Editor’s note: the byline data is corrupted; so far we couldn’t resolve the technical problem. The writer of this article is Semere Andom (iSem).

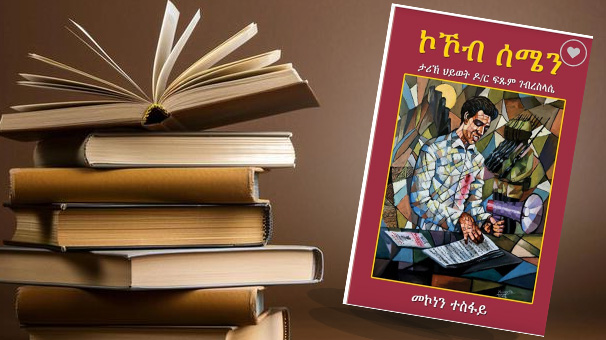

Last week, I had the privilege of joining a group of friends to read and reflect on Mekonen Tesfay’s book The North Star: The Biography of Dr. Fitsum. Here is the reflection I shared with these avid readers and writers.

The North Star by Mekonen Tesfay is a familiar and heart-wrenching Eritrean story—one of broken dreams and aspirations cut short by the long struggle for independence and freedom. It speaks to the unfulfilled dreams of a nation, a family, and an individual.

A family sacrifices everything to educate its children. The children excel and make the most of the limited opportunities available to climb the academic ladder—a path toward professional success and, by extension, family happiness. ዓዲ ክኾኑ They promise to help their family, to ease their burdens, and to repay them for their toil so their parents can finally relax. Children are the RRSPs and 401(k) sunset days. Then in the end, the revolution consumes them. Devours them.

Through vivid anecdotes and intimate testimonials from the Ghedli generation of freedom fighters, the book attempts to connect the dots surrounding the mysterious death of Dr. Fitsum G. Sillasse—fifty years later. It is a bold and daunting journey, made more so by the fact that the prime suspect in his death is still alive—and a general, no less.

The letters Dr. Fitsum wrote to his loved ones—first from Addis and later from Europe—are endearing and intimate, filled with love, dreams, and contradictions. His authentic Tigrigna expressions and highland mannerisms leap from the page, as does his sense of humor, especially when he playfully teases his siblings, nephews, and nieces with nicknames, asks after relatives, and addresses them as “Ayay” and “Sanday.” His humor reflects the spirit of his generation and culture. One memorable line captures this perfectly: “Please tell my dear mother to find me a fiancée; otherwise, when I return, I will bring her ጸያቂት መስርዕ.”

The author, however, offers no insight into his own positionality—who he is, his relationship to Dr. Fitsum, what sparked his interest in writing this book, or his desire to place it within the annals of Eritrean history. There is no “right” or “wrong” positionality, yet understanding an author’s perspective, motivations, and interests behind such a monumental task is crucial in social science work, especially when addressing a controversial historical event like the case of Dr. Fitsum. Without this context, readers cannot fully account for the inevitable biases that shape human interpretation and recollection, no matter how well-intentioned, when forming their own conclusions.

The Distraction from the Main Story

The author devotes some eight pages to Adey Manna, Dr. Fitsum’s larger-than-life and beloved mother, painstakingly and sagaciously detailing her character, humor, generosity, stature as a strong and independent woman, and even her lineage. Here knack for conflict resolution is well articulated. At times, the reader almost forgets that this book is about Dr. Fitsum, and it is unclear how relevant these details are to his biography. The author falls into a similar trap when detailing Dr. Fitsum’s genealogy on his father’s side. Both reminiscent of biblical-style lineages: so-and-so begot so-and-so…

Furthermore, through omission, the book portrays Dr. Fitsum as a flawless and selfless individual. There is no mention of failed endeavors or conflicts with friends— almost every testimonial, every recollection borders on canonization. Some accounts even suggested if he were alive, he would have been a uniquely exceptional, just Eritrean leader. This, of course, is not Mekonen’s fault, as he merely reports what he was told. But how can these Cassandras know that Dr. Fitsum would not have changed? There is no mention of arguments or falling-outs with friends or comrades. As the protagonist in this creative nonfiction book, Dr. Fitsum is portrayed as likable but flawless.

And speaking of biblical-style genealogy that Mekonen penned, even the Son of God, according to the Bible, lost his temper when merchants turned his father’s house into a marketplace.

The Irony

In his letters, Dr. Fitsum assured and reassured his family that he was going to Yugoslavia but always insisted, “I will never be Yugoslavian.” Yet, he became one when he fathered a child with a Yugoslavian woman—a deeply relatable feeling of exile.

The book, on many occasions, tells more than it needs to. For example, in Germany, when Dr. Fitsum and his friends enter a bar, the waitress stares at him, and the reader immediately assumes it is attraction, since we have been told that Dr. Fitsum was tall, handsome, and had curly hair with ኩመላይ complexion. But later, when the waitress orders him to leave, we realize it was not about love after all. However, the author goes on to explicitly explain that it was not love—something the reader has already understood

without needing to be told.

On Language

The writer’s voice vacillates between traditional Tigrinya and literal translations from English, and at times he seasons his prose with Ghedli diction.

Literalism:

For example, he writes, “Behind a successful man there is a successful man.” In Tigrinya, there is no “successful woman” behind a successful man—rather, there is always a woman ኣብ ጎኑ.

Author Mekonen also doubles down on literalism when he writes: “ዘይተዘመረሎም/ዘይተዘመረለን ጀጋኑ” In Tigrinya, ንጀጋኑ ኣይዝመረለንን፤ ይድረፈለን አምበር ወይ ድማ ይዋጠየለን/ይዋጠየሎም.

ሃንስ ወድ ዘሞ አንታይ ም አንታይ ወዲ አልፉ ኣብ ምንታይ ኔሪ ማህረምቱ ጽልማ ትመጻክም ኣላ ሓብቲ ለማ. Th

Unadulterated Gold:

At times, however, the author wields pure, traditional linguistic gold. For example, he writes, “This story is narrated (ተጽጸውዩ ) on this page. And he graces us with an even higher-carat Tigrinya expression when describing Zewdi and Dr. Fitsum as መትሎ መታሉ.

Conclusion

This is a commendable and monumental endeavor that Mekonen Tesfay has undertaken, a project that those who were gushing about Dr. Fitsum could have themselves pursued. Despite the importance of the subject, this book is, as far as I know, the first serious attempt to write about Dr. Fitsum. The discrepancy about the exact year of his death is also telling, revealing the ELF’s mishandling of the incident.

Moreover, the author did not reach out to Abrahaley Kifle, the man who many suspected in the murder of Dr. Fitsum, for an opportunity to tell his side of the story. Whether Abrahaley would have agreed to speak or not is another matter. Yet, after the book was published, Abrahaley appeared in a series of YouTube interviews—with this very book placed on the table during the first episode.

One particularly moving anecdote in the book recounts that when word came that Dr. Fitsum had fathered a child, the upper echelons of the ELF such as Tesfay Degiga were so elated that they reported, “Dr. Fitsum ሓድጊ ገዲፍልና”.

Although North Star is about Dr. Fitsum’s life, contributions, and the circumstances surrounding his death. Yet it is also a story painfully familiar to almost every Eritrean family. Palpable. I hope this book serves as a stepping stone to ensure that the stories of others who have met the same fate as Dr. Fitsum—and they are many—are also remembered. I further hope this work will be supplemented by more rigorous research to indelibly document and trace the countless heroes who have perished at the hands of their own brethren.

Awate Forum