illustrates the potential of refugee-led education to nurture leadership, preserve identity, and build transnational legacies. As more histories of displacement and exile are recovered and documented, the contributions of institutions like this school must be acknowledged and preserved. Their legacy is not just Eritrean or Sudanese—it is a universal story of what it means to learn.

Awate Forum